Public transit fails its mission in the Bayview

This story is part of a series produced by Carly Graf, a participant in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2021 California Fellowship.

Her other stories include:

Vaccines increase as Bayview-Hunters Point battles Delta surge

Is Golden Gate Park really for all San Franciscans?

San Francisco’s Bayview district struggles to emerge from food desert

How San Francisco’s Bayview neighborhood is battling toxic air

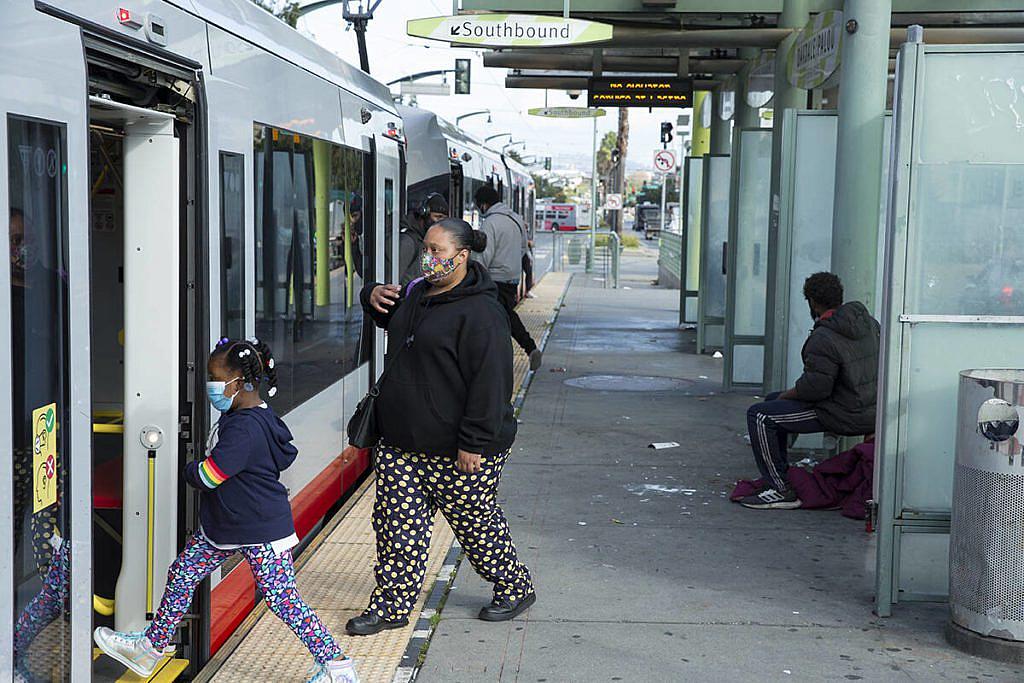

Passengers board a T-Third Street Muni train bound for Sunnydale at the Oakdale/Palou station in the Bayview District.

(Kevin N. Hume/The Examiner)

Despite San Francisco’s transit-first policy — designed to ensure public transportation effectively serves and connects neighborhoods — entire swaths of The City remain isolated, cut off from even basic necessities like food and healthcare.

And nowhere is that more true than in the Bayview.

“You really are a second-class citizen in San Francisco” if you live in the neighborhood, said Monique LeSarre, executive director of the Rafiki Coalition for Health and Wellness. “Transportation has improved a little bit, but overall you can’t get anywhere from out here easily and fast.”

Buttressed by Highway 101 on its western edge and a stretch of land zoned for manufacturing facilities, the Bayview is largely cut off from the rest of San Francisco. It also happens to be one of The City’s poorest neighborhoods where residents face persistently high rates of chronic illnesses such as asthma, diabetes, cardiovascular disease and high blood pressure.

Many who know the neighborhood well will tell you that confluence is not a coincidence.

“It was predominantly a Black community historically, and we have not treated Black people with the same dignity and respect as others,” said LySlynn Lacoste, executive director of BMAGIC, a community nonprofit. “I think it ultimately comes down to that. It’s really simple.”

Nearly 70% of residents were Black in 1980. That number has since dropped to about 27%. Today, over half the neighborhood is composed of Latino, Asian and Pacific Islander residents.

Advocates have long recognized the direct line from divestment in vital infrastructure such as transportation and the sustained struggles residents have had to endure when they can’t readily access food, job opportunity and education.

The T-Third Muni Metro line, opened in 2007, was supposed to remedy some of this geographic isolation by linking up the easternmost neighborhoods with downtown. But it quickly built a reputation of delays, unreliability and infrequency so bad that residents began calling for the restoration of the Muni bus line that the 5.5-mile light rail route had replaced.

The San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (SFMTA) finally heeded that call in January 2021 with the creation of a temporary bus route to directly and quickly connect Bayview and Hunters Point residents, many of whom are essential workers, with essential workplaces downtown.

At the time, District 10 Supervisor Shamann Walton called the route a key step in “repairing the harm that has been done to Black, brown and Asian communities.”

A 15-Bayview Express Muni bus turns onto Third Street from Palou Avenue. The new bus route was created in early 2021 in response to advocate criticisms of the reliability of the T-Third line in connecting residents with essential jobs and services downtown. (Kevin N. Hume/The Examiner)

The 15-Bayview Hunters Point Express route will run into 2022, and future updates will be considered as part of ongoing discussions about citywide service, according to Stephen Chun, SFMTA spokesperson.

Difficulty traveling by transit isn’t limited to trips within San Francisco borders. Reaching regional destinations is cumbersome, too. The neighborhood lost its only Caltrain station in 2005 due to low ridership — though The City has recently begun outreach on plans to build a replacement — and the nearest BART station is across the highway.

Impact of isolation

The lack of a transit service would be less of an issue if Bayview residents had much of what they needed nearby. Urbanists often wax poetic about the 15-minute city vision in which everything a person needs is easily accessible by foot or by bike.

That’s not even remotely the case in the far-flung southeastern corner of San Francisco.

Most people must travel to workplaces, grocery stores, pharmacies, child care facilities and other vital services outside the neighborhood.

The impacts of this isolation aren’t abstract. They’re felt every day by residents who face poor health outcomes directly tied to their environment. The 94124 ZIP code, which includes the Bayview and Hunters Point neighborhoods, has the greatest rate of preventable emergency room visits due to heart failure, diabetes and hypertension, according to a 2019 report from UCSF.

Passengers aboard a T-Third Street Muni train bound for downtown. (Kevin N. Hume/The Examiner)

“Improving health outcomes requires us to focus our attention on patients’ lives both inside and outside of the doctor’s office,” the same report reads. “Improving health outcomes requires removing obstacles to good health, including the impediments of poverty and discrimination, which are associated with reduced access to jobs with fair pay, education, housing, safe environments, and health care.”

Unfriendly terrain

Over 30% of Bayview households earn less than $30,000 annually, according to SFMTA-provided data, yet almost half of all households own two or more cars, double the citywide rate. Nearly 51% of commuters drive to work compared with 35% citywide.

High rates of car ownership can’t be written off as bad personal choices but rather the “geographic isolation of the community and the level of transit service,” according to the SFMTA’s own Bayview Community-Based Transportation Plan, designed to improve mobility options in the neighborhood.

The same report acknowledged travel by foot or by bike is hardly a viable alternative and The City’s responsibility to remedy the situation.

It describes a neighborhood reality that is anathema to urban planners: streets “defined by their irregularity;” connectivity that depends on “a circuitous and poorly connected street grid with frequent dead-ends;” and streets connecting the Bayview to the rest of The City “traveling through industrial areas unfriendly to walking and biking trips.”

For those who dare to navigate this situation, they’ll find “broad but underutilized” streets with “travel lanes 50% wider than a standard freeway lane” that “facilitate speeding and reckless driving.”

This situation doesn’t just put the Bayview at a disadvantage when it comes to connections with vital services and opportunities, it discourages residents from embracing physical movement like walking or biking — basic ways to promote health.

According to the 2019 Community Health Needs Assessment from the San Francisco Department of Public Health (DPH), just two and a half hours of moderate intensity aerobic physical activity every week — such as walking or biking — is associated with three or more years of life. That’s especially meaningful when you consider that the average Black San Franciscan’s life expectancy is 71 years, 10 years shorter than that of a white resident.

Path forward

Even DPH calls transportation a “powerful mediator of access to health — from health care to food to social connections.”

TransitCenter, a New York-based nonprofit that studies cities, concluded transit in the San Francisco-Oakland region provides less access to opportunities for residents of color than it does to white residents. It also found longer trip times make it easier — and often more affordable — for people to take private automobiles over public transportation.

The nonprofit recommends a number of general interventions to make transit more equitable, some of which SFMTA has adopted such as providing an analysis of how the system serves various communities available during public meetings; expanding transit-only travel lanes; and exploring how express routes can serve neighborhoods with historically under-performing buses and trains.

SFMTA’s approval of the Bayview Community-Based Transportation Plan in February 2020 marked its boldest step to right some of the wrongs wrought by redlining and redevelopment, many of which left the neighborhood isolated from the wealth, resources and opportunity of The City.

The agency worked much more closely with community-based organizations and grassroots groups than it had in the past, helping to gain the trust of residents who vocalized concerns and priorities.

Together, SFMTA and the community laid out 101 projects to be completed in the plan. Of those, SFMTA has completed more than half of the 53 highest priority items including staffing three transit assistants on Muni lines and rolling out pedestrian safety improvements on Hunters Point Boulevard. Similar efforts underway on Williams and Evans avenues.

All told, the proposals call for $8.6 million aimed at improving the performance of the T-Third line, which has the lowest on-time metrics of all SFMTA rail lines, according to agency data, and promoting frequent, reliable bus transit.

It also endeavors to make biking and walking more viable modes of transit. Next year, SFMTA will launch a process to develop a citywide bike plan, the first of its kind since 2009, Chun said. Working with community partners, SFMTA hopes to identify and mitigate barriers that might deter people from bicycling, including gentrification, cultural and policing concerns.

Though many acknowledge the progress being made, skepticism that The City will drag its feet on living up to its promises is likely to remain pervasive after decades of being told to wait their turn for the same basic necessities that so many other neighborhoods enjoy.

Carly Graf wrote this story while participating in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2021 California Fellowship.

[This article was originally published by San Francisco Examiner.]