Family fled Michigan schools to get help for their son. They found it in Pennsylvania.

The story was originally published in Detroit Free Press with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism's 2022 National Fellowship.

Image from Detroit Free Press article

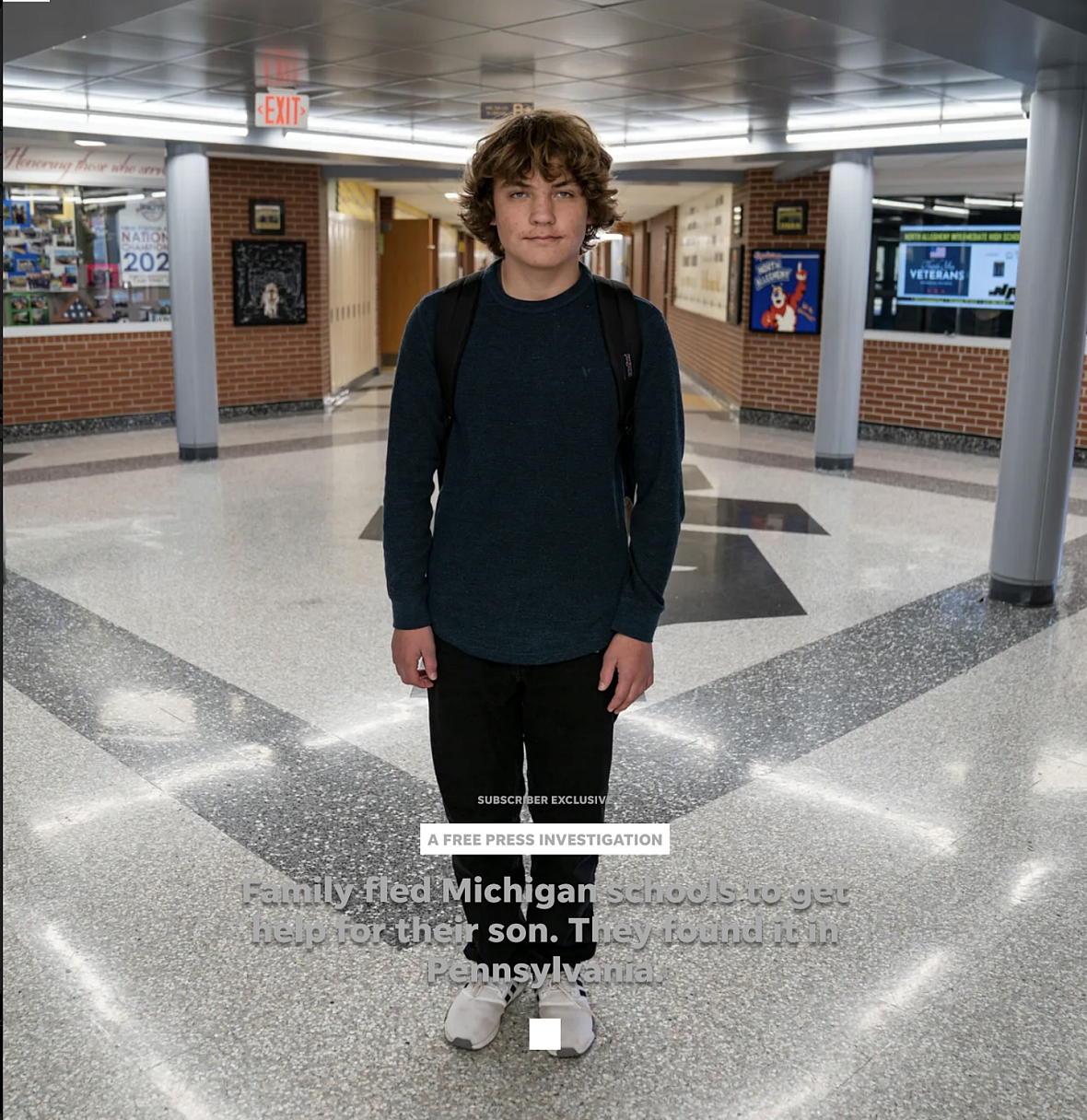

PITTSBURGH — In Pennsylvania, Bennett Solomond wants to go to school. School is where band class is. In the band, the high school sophomore plays the trumpet. Just before Halloween, he toured around his Pittsburgh neighborhood in a giraffe costume with members of the band, playing for homeowners.

In Michigan, where Bennett used to live, he did not want to go to school.

Sometimes, in Michigan, Bennett tried to run away from school. He got into arguments with his teachers at the Edison School in Hazel Park's school district. And if he wasn’t quiet or was rude to a teacher, Bennett would be escorted down his school’s hallway into the Center.

Inside the Center, a classroom-size room, a school staff member would usher Bennett into a cubicle-size space, his mother said, where he could sit on a cushion on the floor. There, he was surrounded by three bare walls that almost reached the ceiling — and one door, she said. Such isolation is called seclusion, a controversial tactic educators are allowed to use only in emergencies under Michigan law.

“It felt more like a prison cell than anything, because even if you tried to say, ‘I'm done now,’ they wouldn't let you out,” Bennett said.

Sometimes he’d spend just a few minutes inside the Center’s cube. Other times, documents show, he’d spend as long as 35 minutes in one of the cubicles. Sometimes he would go to the Center as many as five times in one day.

In Michigan, school was a constant source of frustration for Bennett. Fed up and cornered by a school system that seemed to constantly lead their son to a seclusion room, Bennett’s parents moved their family to Pennsylvania in 2019.

MANDI WRIGHT, DETROIT FREE PRESS

The disparities between Bennett’s time in public schools in both states illustrate how two different approaches to students with disabilities contributed to a boy’s success and failure. Bennett’s parents, Melissa Freel and Jay Solomond, contend that Michigan failed their son by secluding him often, leaving him scared of the educators around him.

But in his Pennsylvania school district, at first with the help of a Pittsburgh-area special education program, Bennett is thriving, they say, in part because the district does not use seclusion on Bennett.

The most recent federal data available from the 2017-18 school year indicates seclusion is used on far fewer public school students in Pennsylvania than in Michigan. In Pennsylvania, seclusion was used on six students per 100,000. In Michigan, seclusion was used on 114 students per 100,000, according to the data that includes grades pre-K to 12.

Educators at Bennett’s North Allegheny School District take regular crisis intervention training aimed at avoiding the use of seclusion. Unlike his schools in Michigan, Bennett’s school does not have a seclusion room.

For Bennett’s parents, the striking differences between their son’s treatment in Michigan schools and in Pennsylvania schools has led to a striking difference in their son’s behavior. By the time Bennett reached the Edison School in spring 2018, the kind, easygoing boy they knew as a toddler turned into a brooding, unhappy and traumatized preteen who hurled swear words at adults and threw school materials around the classroom.

In Pittsburgh, Freel and Solomond have seen Bennett make a transformation: happy and engaged with school, excited to show off his Lego collection to strangers and trick or treat.

“Our Bennett’s back,” Solomond said at his kitchen table in Pennsylvania, tears in his eyes.

Behavioral issues escalate

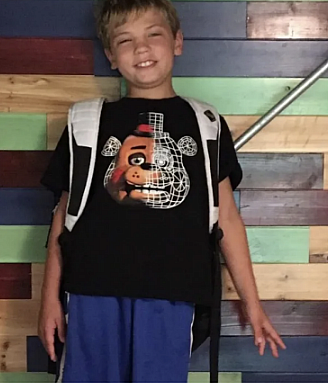

Bennett’s early years in the Troy School District were marked with problems in reading. In second grade, Bennett’s journey in special education programs began, starting with reading intervention.

By the spring of third grade and the beginning of fourth grade, Bennett’s behavior began to pose a challenge, as he started to refuse to go to school. Mornings before school turned into a battle. During recess one day in fourth grade, Bennett tried to walk home from school and was suspended, Freel said. School administrators continued to call the parents about Bennett’s behavior as it escalated.

During Bennett’s fourth grade year, Troy administrators moved him to Martell Elementary, where they told the family he would get more help from special education professionals, but Bennett’s behavior worsened.

In fifth grade, in the 2017-18 school year, educators used either seclusion or restraint — the act of forcibly restraining a child in crisis — 14 times on Bennett, according to Bennett’s education records, shared by his parents. Staff members cited physical aggression by Bennett.

But Bennett’s aggression, Freel said, was actually anxiety increasing because of frequent restraint and seclusion, which “looked like a kid literally fighting for his life when they (school staff members) put their hands on him. ... It looked like a kid pulling out every single swear word he thought he knew and then he learned some new ones.”

Troy spokeswoman Kerry Birmingham wrote in an email that she could not legally address a particular student's circumstances. But she wrote that, generally, Troy officials use seclusion only as a last resort, following state law. Behavioral staff members work closely with staff members to develop plans to support students, she wrote. specialized school for students with behavioral disabilities. The program, operated by Hazel Park public schools, takes children from across Oakland County and claims to offer an “educationally therapeutic setting.”

In the meeting with Bennett’s special education team in Troy, the parents said they were concerned that any use of restraint and seclusion could further traumatize Bennett.

Freel and Solomond said they were overruled by Troy educators in deciding to move their son to Edison.

Birmingham wrote that, in general, the decision to move a child outside of the district is "never taken lightly" and usually involves parents, Troy staff, behavioral health professionals and others.

MELISSA FREEL

“The highly structured, specialized and supportive program at Edison better meets Bennett’s needs at this time,” read notes from an Individualized Education Plan meeting in March 2018, explaining the decision to move Bennett.

Freel and Solomond had toured Edison before that meeting. The first place they were shown was the school’s seclusion room: the Center.

The Center

Edison operated on a points system. For every 10 minutes Bennett followed behavioral expectations in the classroom, he earned one point, according to Edison’s 2018-19 handbook. As students earned points consistently, they moved up to different levels. At the highest level, they could transition out of Edison and back to their district schools.

A daily points sheet would serve as a road map to Bennett’s behavior: whether he was “IMP” (impolite) or “NFD” (not following directions) or whether he was sent to “CTR” (the Center).

The Center, according to the handbook, is an area where students were expected to sit alone quietly, then take ownership for the behavior that led them to be dismissed from class in discussion with an adult.

To Bennett and his parents, the Center clearly represented seclusion, where he was left alone and adrift in a small room, in emotional crisis. Seclusion in Michigan, under state law, is supposed to be used in emergencies, only when a student could harm themselves or others. But the state does not monitor whether districts adhere to the law.

Day after day, educators sent Bennett to the Center, documents show. On one day’s point sheet, Bennett was sent to the Center after “talking back, giving staff a hard time.”

“It really broke me,” he said. “It made me think that like, this was all there was to life: People treating people with disabilities like they weren’t even humans.”

Bennett could hear his schoolmates in other cubes, he said. Some would be crying. Some would be swearing or yelling.

Amy Kruppe, superintendent of Hazel Park Schools, did not respond to reporter questions about whether the district considered the Center to be a form of seclusion. Kruppe, through district spokesperson Charles Pleiness, also did not answer questions about what the Center looks like. She wrote that the school only uses seclusion or restraint "as a matter of last resort" when there is a safety risk.

“Some students will have challenging moments in the learning process,” Kruppe wrote in a statement to the Free Press. “When that occurs, our team of staff utilizes a range of tools that allow students to de-escalate or engage in an appropriate fashion.”

Freel and Solomond held their breath and sent Bennett to therapy at first, hoping he’d move through Edison’s level system quickly and would go back to a general education program. But Bennett struggled and after the school abruptly changed his assigned teacher, he “fell apart,” Freel said.

One day in sixth grade, Bennett refused to go to the Center and started screaming, swearing, kicking desks and throwing shoes at his peers, according to records from Bennett’s time at Edison.

Maybe, she thought, she knew where that place could be.

“One evening I said, ‘I am taking this child to Pittsburgh,’ ” she said. “I said, ‘I'm going to go rent an apartment. I'm going to find a school. I'm going to find services there. And I'm going to get him the help that he needs.’ ”

Coping in Pittsburgh

During the summer break before his sixth grade year at Edison, Bennett had attended a therapeutic day camp called Quest Therapeutic Camps in Pittsburgh, a city where Freel had family. She drove Bennett to camp every day.

Bennett thrived.

April Artz, a licensed professional counselor who was director of the camp in Pittsburgh at the time, said she noticed Bennett would get wrapped up in a fight-or-flight mode in his head. Sometimes, he tried to run from camp or had an outburst.

Artz’s approach with children in emotional crises revolves around safety. If a child is in the midst of a dangerous outburst, she’ll direct everyone to clear the room and wait quietly as the outburst happens.

“We're going to have staff who know how to manage these things go in and most of the time not talk to this person because this person's already in a fight-or-flight state,” she said. “They wouldn't be picking up a chair if they weren't. We shut our mouths and we just wait until the person is able to be calm.”

Artz paid attention to what would trigger Bennett’s outbursts at camp, saying competitive games were often an impetus.

As Bennett prepared for another school year, Freel said Artz told her she believed Bennett was autistic. Though Bennett had been surrounded by special education professionals in Michigan, no one raised autism as a possible diagnosis, Freel said.

Back in Michigan, Freel sought a diagnosis, but she said a psychologist told her it wasn’t worth the effort, and that it wouldn’t help the family receive services in and out of school.

Bennett returned from Pittsburgh’s Quest to Edison in Michigan and struggled.

Freel kept thinking about Pittsburgh.

By June 2019, the family was ready to move, even though it meant upending their lives in Michigan, where they had lived and worked for decades.

Once they were there, Artz helped confirm Bennett’s diagnosis. Bennett started at the Watson Institute, a special education school in the Pittsburgh area. In therapy, Artz has helped Bennett learn to identify his emotions and express them before he gets too overwhelmed, in an effort to help regulate those emotions before an outburst.

During his first few weeks at Watson, Bennett had an outburst, Freel said. And staff responded to the behavior in a completely different way than educators did in Michigan.

“They had me come to school and get him,” she said. “They put a social worker in the car with me and we drove to this pediatric program. We had him assessed right then and there, and we had new medications for him. We had a meeting within a week, and the whole plan was changed to support him differently.”

Freel saw educators respond to Bennett with kindness, and Bennett responded.

By fall 2021, Bennett started transitioning from attending Watson full time to attending his area public school a few days a week. A sprawling high school with more than 1,000 ninth and 10th graders, North Allegheny Intermediate High School can sometimes be overwhelming, but Bennett has a place to excuse himself if the environment becomes too much for him.

But it is just a regular classroom, which is open all day and where a teacher assigned to emotionally support Bennett is stationed, Assistant Principal Jenna Fraser said.

‘Typical kid stuff’

Bennett blows a low note into his trumpet as his symphonic band class warms up.

The band played during football games all throughout the fall. Football is a big deal in western Pennsylvania.

In class on a Wednesday in November, Bennett seamlessly blends in with his classmates. They whisper to one another. Then they roll into their rendition of “Under the Cherry Blossoms,” a sweeping orchestral number. Bennett taps his foot to stay with the song as cymbals clap near him.

He finally feels like he is in a safe place.

“I feel like I’m in a learning environment and I don’t have to worry about it,” he said.

Bennett now attends North Allegheny Intermediate every day of the week. After school, he comes home to his Lego collection and his dog, Bear. Bennett loves his Disney-themed Legos, all intricate and immaculately constructed in a corner of the living room.

The last two years, to Freel and Solomond’s overwhelming relief, have “been all about typical kid stuff,” she said.

Bennett’s remarkable progress comes with an asterisk: Freel and Solomond said they had to move out of state to achieve it, a feat they acknowledge takes privilege and time many Michigan parents and guardians of students with disabilities do not have.

“There are kids that this isn't even a reality, this isn't even a dream,” Freel said. “This isn't even a wish to be able to have their parents literally pick up and move and get their kid out of a difficult situation.”

Did you like this story? Your support means a lot! Your tax-deductible donation will advance our mission of supporting journalism as a catalyst for change.