Life and Death: When Police Criminalize Young Black Men

This story was originally published in Word in Black as a project for the 2022 Data Fellowship, a program of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism.

Abraham Jarvis, 18, poses for a photo at John F. Kennedy Park in San Diego on Feb. 10, 2023. Last year when Jarvis was 17, he was ticketed and briefly detained in the back of a police car for “switching lanes,” one example he says of him experiencing racial profiling. While being photographed, two police cars were parked in the distance.

(Anissa Durham/Word In Black)

When Abraham Jarvis gets pulled over by police, he has a rule with his parents: they FaceTime.

He started driving at 15. Born and raised in San Diego, getting pulled over by the police started as soon as he was behind the wheel. Jarvis, now 18, met me in February at a park near Lincoln High School.

As Jarvis and I sat on a picnic bench, the sun was bright and shining on his face. I watched him surveil the area, and it quickly became apparent he was scanning for the police. Shortly after sitting down, a police car pulled up.

20 minutes later, a second police car arrived.

With his back turned toward the police cars, he periodically checked to see where the police cars were parked. As I snapped photos of him for this story, he looked back to check if the police cars got any closer. They did.

Jarvis is a smart teen; he’s been an Aaron Price fellow — a prestigious service opportunity for San Diego youth — since his freshman year in high school. Due to several encounters with the police, his mom pushed him to finish school a semester early. Now awaiting his June high school graduation ceremony, Jarvis plans to join the Army this summer.

But, the last couple of interactions he’s had with San Diego police has left him shaken and uncertain.

They grabbed me and put me in handcuffs. And they put me in the back of a cop car.

In July 2022, Jarvis was making a quick run to a store that’s no more than five minutes away from where he lives. On his way home, he switched lanes. Then cops pulled him over. Already on FaceTime with his parents, the officer asked him why he was nervous.

What followed was a series of questions: police asked if there are drugs or guns in the car, if he’s committed a crime recently, and why his heart was beating out of his chest. Then cops said to get out of the car, or they would pull him out themselves.

Without permission to search the car, Jarvis complied out of fear for his life.

Abraham Jarvis, 18, poses for a photo at John F. Kennedy Park in San Diego on Feb. 10, 2023.

(Anissa Durham/Word In Black)

“Then they grabbed me and put me in handcuffs. And they put me in the back of a cop car,” he says. “All that for a simple supposed traffic violation.”

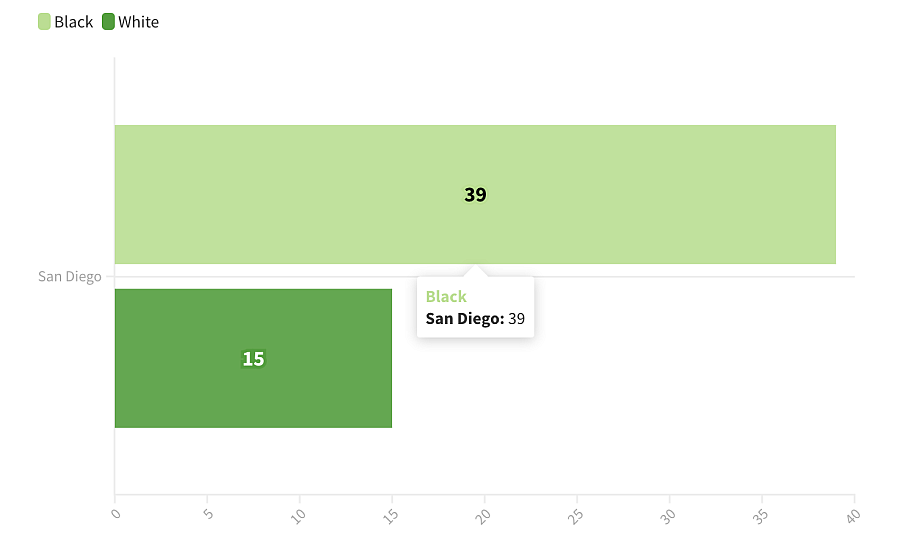

Black people only make up 6% of the population in the city of San Diego, but a quarter of all use of force incidents was against them. According to the Center for Policing Equity, National Justice Database, Black people were subjected to force by San Diego police officers nearly five times as often as white people. And between 2016-2020, Black people were searched more than two times as often as white people during a traffic stop.

Source: Justice Navigator •

Graphic by Anissa Durham

“That experience was frustrating, to say the least. Because I’ve never experienced something like that where I felt so powerless,” Jarvis says. “Because it’s like you’re stripping away my freedom.”

Always a Reason to Search Black Youth

Laila Aziz is the director of Pillars of the Community, a faith-based organization focused on helping people impacted by the criminal justice system in San Diego. She was brought into her work as a means of survival. After watching loved ones be affected by the disparities in policing and the criminal justice system, she decided to take action.

There are “disparities in how we’re looked at in the system — there’s always a reason to try to search a young Black person, a teen, and also a Black woman,” Aziz says.

“To the people that are not from our community, or don’t know our community, our young people are looked at as older than they are in those same situations. We have a stacking of different biases that work together to create a discriminatory practice itself.”

San Diego has a problem with illegal search and seizures, she says. Advocates like Aziz continue to call out the racial profiling tactics within the San Diego Police Department. Despite SDPD making efforts since 2020 to diversify the police force, discriminatory practices continue to ensue.

We want to reimagine public safety, and we want to do that in hand with our community.

Footage was recently released of a 2020 incident with a drunk now-former San Diego police officer. The man is on film saying, “I kill [Black people] for a living. I am a cop.” 29 days prior to the arrest of the inebriated officer, he killed a 31-year-old Black man who, according to reports, resisted arrest.

But in another incident in 2021, sergeant Brandon Woodland was caught on an officer-worn body camera stating his K-9 dog only likes to bite “dark meat.” Woodland continues to serve on the police force.

Laila Aziz poses for a photo inside Pillars of the Community in Southeastern San Diego on Feb. 14, 2023. Aziz filed a complaint on behalf of Abraham Jarvis who says he has been racially profiled by San Diego police officers.

(Anissa Durham/Word In Black)

The history of policing dates to the 1700s. The “Slave Patrol” was created to control and deny access to equal rights to freed Black slaves. In the 1900s, local municipalities started to establish police departments — with the purpose of enforcing Jim Crow laws.

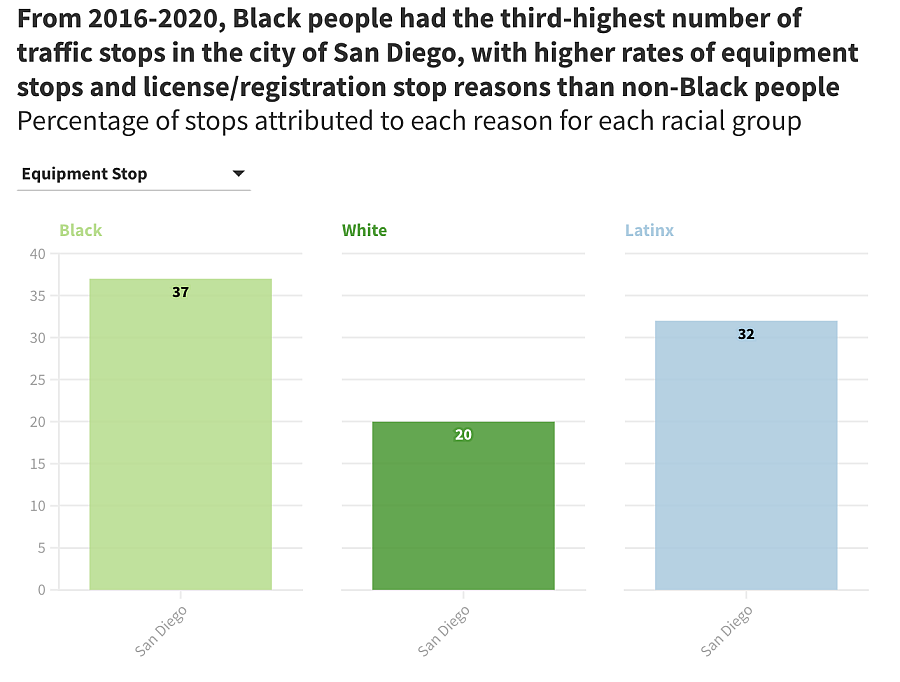

More recently, from 2016-2020, Black people had the third-highest number of traffic stops in the city of San Diego, with higher rates of equipment stops and license and registration stops than non-Black people. Equipment stops include unlawful vehicle modifications: window tinting, removal of mufflers, and lowering or raising of a vehicle.

Source: Justice Navigator •

Graphic by Anissa Durham

“We want to reimagine policing,” Aziz says. “We want to reimagine public safety, and we want to do that in hand with our community.”

This reimagination involves a few things. Pillars of the Community works within the community to eliminate systems that are oppressing Black folks by holding police accountable and amplifying and uplifting the stories of those who are oppressed.

This is exactly why Aziz’s organization is working with Jarvis. After numerous stops by police, nothing has ever been found in his car. Because of this, Aziz has filed a complaint against the police department.

“He’s an Aaron Price fellow. He’s a straight-A student. He’s one of the cream of the crop in our community,” she says about Jarvis. “But to the police, he is a young Black male.”

“These Dudes Can Take My Life”

Jarvis has two younger brothers who are 9 and 13-years-old. He worries for their safety as they get older and start to drive. He talks to his brothers regularly about what it means to be a young Black man in this country. He’s preparing them for potential future interactions with police — repeating the conversations that started with his parents.

He says the fear he has of being racially profiled and stopped by police is something he doesn’t wish on anybody.

“When those events happen in my life, it does kind of mess you up because you feel powerless,” Jarvis says. “These dudes can take my life. And it’s out of my control.”

Abraham Jarvis, 18, poses for a photo at John F. Kennedy Park in San Diego on Feb. 10, 2023.

(Anissa Durham/Word In Black)

When asked what his parents say about his traffic stops, Jarvis says his mom is even more scared than he is. The last thing he wants to see is his mom stressed about him driving. But since Jarvis helps with the school pick-up of his brothers, their family has no choice but to live on edge.

Trying his best to keep a positive attitude, Jarvis says he started going to therapy. This gives him the space to express himself and process the scary, draining emotions attached to being stopped by the police. Now, he considers himself to be mentally strong — mostly out of necessity.

“I carry myself every day with positivity,” he says. “Even if they stop me, at least I’m still here. I get to drive back to my family.”

The Pipeline to Prison Isn’t Just in California

Kahlib Barton, 32, is the co-director of technical assistance at True Colors United, an organization focusing on the experiences of LGBTQ youth. As a non-binary person, Barton uses he/they pronouns. Growing up in the small town of Marshall, Texas, they said it wasn’t easy.

During their teen years, Barton was caught with marijuana multiple times by police. At age 15, they were arrested for possession.

Kahlib Barton, 32, poses for a photo at Hermann Park in Houston on Feb. 25, 2023. During high school, Barton says they were criminalized and adultified as a Black teenager.

(Aswad Walker/Word In Black)

During that time, Barton’s mom wanted them to go to outpatient rehab, out of fear they would eventually end up in prison for marijuana. After spending a few days in jail, Barton received rehabilitation support to help them stop smoking weed and went to Narcotics Anonymous meetings.

“For a very long time, I blamed myself, and I think I still kind of struggle with that,” they say. “I still take a lot of responsibility for all of that.”

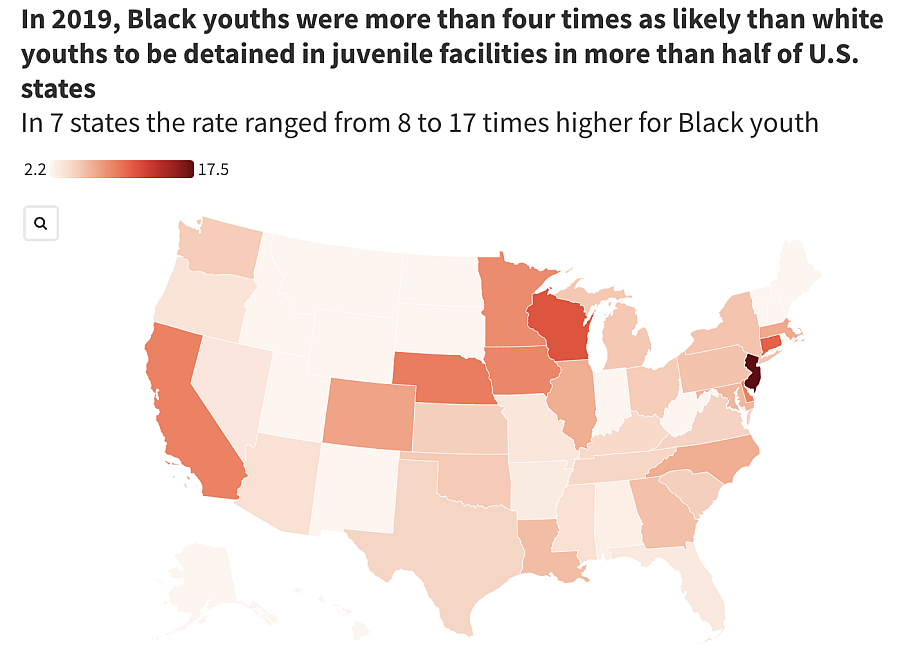

Black youth are more than four times as likely to be detained or committed to juvenile facilities as their white peers, according to data collected by the Sentencing Project in 2019. In Texas, Black youth are nearly five times more likely to be incarcerated.

Source: Sentencing Project

For states that did not have available data, the rate was set to zero.

Graphic by Anissa Durham

For a few years, during Black History Month, Barton’s high school partnered with a local college in the city to do a step show. Later, Black students wanted to create their own fraternity or brotherhood for the school.

Students submitted a handbook to school administrators, detailing the grade and conduct requirements to participate. But Barton says the white principal saw the students wearing logos for their club and doing dances — and viewed them as a gang.

“We almost got expelled from school because of it,” they say. “At the time, we didn’t think of it as adultification, we just saw it as racist. But, in hindsight, they were viewing us not only as Black but as much older than we were. And assuming that we had some type of gang influence.”

Kahlib Barton, 32, poses for a photo at Hermann Park in Houston on Feb. 25, 2023.

(Aswad Walker/Word In Black)

“I just felt like I was constantly being targeted based on my identity,” they say. “This specific instance, it was like my blackness was on trial, and then later on, it was my queerness.”

The school-to-prison pipeline is a national trend where youth are funneled from public schools into juvenile detention and criminal legal systems. Black and Brown youth are most affected by this pipeline.

I don’t trust no damn police.

Contributing to this issue are current zero-tolerance policies enforced in schools that criminalize minor infractions of school rules, by suspending or expelling students.

Research shows schools with a police presence lead to an increase in Black students being arrested for minor infractions and harsher punishments. Black students with a disability are also more likely to be fed into the carceral system.

“I don’t trust no damn police,” Barton says. “I have a very healthy skepticism of school systems, specifically, and their connections to prisons and other institutions that are racist.”

This story is part of the Lost Innocence: The Adultification of Black Children series, and was produced in collaboration with the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism.

Did you like this story? Your support means a lot! Your tax-deductible donation will advance our mission of supporting journalism as a catalyst for change.