The Perfect Storm: How domestic violence escalated during COVID-19

This article was produced as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 California Fellowship.

Other articles include:

Shadow Pandemic: What can be learned from the pandemic’s domestic violence rates

Santa Clarita Valley Sheriff's Station deputies investigate a stabbing on Fir Court in Saugus on Thursday, April 15, 2021.

Tim Whyte/The Signal

Part 1 of 2.

On the morning of April 15, 2021, Michelle Dorsey awoke in her Saugus home like she would any other day. At 5 a.m., she turned off her alarm, crept downstairs so as to not wake her three boys sleeping in their rooms down the hall and walked into her kitchen to make her morning coffee.

In a house that was used to noise — with three boys who all needed help getting dressed and ready for school and their mom heading to work each morning — Dorsey could start her day with a few moments of stillness.

But that April morning, the tranquility was broken as Dorsey went downstairs to find her estranged husband, against whom she had a restraining order, waiting for her. (He would initially be arrested on suspicion of lying-in wait, in addition to a slew of other charges, including murder.)

He beat and stabbed her to death.

At 5:10 a.m., 9-1-1 dispatchers received a phone call from Dorsey, pleading for help immediately after the attack.

James Dorsey was found and captured, and pleaded guilty to murdering his wife. He received 35.5 years in prison, although current laws make him eligible for a parole hearing in just 20 years.

During her service, family and friends shared memories of Michelle Dorsey, who was remembered as an “amazing mother, daughter (and) sister,” for her “infectious laugh” and her love of the outdoors, animals, adventures and singing Disney songs.

Santa Clarita Valley Sheriff’s Station deputies investigate a stabbing on Fir Court in Saugus on Thursday, April 15, 2021. Austin Dave/For The Signal

Danielle Quemuel, a lifelong friend of Dorsey’s who has been helping the family in the aftermath of the tragedy, told The Signal that at the time of her death, Dorsey had been working her way through a separation from James and had filed for the restraining order.

In a statement she signed on Aug. 27, 2019 — nearly two years prior to her death — Dorsey stated she was “afraid that the violence would reoccur” when she gave her husband notice of the legal action.

Dorsey was one of many domestic violence victims who lost their lives during the COVID-19 pandemic, a time when advocates and law enforcement say many people were cut off from vital resources. A combination of increased substance abuse, a lack of shelter options and a backlogged court system made it difficult for victims to get timely help

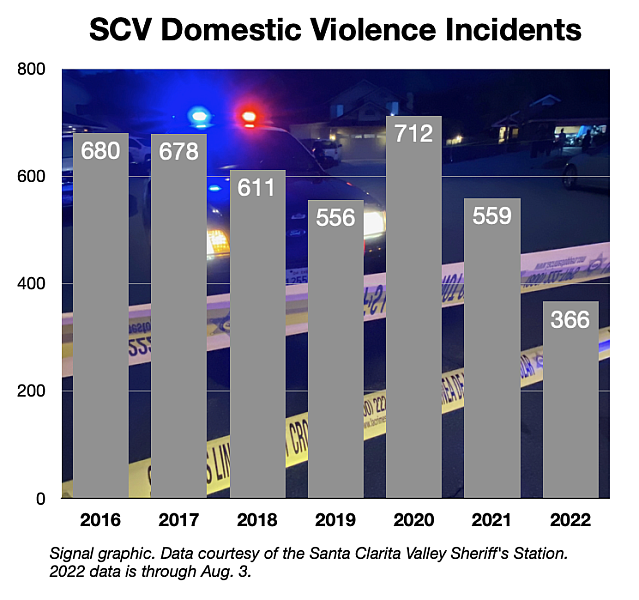

And there was a clear increase in incidents. According to statistics provided to The Signal by the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department, there were 712 domestic violence-related arrests in the Santa Clarita Valley for 2020 — a roughly 28% increase from the year prior. It’s the first time those numbers have breached 700 since 2016.

Additionally, in L.A. County as a whole — according to data available on the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department website — between the years 2020 and 2021, there were over 40 homicides at addresses where dispatchers had been previously called regarding a domestic violence incident.

Many victims were trapped with their abusers when lockdown orders came down. Even those who had freed themselves, like Dorsey, weren’t entirely safe, said Krysta Warfield, the program director of the domestic violence program at the Santa Clarita Valley Child & Family Center.

“The most dangerous time for a victim is when they leave or when they’re preparing to leave an abuser, so a restraining order can be necessary,” she said.

Even so, Warfield says violence can still occur after a restraining order is served, and “just leaving the situation” isn’t the end of domestic violence.

“A victim can do everything right; they can leave the situation, get a restraining order, but sometimes it’s not enough,” Warfield said. “This is a prime example of how ‘just leaving’ isn’t enough.”

The silent pandemic

Since Dorsey’s murder, similar stories of domestic violence during the pandemic would make headlines in the SCV and across Los Angeles County.

Despite a decrease in reported instances of crimes such as robbery and sexual assault, experts say the rise in domestic violence cases was inextricably tied to people being trapped in their homes with one another for months on end, the stress of the economy and the rising substance abuse issues at home.

“With the abusers working from home … the survivor doesn’t really have a break from the abuse, doesn’t have the ability to reach out to resources,” Warfield added. “And, ultimately, when law enforcement was getting the call, the calls were at a lot more heightened level than they were previously.”

In essence, the pandemic’s stay-at-home order forced families into economic hardship and cyclical substance abuse issues and left many domestic abuse victims without an escape.

In one L.A. County court case, a victim said she did not hear from anyone at L.A. County or nearby domestic violence centers for more than a year after she was found bloodied, locked inside a room with her daughter.

Although saying at the time of the initial incident that her husband, Dan Mortensen, had assaulted her, she and her teenage daughter would both later reverse their statements when on the stand in court — saying she had “fallen” after too many drinks that night.

In the first year of the pandemic, a Stevenson Ranch resident and Grammy-winning music producer, Noel “Detail” Fisher, would be arrested on suspicion of sexually assaulting more than a dozen women in his Stevenson Ranch home.

Another woman, who could not afford legal counseling because she was out of work as a result of the pandemic, would be told that her kids might be heading back to her abuser due to her not being able to financially support them.

“COVID was a form of power and control; it was used as a form of abuse,” Warfield said. “We had clients who were isolated being told that going out into the world meant bringing COVID back into the home and putting everyone at risk … it was used as a leverage tool.”

So, what appears to have gone wrong during the COVID-19 pandemic? How did it have such a negative impact on domestic violence? Were these problems the sole result of COVID-19 or did the pandemic reveal the cracks that were already there?

Domestic violence advocates say it was no surprise abuse skyrocketed during the height of the pandemic.

The perfect storm

Local experts say that the pandemic created a confluence of factors that led to a perfect storm for domestic violence survivors.

Substance abuse increased by as much as 13% nationally during the early months of the pandemic, according to the American Psychological Association. Law enforcement officials and domestic violence advocates agree this trend played a significant role in the increased violence at home.

“People started drinking a lot more during COVID, and a majority of our cases involve alcohol,” said Detective Victoria Lambrecht, a domestic violence detective at the Santa Clarita Valley Sheriff’s Station.

On top of the stress of being isolated with someone struggling with substance abuse, advocates say domestic violence victims had few places to turn for help, which resulted in repeat offenses.

“Law enforcement calls increased over 50%, but hotline calls dropped drastically,” said Warfield. “So, that showed that domestic violence was happening in the homes, but the access to resources was not available.”

Santa Clarita Valley Sheriff’s Station deputies investigate a stabbing on Fir Court in Saugus on Thursday, April 15, 2021. Austin Dave/For The Signal

Even the Santa Clarita Valley Child & Family Center had to shut down its domestic violence emergency shelter for a time at the height of the pandemic, said Joan Aschoff, the center’s president and CEO.

“It was a group dwelling, and we weren’t set up to be able to make sure that no one came in contact with each other,” she said.

Those emergency shelters only recently started to allow two families to be housed in one of their emergency shelters, Aschoff said.

To top it all off, the court system, along with almost all of the county’s legal bureaucracy, was brought to a near standstill in the initial months of the pandemic — making filing for court orders or restraining orders near impossible.

“Before, you could just walk into the court if you felt you were in danger and be able to file for a restraining order that same day,” Warfield said in 2021, “and that’s not typically happening now.”

As the pandemic wanes, advocates say domestic violence victims are reporting there’s still a pressing need to give victims the services and support they need, and to improve the system so additional tragedies can be prevented.

This article was produced as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 California Fellowship.

[This article was originally published by The Signal.]