Michigan tried to limit 'barbaric' practice in 2016. Educators used it 94,000 times since.

The story was originally published in Detroit Free Press with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism's 2022 National Fellowship.

GETTY IMAGES

Kai Atallah can’t forget the bright lights.

The 9-year-old from west Michigan isn’t talking about the sun streaming through a classroom window. Not the shine of a bottle rocket zooming into the sky as he watches with his Cub Scout troop, or the spotlight spinning from the fedora worn by Inspector Gadget, one of his favorite television characters.

He’s referring to the harsh barbs of overhead fluorescent bulbs that are etched into his memory, shining down onto the white concrete walls and firm carpet of a room he could not escape.

“You’re trapped, and alone, in a room and you can’t get out. And you just get more and more frustrated and more and more angry and more and more upset,” Kai said, his words coming rapidly.

Kai Atallah identifies plants with an app during a field trip to a local park Friday, Sept. 9, 2022, in Holland. CODY SCANLAN/HOLLAND SENTINEL

“I kicked the door, pounded on the door. Yelled.”

Kai is one of thousands of Michigan schoolchildren subjected in the last five academic years to practices meant only for emergencies: seclusion and restraint.

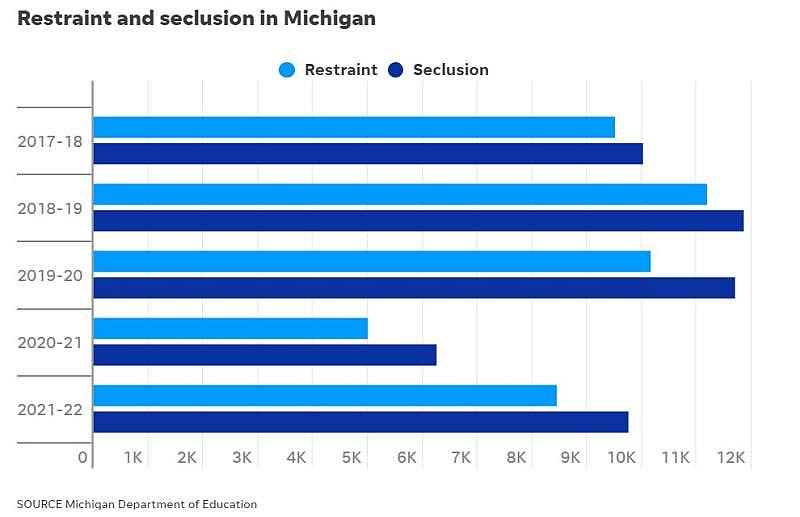

While Michigan lawmakers tried to ban the tactics in 2016, a Free Press investigation found educators across the state secluded or restrained students nearly 94,000 times in the last five school years. The state began collecting data in the 2017-18 school year following the passage of new laws.

That means on average, more than 100 times a day, Michigan educators used what experts say are psychologically damaging practices on children. Considering most schools limited or canceled in-person classes for weeks or months due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the daily usage of both seclusion and restraint are likely much higher.

Our most vulnerable children

More than 2,000 students were secluded or restrained in public schools every year with the exception of 2020-21, when many students attended class remotely due to the pandemic. Like Kai, 4 out of 5 have disabilities.

Kai Atallah swings as he listens to his mom, Cassie Atallah, read to him during his homeschool lesson Friday, Sept. 9, 2022. Kai, an autistic child, has been homeschooled for more than two years after the use of restraint and seclusion in the classroom. CODY SCANLAN/HOLLAND SENTINEL

Of 1.4 million students in Michigan schools, 194,514 have disabilities.

Seclusion frequently involves adults forcing young children into a small, padded room and leaving them inside for a minute or sometimes as long as two hours. Restraint entails adults physically limiting a student’s movement using force.

Substantial scientific research published over decades shows the potentially harmful impact of secluding and restraining children, especially those with disabilities. An expert who spoke with the Free Press said there are no scenarios where seclusion is appropriate, arguing the practice creates trauma that can compound the behavioral problems educators used to justify seclusion.

Kai was 5 when diagnosed with autism during the spring of his Kindergarten year. Seclusion and restraint soon became a part of his daily school routine.

His school, Black River Public School in Holland, didn’t report to the state how often Kai was forced into what they called the “time away room” or the “reset room.” But Kai’s mother, Cassie, kept track: During one six-month period in first grade, she says school officials informed her Kai was secluded 93 times, sometimes in a seclusion room or sometimes in a conference room.

Cassie and her husband, Daniel, said they believe the educators who made the choice to restrain or seclude Kai are largely dedicated professionals trying their best. But the parents feel the school failed Kai, and his educators'decisions still have a devastating impact on him and his family.

“It’s been deeply, deeply, deeply painful for me. … I had to quit my job to keep my son safe,” said Cassie, a former art teacher at a Michigan public school.

“I haven’t been able to have play dates in the same way as other people have. He’s not invited to birthday parties the way other people are. …This has been my entire identity for years. I haven’t been able to work. I haven’t been able to experience life the way other parents do and it’s very draining.”

The nearly 94,000 instances of seclusion and restraint recorded by the state likely undercounts how often the tactics are used in Michigan schools, according to a Free Press analysis.

That’s because the elected officials who sought to ban these practices six years ago did not include ramifications for not following the law. There are no penalties, for instance, for the improper use of seclusion and restraint or for failing to report accurate numbers to the state.

Michigan Lt. Gov. Brian Calley speaks about the rights of people with mental disabilities Tuesday, Dec. 20, 2016 at the Macomb Oakland Regional Center. Next to him are David Taylor, left, a community advocate, and The Arc Michigan Director of Public Policy Dohn Hoyle. ROBERT ALLEN, DETROIT FREE PRESS

Former Lt. Gov. Brian Calley in the past described the practices as “inhumane” and “barbaric.” The mid-Michigan Republican was the architect of the 2016 legislative package while he was in office with then-Gov. Rick Snyder. In a recent interview, Calley said the only way he could get enough votes was to ensure the bills explicitly excluded consequences for breaking the law.

“Of all my time in office, and all the initiatives that I worked on, the degree of difficulty in getting a ban on seclusion and restraint practices in schools is perhaps the most discouraging,” said Calley, now president of the Small Business Association of Michigan.

“What I was unable to accomplish was a real penalty for noncompliance. That was the line in the sand. I couldn’t get the bill passed if it had penalties for noncompliance. I very much consider that unfinished business.”

The Free Press found multiple instances where educators violated the letter or spirit of the law. Among them:

∎ Districts are not supposed to seclude elementary school kids for longer than 15 minutes and kids in middle and high school for longer than 20 minutes unless there’s an emergency. We identified multiple cases where children were secluded for more than an hour.

∎ We found at least two districts that reported zero acts of seclusion and restraint to the state – but were later exposed for using those tactics. Calley believes other districts reporting zero have likely evaded the state reporting requirements.

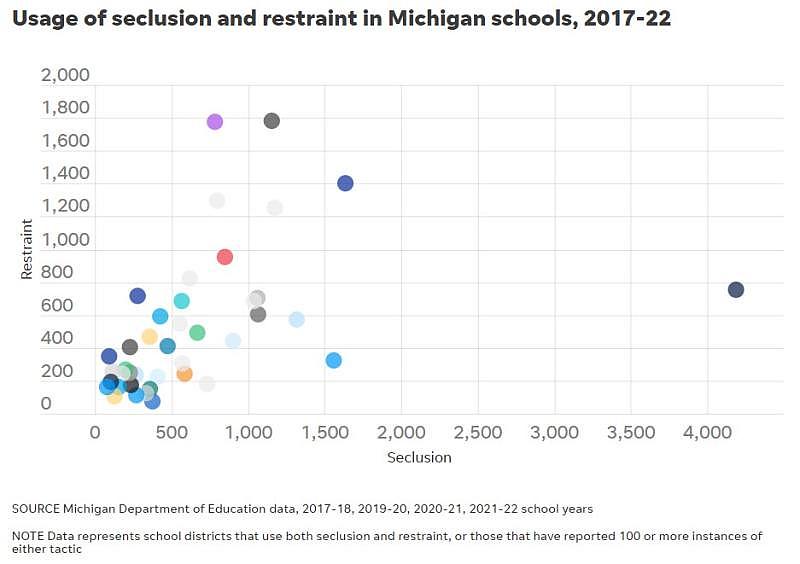

∎ Districts are supposed to analyze the data they collect in an effort to find ways to reduce how often they use seclusion and restraint. We asked the 15 districts that reported using these tactics the most for any analysis they had conducted – only one provided any written documentation beyond the numbers reported to the Michigan Department of Education. Two others asked for $3,198.75 and $176.40 for documents. The Free Press declined to pay those fees, arguing the records are public and should be released for free or nominal costs.

A state Education Department spokesman wrote in an email that the department had no power to enforce seclusion and restraint laws, or to check in with districts about why they were using either tactic tens of thousands of times.

Despite state inactivity, federal investigators have taken some action. The U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights is investigating eight Michigan school districts for their use of seclusion and restraint.

Earlier this year, Huron Valley Schools in Oakland County in order to resolve a federal investigation agreed to improve how it uses seclusion and restraint. The department declined to say whether the district is actually living up to its end of the bargain.

Federal inquiries are slow; some have dragged on for more than seven years. All the while, many of Michigan’s most vulnerable students are isolated in dark rooms or pinned down by adults who have deemed various behaviors as emergencies, according to limited records obtained by the Free Press. Examples of reported behavioral emergencies range from children fleeing adults and flipping chairs to hugging a peer too tightly and ripping up paper.

The law defines a behavioral emergency as “a situation in which a pupil's behavior poses imminent risk to the safety of the individual pupil or to the safety of others.” Seclusion and restraint may be used only as “a last resort emergency safety intervention,” according to the law.

In a 2019 incident in Huron Valley Schools, a student was secluded for 13 minutes after reportedly losing a game of Connect Four and also threatening to stab an adult with a thumbtack. In another from the same school district, a student was restrained for four minutes after an argument with a peer over reindeer prompted an outburst that included throwing objects and spitting.

In Kai’s case, the boy on occasion threw classroom materials and kicked them. In other times, he hit staff. Another time, during an emotional meltdown, records show Kai marked up another student’s arm with scissors.

“He was doing things that were threatening to safety. But at the same time you think, no one was really in danger,” Cassie said, noting that Kai was 5 years old at the time, her 3-foot-tall “little guy.”

Initially, his parents weren’t sure what was happening or what they should do. Kai would come home after spending minutes – but occasionally much longer, according to his mother – restrained or tucked away in a tiny room and not tell his mom and dad anything.

Cassie Atallah speaks on the negative impact the use of restraint and seclusion had on her son.

DETROIT FREE PRESS

“I wouldn’t, to be honest,” Kai said, when asked what he said to his parents about being secluded.

“Because it was too bad to talk about.”

When Cassie and Daniel pulled Kai out of school in 2020, Cassie took on the role of homeschooling Kai full-time. He’s made substantial emotional progress since then, thanks in part to therapy and medication.

But it’s a process that required a fair amount of privilege, time and money. Those resources may not be available to other Michigan students restrained or secluded thousands of times since Kai left the public school system.

Cassie and Kai Atallah work to construct paper airplanes during a homeschool lesson at their home in Holland. Kai, who was diagnosed with autism, has been homeschooled for more than two years after experiencing the negative effects of restraint and seclusion while in school. CODY SCANLAN/HOLLAND SENTINEL

With time to reflect, Kai and his parents are talking now. They want to speak for the thousands of Michigan families who’ve endured comparable treatment and demand change.

“I’m going to put this as blunt as I can: Seclusion and restraint should be illegal. It’s wrong,” Kai said.

'Adults are supposed to keep me safe'

Seclusion and restraint are not unique to Michigan. For decades, educators across the country have used both practices in an effort to curtail behavior from challenging children.

Experts warned educators about the dangers of using excessive seclusion and restraint for decades as well.

A 2009 report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office found hundreds of allegations of death and abuse tied to children secluded and restrained in schools dating to 1990. Among the reported incidents: a 7-year-old who died after being held facedown for hours, children as young as 5 fastened to a chair with bungee cords and duct tape, and a 13-year-old who allegedly hanged himself in a seclusion room after “prolonged confinement.”

The report noted that while some experts thought seclusion and restraint techniques were useful, many determined they could result in death, physical injury or long-lasting psychological trauma, findings echoed in a 2014 U.S. Senate report.

“Use of either seclusion or restraints in nonemergency situations poses significant physical and psychological danger to students,” reads the introduction to the Senate report.

There are many ways to physically or emotionally hurt a child, especially one with a disability, by using restraint and seclusion, said Laura Strunk, a professor at Minnesota State University and a practicing school psychologist for a rural school district in Minnesota.

Strunk conducted a national study on the use of seclusion and restraint in schools. She said beyond the possible physical perils of broken bones and bruises, even the act of touching a child or forcing them into isolation can have drastic psychological consequences.

“Realistically, we have a lot of the kiddos that we work with who have disabilities do not want to be touched. They have sensory issues, they may have been harmed by other people, so they might have some trauma that they’ve experienced in the past regarding touch from other people,” Strunk said, explaining that kids may think: “Adults are supposed to keep me safe, so why are they locking me in this room all by myself? ”

Typically, she said adults who use seclusion or restraint argue they are keeping the school community safe, or that they’re intervening to ensure a student has the chance to successfully regroup.

But, she argued, the techniques are almost always unnecessary, and justifiable rarely.

“It should never be an option, honestly. We know it’s an option, but it really should never really be an option,” Strunk said.

Frequently, educators responding to the student’s behavior are expecting a small child to effectively regulate their emotions, a tall order even for many adults who don’t have behavioral or learning challenges.

“The agitation of the staff person just escalates the student, and then they feel like the student is out of control and so they need to restrain them. When in fact, if you go back and if you could record the scenario of something like that, you would actually see that it was probably the school staff who was out of control,” Strunk said.

Foundationally, she thinks using these practices comes down to a lack of trust between educator and child, and a lack of training. When students are agitated, trained educators can pick up on cues and address problems earlier to avoid restraint, she said.

Other reports arrived at similar conclusions. A 2019 expose from ProPublica found Illinois schools routinely used seclusion in violation of state law. But it also noted the federal government fails to properly collect data on how often either practice is used, highlighting the fact there’s no way to know whether districts are reporting accurate numbers.

Before and after the ProPublica series, federal lawmakers weighed creating a national standard to limit the usage of both tactics in schools. Repeatedly, they failed to act, leaving regulation up to states.

In 2016, Michigan lawmakers took action. The resulting legislative package created a system with an appearance of oversight, but in reality few avenues to determine whether vulnerable students are truly protected.

‘Sometimes they need to be treated like animals’

Back around that time, Calley walked up to a Republican colleague who he thought may be an ally.

Because both have children with autism, Calley, then the lieutenant governor, figured the state representative might share his criticism of secluding and restraining students with similar challenges as their children.

He was wrong.

“I said, ‘These kids are being treated like animals.’ And his response was, ‘Well, when kids act like animals, sometimes they need to be treated like animals,’ ” said Calley, who recounted the discussion in a recent interview.

“I really walked away from that interaction heartbroken about the callousness of the response.”

Problems with seclusion and restraint in the state go further back than 2016.

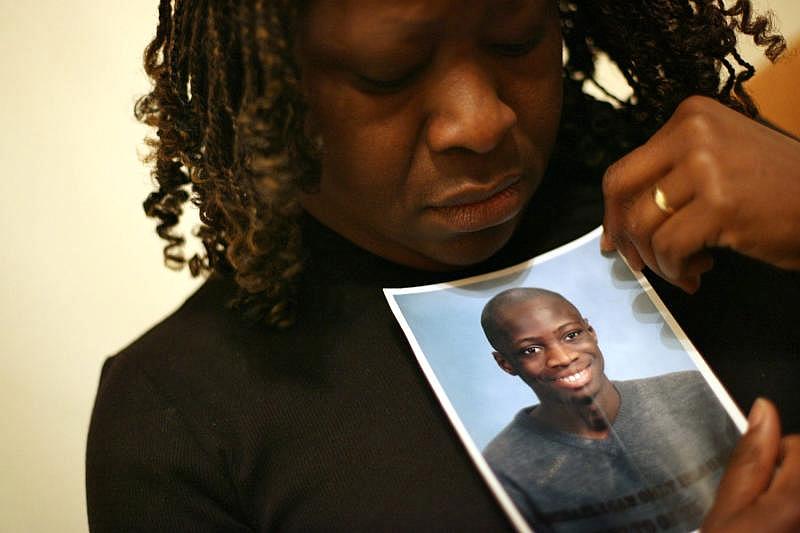

In 2003, a 15-year-old Kalamazoo-area boy diagnosed with autism suffered what appeared to be a seizure at Parchment High School, after which he started acting combative. Multiple adults forced him facedown to the ground, holding his arms and legs.

He died within a couple of hours. The boy’s mother settled a lawsuit against Parchment School District in 2006 for $1.3 million.

The same year, the Michigan State Board of Education enacted policies on secluding and restraining students. A decade later, some administrators, educators and lawmakers suggested schools followed the rules. But Calley and others received numerous troubling reports.

Elizabeth Johnson of Kalamazoo lost her son, Michael Renner-Lewis III, in 2003 when he was restrained at school. She has been lobbying with the Michigan Protection and Advocacy Services to make sure this does not happen to another child. Renner-Lewis, who had autism, died of prolonged restraint, after being held down by three people. (Photo: Kimberly P. Mitchell, Detroit Free Press) KIMBERLY P. MITCHELL, DETROIT FREE PRESS

It prompted Calley, working with then-state Rep. Frank Liberati, a Democrat from Allen Park, and others to introduce a package of bills. The measures banned all seclusion and restraint outside of emergency situations, defining what constituted an emergency. They required school districts to fill out reports every time an educator used seclusion or restraint and to notify parents as soon as possible. Districts were supposed to take that data, analyze it and use it to inform training and responses to challenging behavior.

The entire package aimed to “eliminate the use of seclusion and restraint,” according to the text of one bill.

There were few overt efforts to sink the bills, Calley remembers. The Michigan Education Association and the Michigan Association of School Boards publicly supported the final legislative package. But he said behind the scenes, there was a coordinated campaign to ensure educators could still use these practices and face few ramifications when they did.

He specifically remembered multiple interactions where, “every school seemed to have a story about some giant student with a disability that was dangerous and they were afraid of.

“It was almost like there was a conference somewhere and everybody said, ‘Say 6-(foot)-3!’ There’s this 6-(foot)-3 young man, and he’s 17 years old and he can overpower everybody,’ ” Calley said.

He specifically recalled an anecdote about a student being strapped to what was described to him as essentially a dolly in order to go by a school cafeteria, because the student exhibited problematic behavior while passing the lunchroom in the past.

“That type of practice is so outrageously unreasonable, that it really gave me a passion to … change the law so that it is banned,” Calley said.

“You can’t just do this in health care settings. Parents can’t just tie up their kids. The conclusion that I came to after reviewing the law is that the only place where nonemergency restraint and seclusion was legal was in schools.”

Advocates argued that without including reporting requirements in the law, it was impossible to know whether the use of seclusion and restraint was being abused. Opponents suggested the bills went too far: Some districts that wanted to continue using seclusion wouldn’t have any rooms that complied with requirements in the bill. Additional training and reporting requirements meant more time and money, something educators generally can’t spare, opponents also argued.

Educators who testified during legislative debates underscored these points. Marvin Nordeen, a school psychologist in northern Michigan said he supported the package overall and trained others in behavioral techniques crafted to cut down on using seclusion and restraint.

But he argued lawmakers had to ensure educators could still legally restrain or seclude children.

“There are times when it becomes very dangerous, and we end up doing it whether we want to or not. It is the dirtiest part of my job,” Nordeen testified.

“When I leave at the end of the day, after having done that, I feel dirty. … Unfortunately it is a necessity at times, in some situations.”

While Calley, Liberati and others were successful in securing the measures’ passage, Calley wishes they could have done more.

Lt. Gov. Brian Calley in a meeting in January 2016 at Michigan State Office building in Flint. (Photo: Salwan Georges, Detroit Free Press) SALWAN GEORGES, DETROIT FREE PRESS

“I think it’s just human nature that people want to avoid accountability. In education, there are a lot of questions, a lot of scrutiny, a lot of reporting. Part of it, I think, is just fatigue (from) an industry that feels like they’re just under the microscope all the time, and this was just one more thing that they didn’t want to have to deal with,” Calley said.

The measures passed the Senate with almost unanimous support and the House with an overwhelmingly bipartisan majority vote. But the opposition of a few key lawmakers may have ramifications on any future legislative action.

∎ Lana Theis, then a Brighton Republican state representative, voted against the package. She’s currently the chairperson of the Senate Education and Career Readiness Committee, and is expected to win reelection this fall.

∎ Other current lawmakers who voted against the measure and are seeking reelection include Sens. Jon Bumstead, R-North Muskegon; Jim Runestad, R-White Lake, and Dan Lauwers, R-Brockway Township. All three voted against the package while serving in the House.

∎ State Sen. Tom Barrett, R-Charlotte, is running for Congress in mid-Michigan. He voted against the package while serving in the House.

∎ Former House speakers Tom Leonard, R-DeWitt, and Lee Chatfield, R-Levering, also opposed the package. During one committee hearing, Chatfield – a former private school teacher – said he has a child and sister with disabilities, and suggested the practices may be necessary in some circumstances.

Christine Greig was a House lawmaker at the time and sponsored bills in the package. The Northville Democrat, who went on to become the House Democratic leader in 2018 before leaving the Legislature in 2020, said she thought by the end of the legislative process that the legislative bill package was a success.

But after reviewing the Free Press investigation, she said it’s clear more needs to be done.

“To see now, after it’s been in place for several years, that we have some ISDs and some school districts that are going backward, is what it looks like, it’s just disheartening,” Greig said during a recent interview.

“Just looking at these numbers, we obviously didn’t go far enough with the accountability side of it, and the follow-up. To me, it just looks like a huge gap in the law right now.”

Greig stressed that she thought educators genuinely may need to use seclusion or restraint in rare circumstances, and if she were still in office she’d want to hold hearings about the tactics, the laws and what exact changes should be made.

But in theory, tying funding to reporting requirements may be a more effective way to ensure compliance with the law, she said.

“It’s tough to do to schools, but you can always use the power of the purse. If they’re not reporting things and complying, that there’s some kind of funding implications,” Greig said.

“You also want to look at, just, the public pressure you can put on a district through public transparency, too.”

‘He doesn’t need punishment. He needs help’

Cassie, Daniel and Kai Atallah hope revealing their struggles will help others.

Cassie had kicked around doing something for years, in part because Kai wanted to take action. She says he wrote and delivered a speech to the mayor of Holland about problems with seclusion and restraint.

There’s very little the mayor can do about statewide education policy, but Cassie said Kai felt the speech went very well.

“I told him, ‘Someday, I’m going to give you a voice. I’m going to give you a venue. We’re going to make change,’ ” she said.

For Cassie that started with a phone call to the Alliance Against Seclusion and Restraint, a national organization. After chatting with founder Guy Stephens, a Maryland native whose son was repeatedly secluded and restrained, Cassie connected with other Michigan parents of children with similar experiences. They’re organizing and preparing to take more concrete actions, such as speaking to the State Board of Education, to tell lawmakers about the problems they see.

Kai Atallah climbs trees on a recent day as he and his mom go on a field trip during the afternoon hours of his homeschooling in Holland. Kai had been homeschooled full-time for the past 2.5 years in response to the use of restraint and seclusion tactics by his previous school. Kai was diagnosed with autism during his kindergarten year and the use of seclusion negatively affected his experience in the classroom. CODY SCANLAN/HOLLAND SENTINEL

Cassie said they want lawmakers to evaluate whether both tactics are actually reserved for emergencies, potentially narrowing the legal definition. Lawmakers need to ensure educators have the training, time and resources necessary to respond to potentially problematic behavior in ways that do not lead to seclusion or restraint, she said.

“If seclusion is defined as something that’s legal here, that’s going to be in the back of their mind: If this doesn’t work, I can use that,” Cassie said.

After pulling Kai from school, Cassie said they spent the next six months “deschooling.” They traveled, saw family and visited national parks. Eventually they returned to a somewhat more structured day, but lesson plans are crafted to help Kai manage his emotions and designed to change if he’s particularly enjoying a subject.

He’s learning: Cassie said when Kai got really into the founding fathers, he memorized the entirety of the musical “Hamilton.” When they traveled to New York for a showing, he sat spellbound for the whole performance.

“He is just so far beyond where he was. He can handle so much more,” Cassie said, noting he’s also taking new medication that is helpful. “He doesn’t need punishment. He needs help.”

Kai said he loves his homeschool version of physical education class, but he noted he’s not learning only at home.

After considerable discussion, Cassie and Daniel decided to try public school again. They’re starting slowly; Kai is going to a special local public school program a few days a week.

Cassie and Daniel are happy, but cautious. They want to believe this can work, and that it is OK to trust another school system. After months of discussions, educators have agreed in writing not to seclude Kai.

“If you take away seclusion as an option, they have to rethink the whole process,” Cassie said.

But Daniel worries none of those agreements will matter in the heat of the moment should Kai struggle to regulate his emotions in the classroom.

He’s afraid educators – with no one to stop them – will ignore the agreement and put Kai back in the room they’ve worked so hard to flee.

UPDATE: After this story published, Shannon Brunink, head of school at Black River, wrote in an email response that the school's "practices are reflective of changes in the law in recent years and are consistent with MDE guidelines." He said the school intends to file data with the state to correctly reflect how many times students used its "time away room." He added that while at times a student is put in a conference room away from peers, a move that some would view as seclusion, the room's door is open and an adult works with the student.

This series was produced with assistance from the Center for Health Journalism at the University of Southern California as part of the 2022 National Fellowship at the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism.

Contact Dave Boucher: Dboucher@freepress.com and Lily Altavena: laltavena@freepress.com.