Punishing Families Part 2: L.A. County Data Reveals Child Removal Hotspots

This story was originally published in California Health Report with support from our 2022 California Health Equity Impact Fund.

Photo by fizkes/iStock Photo

Last August, Princess Dale was invited to receive two certificates of appreciation from the city of Lancaster, for having co-founded the Antelope Valley’s inaugural Juneteenth Celebration.

It was a happy evening for Dale, as she accepted her awards and took photos with the elected officials.

But she also saw it as an opportunity to speak about another part of her life: the separation of her family.

Los Angeles County’s Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS) first removed Dale’s children in 2017, after she had a mental health crisis and tested positive for marijuana.

When it was Dale’s turn at the podium, she used her allotted two minutes to urge the Lancaster City Council and Mayor R. Rex Parris to investigate the practices at the two DCFS offices in the Antelope Valley, one of which had played a devastating role in her life.

“I’m begging you guys to please investigate the DCFS of Palmdale and Lancaster,” Dale said.

There were other parents at the city council meeting with similar stories, she said, gesturing at some of the women sitting in the audience behind her.

Dale told the council that she could get other mothers to write statements of their own experiences with the local DCFS offices. “I have so many women in my building whose children were taken,” Dale said. “They are literally ripping families apart.”

When Dale finished speaking, Councilmember Darrell Dorris, who had been nodding visibly as she spoke, backed Dale’s claims about the child welfare system in the Antelope Valley.

Dorris reminded the mayor that he had called to discuss the issue after a pastor at his church had his kids taken away.

“I know that what she’s saying is legit,” the councilmember said.

With liberal use of the catchall category of “general neglect,” LA County’s DCFS removes between 4,000 and 6,000 kids from their homes every year and places them in foster care. While there are extreme circumstances when out-of-home placements are needed, far too many LA County kids are taken from their parents because of inequities in the child protective services system and society at large. Social workers place children of color and those who live in the lowest-income communities in foster care at higher rates than their peers in wealthier, whiter neighborhoods.

The problem, said Parris, Lancaster’s mayor, is that when social workers fail to protect a child from harm, “that’s front page news.”

In contrast, he said, “it’s not front-page news when they take people’s children needlessly.” It’s not clear why DCFS can’t seem to get it right, said Parris, “but it creates an enormous number of attachment disorders that end up in our criminal justice system.”

Princess Dale addresses the Lancaster City Council on August, 23, 2022

Photo courtesy of Witness L.A.

A catchall category

In 2022, 134,940 children were referred to LA County’s Department of Children and Family Services.

The referral numbers are slightly complicated by the fact that a child can be counted more than once if, say, a neighbor and a teacher each report that they suspect the kid is being mistreated or neglected.

Approximately 34.3% of the nearly 135,000 referred children were suspected of experiencing conditions of “general neglect.”

In Part One of this series, we explained how, using this particular category, DCFS takes children from parents who use drugs — including marijuana in some instances —from parents experiencing mental illness, from parents who are victims of domestic violence, and from those unable to provide adequate food, supervision, or other necessities.

By contrast, “severe neglect” — when parents are accused of intentionally failing to provide necessities for their children in ways that endanger their kids’ health — made up just 1.1% of cases in 2022.

In 2021, mandated reporters and other concerned individuals referred kids in LA County communities to DCFS 47,895 times for conditions falling into the category of general neglect.

In response to Dale’s statement at the August meeting, Mayor Parris said he had hoped that the situation would change when, in 2017, the LA County Board of Supervisors hired now-former DCFS Director Bobby Cagle.

“I was impressed with him. I met with him,” Parris said. It looked like Cagle would bring change to the department. “And then he quit.”

Before Cagle’s arrival, social workers’ inaction led to the high-profile death of Gabriel Fernandez. The eight-year-old was tortured and fatally beaten in 2013, by his mother and her boyfriend in Palmdale, despite numerous reports to the DCFS indicating the boy was being abused.

Yet, during Cagle’s four-year tenure, two more little boys died violently in the care of their parents in the Antelope Valley, ten-year-old Anthony Avalos in 2018, and four-year-old Noah Cuatro in 2019. These deaths reignited public outrage at the Department of Children and Family Services and demands for social workers to better protect children.

The deaths were also an incentive for social workers to err on the side of removing kids unnecessarily, to protect kids from dying — but also to protect the department from media scrutiny and social workers themselves from discipline or criminal charges.

“I can’t begin to tell you the number of people that have come to me with horror stories,” Parris said, referring to parents who believe their children have been unfairly taken away.

Taking kids of color

In LA County, data WitnessLA obtained from DCFS shows that Black families are investigated for allegations of general neglect and removed from their homes at rates greatly disproportionate to their share of the general population. An analysis of the county’s data also shows that families living in low-income zip codes are far more likely than families in wealthier zip codes to experience child welfare referrals and removals.

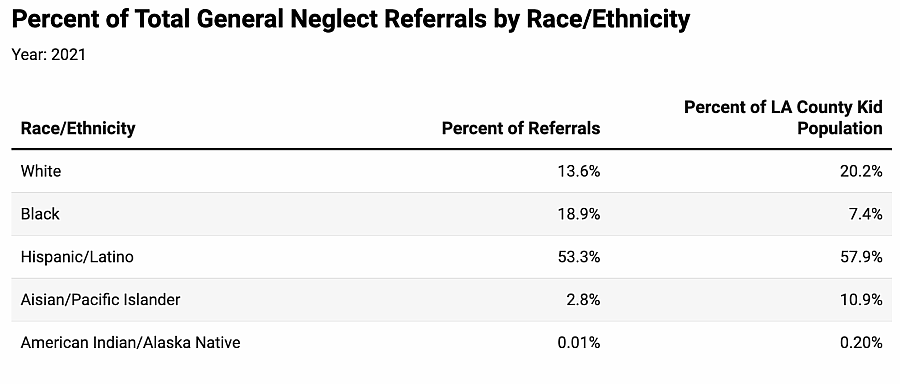

While Black children make up just 7.4% of the county’s youth population, between 2018 and 2021, 18.3% to 19% of all general neglect referrals concerned Black kids.

At the same time, white children account for 20.2% of the local kid population, and 12% to 13.6% of kids referred to DCFS for general neglect during those years.

Interestingly, Hispanic/Latino kids, who account for 57.9% of LA County’s children, made up 52.9 to 58% of referrals. Asian/Pacific Islander kids make up 10.9% of the population and accounted for 2.5 to 2.8% of referrals. American Indian/Alaska Native kids — 0.2% of the population — made up .01 to .016% of referrals, according to the county’s data.

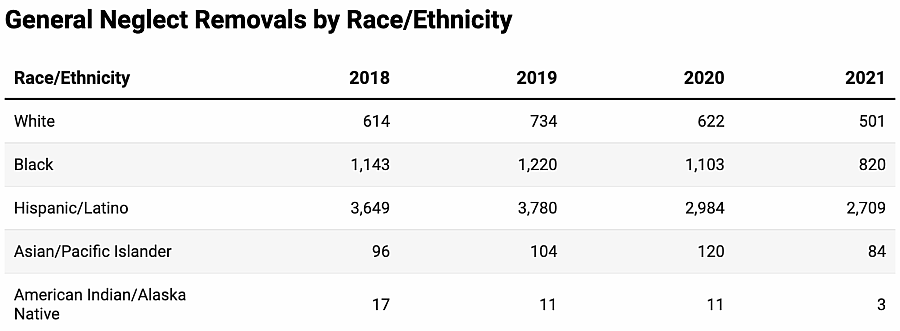

Black children were also more likely than white children to be removed from their families for the designation of neglect.

Between 2018 and 2021, DCFS removed nearly double the number of Black children as white children for neglect.

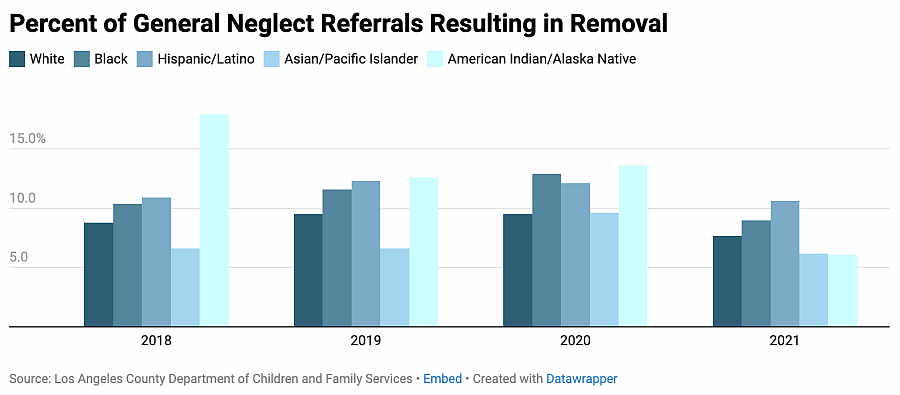

Once referred to DCFS, Black and brown kids are generally more likely to be taken from their families than white and Asian kids.

Between 2018 and 2021, social workers removed between 9% and 13% of Black kids suspected of experiencing neglect, while removing just 6% to 9.5% of their white peers.

In three of those same four years, kids identified as Hispanic/Latino and American Indian/Alaska Native were each more likely than white, Black, and Asian/Pacific Islander kids to be removed from their homes after a referral.

It’s worth noting that while Native American/Alaska Native kids are often severely overrepresented in child welfare systems nationwide, during the four year period of 2018 to 2021 in LA County, the percentages of American Indian/Alaska Native kids removed shows curious inconsistencies, which are due, at least in part, to a far smaller sample size compared to the other race/ethnicity categories.

The poverty connection

In addition to the racial disproportionality, our analysis of county data revealed that the probability that kids will come into contact with DCFS is much higher in certain LA County communities.

When we compared local child welfare data with median income data from the census, we found that kids from the county’s 68 lowest-income zip codes were far more likely than kids from wealthier zip codes to be reported to DCFS and to later be removed from their homes.

To analyze this data, we broke the county’s inhabited zip codes into four equal groups of 68 — lowest median income, lower median income, higher median income, and highest median income. (We excluded certain zip codes, including those that were strictly commercial.)

Within the lowest income grouping were zip codes in and around South LA, Long Beach, Compton, the Antelope Valley, East Hollywood, and parts of the San Fernando Valley. The most affluent zip codes included Beverly Hills, Calabasas, Thousand Oaks, parts of Pasadena, Santa Clarita and beach communities like Malibu, Santa Monica, and Rancho Palos Verdes.

The lower-income zip codes also averaged higher percentages of Black residents and smaller percentages of white residents than the wealthier zip codes.

WitnessLA found that kids in the lowest income communities — where annual median earnings land between $22,000 and $62,000 — were far more likely than the other three zip code groupings to be referred to DCFS and to be removed from their homes.

In 2021, those in the lowest income zip codes, where an average of 21.6% of people live below the poverty line, were 3.7 times more likely to experience DCFS referrals than kids in the wealthiest zip codes where median earnings ranged from $100,000 to $212,000 and just 6.2 percent of residents live below the poverty line.

In the wake of a referral, kids in poorer parts of the county were more likely to be removed from their homes than kids referred to DCFS in rich areas.

In the lowest-income communities, an average of 8.9 percent of referrals resulted in removal, while an average of 6.1 percent of referrals in the wealthiest neighborhoods led to removal.

In other words, approximately 89 kids out of every 1,000 referred to DCFS in the poorest zip codes were taken from their families, while 61 out of every 1,000 referred kids were removed in the wealthiest areas.

For two communities in the South Bay — one wealthy, one poor — the differences are even more conspicuous.

The zip codes making up the affluent Palos Verdes Peninsula, just west of Wilmington and San Pedro, are among the ten wealthiest zip codes in LA County.

In 90275 and 90274 — Rancho Palos Verdes, Rolling Hills Estates, and Palos Verdes Estates — where approximately 67,000 people live, there were a total of 65 referrals to DCFS in 2021. No children were removed.

Just east of the peninsula, in Wilmington, one of the lowest income areas with a population of just over 57,000, 403 children were referred to DCFS. Of those, 43 kids were removed.

The five zip codes with the worst numbers

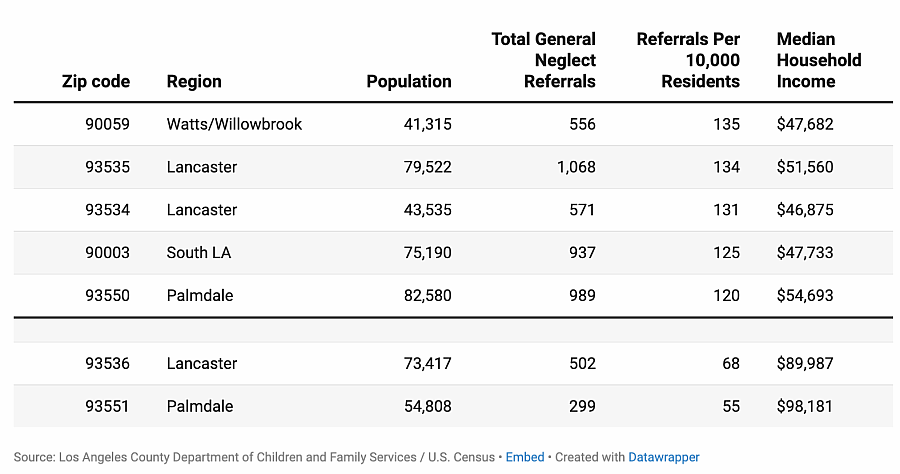

We also took a closer look at the five zip codes with the highest per-capita general neglect referral numbers (and populations over 10,000). Each was listed among the 68 lowest-income zip codes.

Two of the five zip codes were in South LA and Watts/Willowbrook. The other three were located in the Antelope Valley, where Princess Dale and Lacie, whose story also appeared earlier in this series, both live. (“Lacie,” if you remember, is a pseudonym.)

These five areas had between 120 and 135 referrals per 10,000 residents in 2021, compared with the average per capita rate of 38.7 referrals across all LA County zip codes, and an average of 17.8 referrals per capita in the 68 wealthiest communities.

While parts of Lancaster and Palmdale accounted for three of the zip codes with the highest referral rates, two zip codes right next door – 93536 in Lancaster, and 93551 in Palmdale — had starkly different referral rates.

In the 93536 area of Lancaster, there were just over half the referrals per capita — 68.38 — as 93535 and 93534, the other two high-referral Lancaster zip codes.

Next door, in 93551, there were 54.55 referrals per capita.

One notable difference between these lower referral zip codes and the three adjacent areas where families were far more likely to come into contact with DCFS, was that median incomes were close to double that of each of the three neighboring zip codes.

Similar patterns emerged in zip codes sharing borders within other cities, such as San Pedro and Long Beach.

An unexpected separation

In the Antelope Valley, Lacie said she was a victim of the change to err on the side of removing children.

In 2020, after her son’s teacher reported Lacie’s family to DCFS for domestic violence, investigating social workers told Lacie she would need to take a drug test. The results showed that Lacie had drugs in her system. Unlike in the case of Princess Dale, social workers left the kids in Lacie’s custody.

Three weeks later, her social worker surprised Lacie when she announced DCFS would be taking her children, after all.

Lacie asked for an explanation. Why, she asked, if DCFS believed the children were unsafe, did social workers not remove them immediately?

The social worker told her that while they were not going to take her kids initially, they ultimately did so because a little boy had died in Lancaster after social workers neglected to remove him.

Parris, the Lancaster mayor, said he feels for the parents in his town who have had their children removed. If someone had taken his own children, the father of four said, “I’d have lost my mind.”

This is the second in a multi-part series about racial and economic disparities in Los Angeles County’s child welfare system, and the impact family surveillance and separation has on kids and their parents.