26 Michigan school districts want to charge Free Press $85,000 for public records

The story was originally published in Detroit Free Press with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism's 2022 National Fellowship.

Detroit Free Press

Alone in a school social worker’s office, forced to remain inside but wailing to leave, Amanda’s 7-year-old son grabbed up a butter knife and picked at the room’s door handle.

That day in 2017 was a turning point for Amanda, marking the moment that seclusion — the act of isolating a child in crisis alone in a room — transformed and traumatized her son. The Free Press is only using Amanda’s first name, to protect the privacy of her son.

As years passed, Amanda became angry.

And curious.

Curious about how often Farmington Schools, the district he attended, used seclusion and restraint on all of its students with disabilities — students like her son, who has autism.

Michigan educators have secluded and restrained students nearly 94,000 times over the past five school years, a Free Press investigation found. Among the students who are subjected to those tactics, 4 out of 5 have a disability. Under state law, these tactics are supposed to be used only as a last resort in emergencies, though some records indicate that educators are turning to these tactics in nonemergency situations.

Amanda, aware that taxpayer-funded organizations such as school districts must follow public records laws, requested documents that would include the details of every instance of seclusion and restraint in the district from 2017 to 2021. Farmington administrators responded with an invoice for $3,362, claiming it would take 88.75 hours to find the records and then black out students’ names and other sensitive information.

“That's really concerning, because the law states this data has to be closely monitored,” Amanda said.

We requested documents, too — From Farmington and 46 other districts around Michigan.

Twelve districts responded with records. Six districts — Montcalm Area ISD, Kentwood Public Schools, Bay City Public Schools, Allegan Area Educational Service Agency, Berrien RESA and Kalamazoo RESA – denied our request. Kentwood Public Schools, a very large west Michigan district, said the records did not exist, despite telling the state educators secluded and restrained kids more than 1,300 times during the years requested by the Free Press.

A smaller district also blamed “a coding error” by a new principal and “a lack of oversight by a new superintendent” for reporting to the state more than 100 instances of seclusion or restraint the district now says never happened. .

Two never responded.

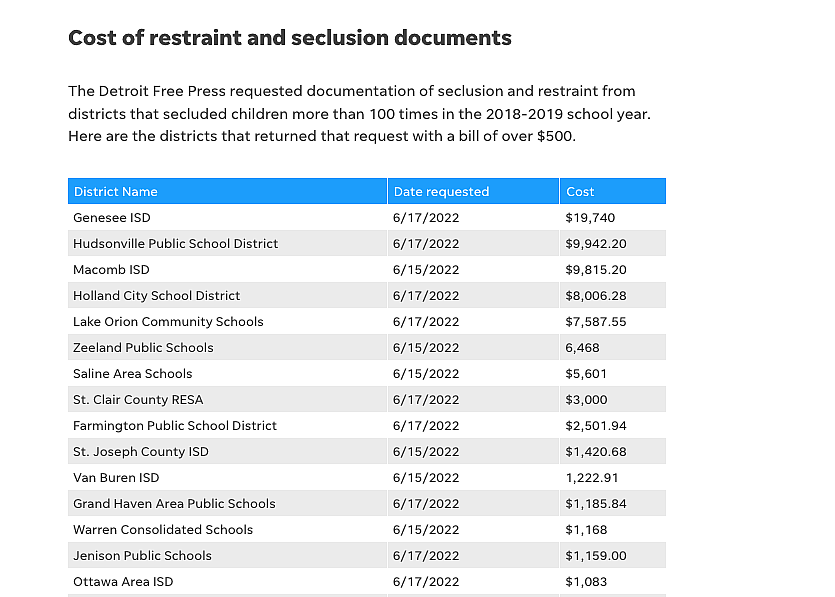

Twenty-six responded to our requests with invoices, asking the newspaper to pay a wide range of fees for the documents, from $167 to $19,740, for a total of nearly $85,000.

Our request was similar to Amanda’s: We asked for documentation of every incident of seclusion and restraint for two school years, documents schools are required by state law to complete every time a student is restrained or secluded.

The Free Press has declined to pay fees in the thousands of dollars, arguing these records are public and should be released for free or nominal costs.

Most of the school districts we requested records from used seclusion more than 100 times in the 2018-19 school year, the starting point of our yearlong-plus investigation into seclusion and restraint practices in Michigan schools.

Below is a list of the districts asking for $500 or more in fees. This list will be periodically updated as districts respond and reporters continue to try to negotiate for lower fees.

Can public schools charge records fees?

Yes, public school districts and other public agencies in Michigan can charge fees for public records under state law. Government bodies are allowed to charge fees for copying records and other labor associated with fulfilling the request.

But some fees imposed by public agencies have become exorbitant.

The law specifies that if an agency charges an hourly rate for locating and examining the records, they must not charge more than the hourly wage of its lowest-paid employee capable of doing the work.

Some districts charged hourly rates as high as $81 an hour, as was the case with Holland Public Schools.

St. Clair County Regional Educational Service Agency, another district that uses seclusion and restraint, said it would cost $70.50 an hour for someone to review and redact the documents, equivalent to an annual salary of $146,640.

Jean Sturtridge, director of legal services with St. Clair, wrote in an email that the hourly figure represents the wage of someone who could ensure “legal compliance.”

“I took the rate of pay of the least paid individual with the knowledge and training to ensure legal compliance and determined her hourly rate,” she wrote.

Genesee Intermediate School District charged the most for records, at $19,740. It estimated needing more than 123 hours to review and black out sensitive information from approximately 1,974 records – that’s $10 per record.

Lake Orion Community Schools’ officials said it would take 141 hours to even locate and retrieve the records – more than three business weeks of non-stop work to find documents that are supposed to be maintained and analyzed annually in order to reduce seclusion and restraint districtwide.

But it did determine someone making $14.33 an hour could review the documents for sensitive information.

Legislature routinely rebuffs reform

State lawmakers have argued that high records fees stand as barriers between the public and the government.

State Rep. LaTanya Garrett, D-Detroit, in 2019 proposed making public records free.

"I feel like it should be free. The public feels like it should be free," Garrett said in an interview at the time. "You're not open if you want to charge someone $1,200 for public records.”

Garrett’s bill did not advance in the Legislature.

Independent evaluators frequently rank Michigan as one of the least transparent states. Although Republican and Democratic elected officials have repeatedly vowed to increases access to public records, legislative efforts continue to fail.

This series was produced with assistance from the Center for Health Journalism at the University of Southern California as part of the 2022 National Fellowship at the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism.

Contact the reporters: Laltavena@freepress.com and dboucher@freepress.com.

Did you like this story? Your support means a lot! Your tax-deductible donation will advance our mission of supporting journalism as a catalyst for change.