Shadow Pandemic: What can be learned from the pandemic’s domestic violence rates

This article was produced as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 California Fellowship.

Other articles include:

The Perfect Storm: How domestic violence escalated during COVID-19

The Signal

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated already-dangerous dynamics for victims who were trapped at home with their abusers. Advocates say it was difficult to get help due to backlogs at shelters and in the criminal justice system, leaving many to ask: “Where do we go from here?”

According to a number of local experts and law enforcement officials, there are two key components to the domestic violence system that require additional support or insight in order to cure the ills that were largely exposed during the COVID-19 pandemic: funding and a lack of education.

Follow the money

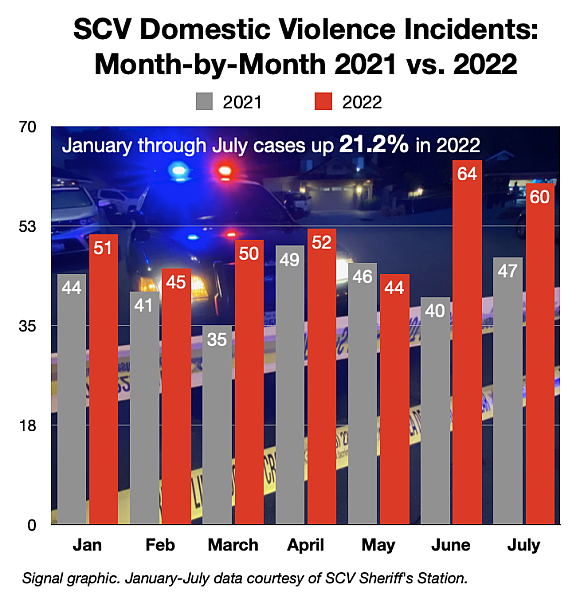

Domestic violence incidents in the U.S. increased by 8.1% following the imposition of lockdown orders during the 2020 pandemic, according to a study published by the National Commission on COVID-19 and Criminal Justice.

The Santa Clarita Valley and Los Angeles County were no exception to the trend, but local domestic violence officials say funding mechanisms during the pandemic failed to keep up with the rise.

With little money to go around, and fundraising events not being available, charities, including those in the domestic violence space, saw donations drop off.

“If we didn’t fundraise, we couldn’t do what we do,” said Marc Winger, president of the SCV Child and Family Center’s board of directors. “So, it’s a constant in these kinds of programs that there’s never enough state and federal funding, and they’re very rigid.”

According to Joan Aschoff, president and CEO of the Child & Family Center, the problem results in the center being unable to fund even the basic necessities for its programs.

“Once [survivors] get into our emergency shelter, it is so difficult,” Aschoff said. “Emergency shelters are funded for 30 days — that’s it. For people who have resources, that’s OK, that gives them enough time to get some resources and support and then they can make arrangements and they go on and hopefully don’t return to the batterer. But for those that don’t have resources, housing is such an issue.”

Rebuilding someone’s life takes more than 30 days, especially when doing so from scratch and often without a support system, Aschoff said.

In addition to the underlying trauma of surviving a long-term domestic violence situation, survivors often need to receive job training, mental health treatment and assistance with the children who accompanied them.

And outside of the lack of funding for resources that directly benefit survivors, another issue facing these organizations is the staff shortages, also known as the “vacancy factor.”

A vacancy factor, according to Aschoff, involves a business or organization not running at a fully staffed capacity. And while this was true for most businesses, the pandemic especially hit local domestic violence programs.

“We would normally run a vacancy of, say, 8%, but (during the pandemic) we went all the way up to 20% vacancy for a bit,” said Aschoff. “The last time I looked, I think we were around 15 or 14%, which is a great improvement, but there were months where we were at 20%, and it’s taking a lot longer to fill positions.”

According to Winger and Aschoff, the vacancy rates were created and continue to still be an issue due to budget constraints, employees wanting to change their working styles — wanting to work from home — among a number of expectations that arose during and after the pandemic.

Although the shortage hasn’t necessarily resulted in the cutting of programs, it does mean that there are fewer people to provide the services, meaning mental health or substance abuse services, for example, have become thinner and thinner.

Moreover, the pandemic has resulted in many — including some of those who’ve gone through extensive training and sensitivity courses to become fit to be domestic violence advocates — going into other fields due to the lack of pay, both Winger and Aschoff agreed.

“A domestic violence advocate makes about $16 an hour,” said Krysta Warfield, who now works at Haven Hills in Canoga Park. “You’ll find people making more working at McDonald’s.”

When asked why the funding gap continues for domestic violence services in L.A. County, all three advocates — now working in Santa Clarita and Canoga Park — said that the issues range from the bureaucratic red tape, to unrestricted-versus-restricted funding, to having the time to hire enough full-time grant writers.

And although the legal system and various courts around L.A. County have returned to business as usual as the pandemic continues to wane, an issue continues to persist for victims that became apparent during COVID-19: the cost of legal counseling.

According to Warfield, the fees begin to add up, especially if there are other legal matters to be settled — such as an eviction — which ultimately results in many survivors left on their own before the judge to plead their case.

“It has always been very underfunded, especially the legal aspects are very minimally funded,” she said. “So, even whenever we collaborate with the attorney, family law cases can turn from $5,000 to $50,000 to $100,000 very quickly.”

Righting the wrongs through education

According to a number of advocates, the de-stigmatization surrounding domestic violence is paramount in not only helping them to attain more funding, but also ensuring that more survivors come forward to report incidents.

“People still think it’s a choice,” said Warfield, referring to domestic violence. “It’s a very common misconception when people don’t understand all of the dynamics that go into DV and trauma and all of these things … they say, ‘Well, they can just leave.’”

Capt. Justin Diez of the Santa Clarita Valley Sheriff’s Station said that when his detectives conduct followup investigations to get a victim’s statement, the victims often refuse to cooperate out of fear of retaliation from their abuser or uncertainty of what their life will look like following the incident.

“Oftentimes, the man is the breadwinner, right?” Diez said. “Maybe the woman stays home with the kids or she hasn’t worked in many years because she had kids. They go testify against him and he’s in trouble or he goes to jail and then they don’t have anywhere to go live or they’re not going to have any money. And it becomes an ongoing cycle.”

According to L.A. County law enforcement officers, the process for reporting a domestic violence incident follows a certain protocol that can often become a deterrent for women to report.

When calls are made a report is taken after the responding deputies determine through their initial investigation who the dominant aggressor is, Diez said.

Most of the time, the accused party is the man in the relationship, he said. A 2021 study in the American Behavioral Scientist corroborated the idea, finding that approximately 75% of domestic violence incidents are perpetrated by men.

After the report is taken and statements are given, investigators look to see if the incident warrants a misdemeanor and felony violation. Once a suspect is arrested, SCV Sheriff’s Station deputies generally offer the victim an emergency protection order, which is an EPO, for 72 hours.

It is at this time that social workers, advocates and organizations begin to jump in to assist the survivor, finding out what they need to begin addressing their trauma and, ultimately, break the cycle, whether that’s emergency housing, connections to mental health resources or crisis response.

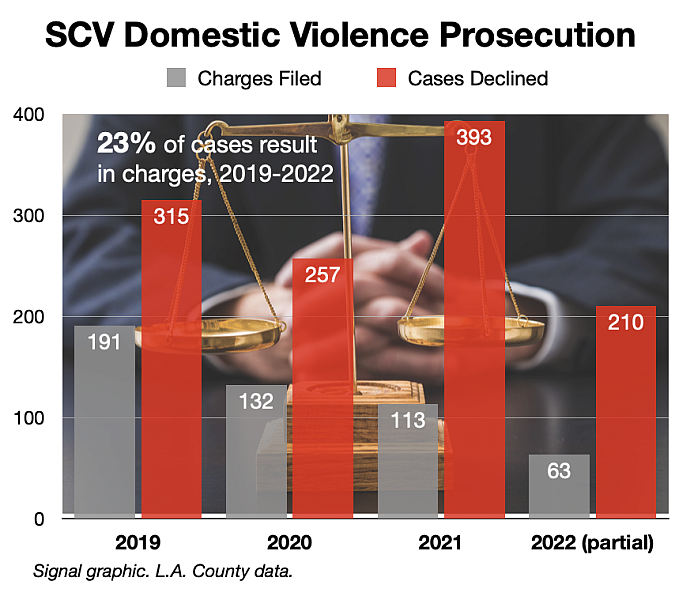

However, these steps often are not followed due to individuals not being properly made aware of the resources available to them, local advocates and law enforcement detectives agreed. And a Public Records Act request sent by The Signal to the L.A. County District Attorney’s Office shows that the Santa Clarita Valley cases filed by prosecutors dropped from 191 in 2019 to 132 in 2020.

“Our best practice for prevention has always been education,” said SCV Sheriff’s Station Detective Victoria Lambrech, “but it is hard because sometimes you have people that call and report and the case can’t be proven, and they feel very discouraged and they’re not going to report again.”

In an effort to combat the issue of people being unaware of the resources available to them, the SCV Sheriff’s Station, Child and Family Center and a host of other partners released the Divert Program. However, even this seems to not be enough in order to educate people far and wide locally, experts said.

In the end, Aschoff — who has been at the helm of the one of the SCV’s leading domestic violence resources for eight years — said the real issue is simple: “This is someone in a domestic violence situation and they don’t know how to get out.”

This article was produced as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 California Fellowship. Part 2 of 2. Part 1 appeared Oct. 15.

Resources for Victims

Domestic violence victims’ advocates identified the following organizations as providing resources — all of which are working to break down barriers for survivors:

Phone Numbers

• L.A. County Sheriff: 661-260-4000

• Henry Mayo Newhall Hospital Behavioral Health: 661-253‐8989

• Psychiatric Mobile Response Team (PMRT): 818-832‐2410

• Suicide Prevention Hotline: 800-273‐8255

• Crisis Text Line: Text “HOME” to 741741

• Domestic Violence Hotline: 661-259‐HELP (4357)

• Poison Control: 800-222‐1222

• Child & Family Center: 661-259‐8175

Websites

• Domestic Violence Program/Teen Violence Prevention Program of the Child & Family Center: www.childfamilycenter.org/services/domestic-violence

• Los Angeles County Domestic Violence Hotline:

dpss.lacounty.gov/en/jobs/gain/sss/domestic-violence.html

• Strong Hearts Native Helpline:

strongheartshelpline.org/abuse

• Strength United:

www.csun.edu/eisner-education/strength-united

• L.A. County Adult Protective Services:

wdacs.lacounty.gov/services/older-dependent-adult-services/adult-protective-services-aps

• RAINN (Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network):

• National Domestic Violence Hotline:

• Love is Respect:

[This article was originally published by The Signal.]