If Parents Don’t Protect Their Kids From Abuse, Who Will?

The story was originally published in Word in Black with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 Data Fellowship.

Cherry DeJesus looks at a photo of herself as a 4-year-old girl in her New Jersey home on Feb. 26, 2023. She’s a survivor of child sexual abuse and experienced hypersexualization as a child.

(Chantel Philip/Word In Black)

Cherry DeJesus was a young Black girl growing up in Paterson, New Jersey, in the 1970s. She knew earlier than most: no one was going to protect her — not even her own mother.

DeJesus says she was molested by several family members and neighbors. Her earliest memory of sexual abuse was at age 5.

“I don’t know about protection,” she says.

DeJesus’ aunt was her babysitter growing up. Her aunt’s husband would abuse her while her aunt was asleep after working the night shift.

“I don’t think my mom thought my uncle would touch me, too,” DeJesus says.

A parent, an adult, or a loved one can protect a child from abuse. But what happens when they don’t? When a child is expected to speak up or to just take the abuse, what does that say about how we view children — especially Black children?

The abuse continued for eight years until she was 13. DeJesus says between the ages of 7 and 8, older men would call her house looking for her father — and they’d ask sexual questions about her.

While in elementary school, young boys would make sexual jokes about her body. Teachers told her to “suck it up” and labeled her a “crybaby” when she felt uncomfortable by those comments.

“I think it made me not be able to speak up,” she says about the adults who forced her into silence.

At 10, her body started to develop earlier than other students. This intensified the sexual comments and “jokes” about her body, both from peers and teachers. But neighbors and adults outside of school treated and expected DeJesus to act like a woman. Despite being in the fourth grade.

Cherry DeJesus holds a framed photo of herself as a little girl in her New Jersey home on Feb. 26, 2023.

(Chantel Philip/Word In Black)

For many Black girls, DeJesus’ experience is not uncommon. The 2017 Georgetown Law study, Girl Interrupted: The Erasure of Black Girls’ Childhood, details the intersection of adultification bias and its roots in sexualizing Black girls. A common stereotype knowingly and unknowingly placed on Black girls is society’s expectation that sex is part of their natural role.

As a result, the study shows Black girls are viewed as more adult-like than white girls. Black girls are perceived to know more about adult topics and sex than white girls. And Black girls as young as 5 were more likely to be viewed as behaving or seeming older than their age.

The perceptions of Black girls often come from within the household. Word In Black circulated a survey, “Are Young Black Bodies Treated, Viewed, or Seen Differently Than Others?” for two months. Of the dozens of respondents, those interviewed often said comments about their bodies usually came from their family members.

I think it made me not be able to speak up.

This perception that Black children are sexual beings directly impacts the health and well-being of the adults produced from that stereotype. Word In Black spent months reporting on the correlation between the adultification bias and hypersexualization of Black children. One thing is clear: most Black people have experienced this bias as a child.

But no one person or adult is to blame for this experience. Adultification bias is rooted in anti-Blackness and dates back to slavery. Each experience is different, but the thread remains the same: Black children are treated like they are undeserving of childhood.

It’s become so common to label Black girls as “fast,” “curvy,” “promiscuous,” or “grown,” that for some parents and adults around Black children, it’s sometimes seen as protection. Some Black parents label their children with these names as a tactic to ‘prepare’ them for the anti-Black society around them.

But it usually has the opposite effect.

Georgetown’s researchers also found Black girls are also perceived as needing less protection and nurturing than white girls. DeJesus, now 55, knows what that’s like. When she was 10, she told her mother relatives were sexually abusing her.

“When I told her that part, she believed me,” she says. “That particular person that was touching me had done the same thing to her. And that was a big shock.”

Cherry DeJesus poses for portrait photos in her New Jersey home on Feb. 26, 2023.

(Chantel Philip/Word In Black)

After telling her mother, she was separated from the relatives who were sexually abusing her. She later became a latchkey kid and was more isolated. But for DeJesus, the abuse continued for two more years — until she was forced to protect herself.

“I started dating — like I had a boyfriend for protection,” she says. “It seems like I always picked the bad boys, so nobody would bother me after that because they were scared of the boyfriend that I had at the time. I think that’s kind of where it stopped.”

And that’s when the comments from teachers and other adults came in. They labeled her as fast, promiscuous, and grown for having a boyfriend at 13.

“It makes me feel sad,” DeJesus says. “It wasn’t so much that I was being fast, I was doing it for my protection. They saw it one way, but it was how I was protecting myself.”

Experiencing child sexual abuse took its toll. In her teen years, she became more isolated, quiet, and reserved. From her teens to mid-20s, she considered harming herself and had suicidal thoughts.

Raising her own children, DeJesus says she was very protective of her daughter while she was growing up. And she continues to be hypervigilant of other young children — in hopes of protecting them, too.

When We Harm Black Girls, We Harm Ourselves

Terri Watson, an associate professor of educational leadership at the City College of New York, has done extensive research on Black feminist theory and motherwork. She says Black girls are often not given the space to define themselves and figure out who they are.

“I think Black girls are taught to be women, meaning they’re adultified and given these burdens and asked to play mammy,” she says.

For many Black children, continuing this trope into adulthood is common. Black girls who were expected to mother as a child oftentimes continue to mother others as an adult. Watson says this shouldn’t be a role expected of Black girls.

Terri Watson, associate professor of educational leadership at the City College of New York

“As a Black woman, as a former Black girl, and as a mother of a Black girl — I think we need to … allow Black girls to be just that, Black girls and experience the full range of emotions as everyone else does,” she says.

Historically, caricatures of Black girls and their bodies depicted them as hypersexual and glorifying sex — like the Jezebel stereotype. This stereotype predates the slavery era when European travelers to Africa found scantily clad natives, and this partial nudity was misinterpreted as lewdness, according to Ferris State University. During slavery, white men raped enslaved African girls and women — this stereotype of Black girls being sexually aggressive provided rationale for the sexual assaults.

More recently, the National Center on Violence Against Women in the Black Community reports that one in four Black girls will be sexually abused before the age of 18. And one in five Black women are survivors of rape.

“I think when we harm Black girls, we harm ourselves,” Watson says.

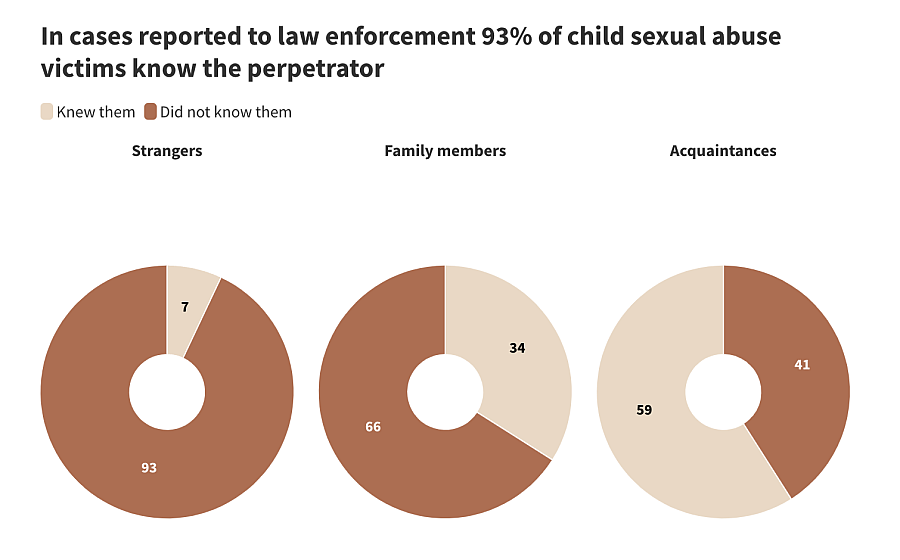

In cases reported to law enforcement, most child sexual abuse victims know the perpetrator, with 59% being acquaintances, like family friends, and 34% being family members, according to 2016 data from RAINN.

Source: RAINN

Graphic by Anissa Durham

“We have to talk about how we perceive Black girls,” Watson says. “How we don’t celebrate them, don’t uplift them, don’t recognize their creativity and ingenuity.”

When Your Parent Doesn’t Protect You

Cynthia Guest, 56, lives in South Bend, Indiana. She knows all too well what it’s like to not be afforded a childhood. One of the first experiences that stripped away her childhood started at age 4 — when she was molested by a male babysitter.

“My mother … said that it was my fault, so they kept using them as a babysitter,” she says.

The abuse continued for two years, even after pleading to get a different sitter. Guest can’t remember why it stopped. But she thinks it was because her family moved, or the sitter graduated from college.

“It was very painful to finally get up the courage and say this happened to me, and then be told, ‘that’s your fault,’” she says.

Growing up in her household, Guest says her mother accused her when she was a little girl of trying to be fast, hot, or a whore.

I think that you always feel that that’s how people look at you, just for sex.

At 6, she wanted to be a ballerina. While taking ballet classes, her mom said her “butt looked like a loaf of bread.”

As a child, she was also not allowed to make mistakes because she would be called “stupid or dumb.” Guest is the oldest girl of her siblings. She would make breakfast, iron clothes, and make sure her brother and sister were ready for school — at age 9.

At 12, she lived in a foster care home. At night, the foster dad would get drunk and come into the room where Guest and the other girls slept.

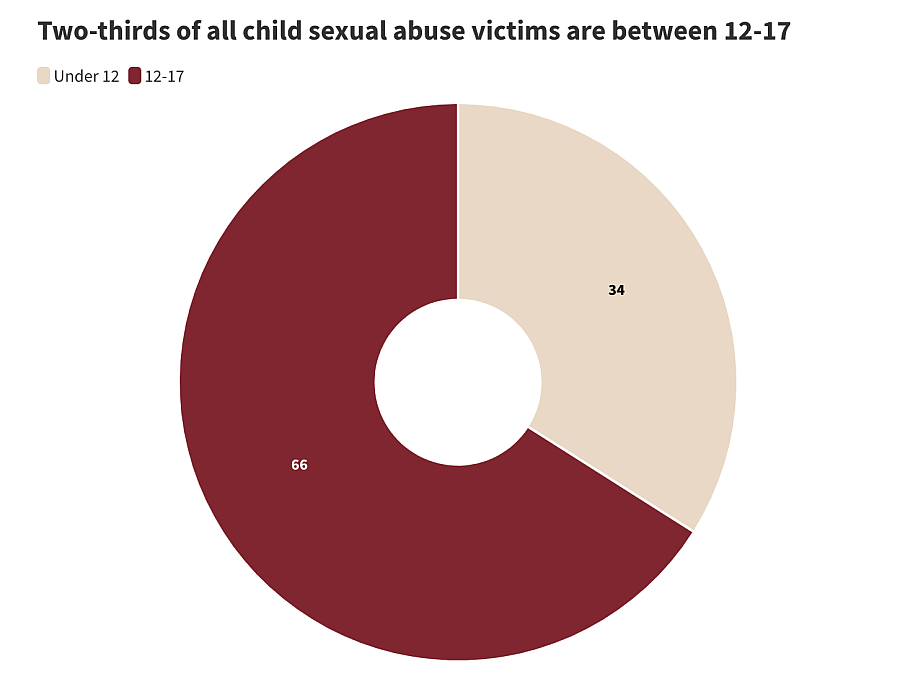

According to 2016 data from RAINN, more than 80% of child sexual abuse victims are girls, and two-thirds of all child sexual abuse victims are between 12-17.

Source: RAINN

Graphic by Anissa Durham

Like most survivors of childhood sexual abuse, Guest says she became very defensive and never trusted anybody. She joined the Army at 18. Now, as a police officer, she often works in elementary schools to teach a drug awareness program.

“It’s one of the reasons that I do this: I can tell little girls who have that same anger and I know that something’s happened,” she says. “I can see that hurt. I can see that pain.”

Working in the schools allows her to connect with other Black children who are experiencing sexual abuse. Guest says non-Black teachers need to do a better job of not mistaking a Black child’s “toughness” as a ploy to over-discipline. She knows from her own experience, for some of these children, being tough is really a barrier they put up to protect themselves from getting hurt.

“I don’t think it’s something you ever get over,” Guest says. “And I think that you always feel that that’s how people look at you, just for sex.”

Did you like this story? Your support means a lot! Your tax-deductible donation will advance our mission of supporting journalism as a catalyst for change.