As Omicron Variant Emerges, Issues With Porta-Potties and Sinks For Homeless Persist Despite L.A.’s Intent To Do Better

This is part six of a 20-month long investigation looking into hygiene stations that the City of Los Angeles distributed to homeless encampments. This project was produced for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2020 Data Fellowship. Start from the beginning here.

His other stories include:

Part 2: There Weren't Enough Porta-Potties For The Homeless To Begin With, In October They're Being Pulled

Part 5: City Reverses Decision to Remove Washing Stations from Encampments Following L.A. Taco Investigation

Portable sink in Skid Row missing soap dispenser surrounded by trash

L.A. TACO

When the pandemic first hit, the City of Los Angeles raced to roll out hundreds of portable sinks and toilets to the tens of thousands of people living on the streets. But they didn’t have much of a plan to ensure that those units were maintained properly or protected from vandalism. After a 14 month, long L.A. TACO investigation revealed that vendors were getting paid millions of dollars for work they weren’t completing, the city once again sprung to action. Only this time they decided to remove all of the units.

“Whoa. What happened?” A representative from United Site Services (USS), the largest provider of portable sinks and bathrooms to the city, wrote in a late-June email after receiving an unexpected request to remove hundreds of units just days before the start of a new billing cycle. According to emails obtained by L.A. TACO through a public records request.

“I thought this was going to be long term for the homeless situation,” the USS employee wrote.

After collecting more than $4 million in fees, the rug was pulled out from under them. “I’m sorry, I do not have any info on how this was determined,” a city employee explained after breaking the news. The following week, USS began removing hundreds of portable sinks and toilets, just as the Delta variant became the most dominant coronavirus strain in California.

Then, about a month later, following additional reporting from L.A. TACO revealed that city representatives were also blindsided by the decision and in light of the emerging Delta variant, City Councilmember Mark Ridley-Thomas championed a motion to bring back up to 150 sinks and toilets.

After a contentious election, Ridley-Thomas emerged as an outspoken leader on homelessness earlier this year. The former county supervisor began his term by co-authoring a controversial proposal to allow the city to ban sitting, lying, or storing personal property in certain areas if the city is able to offer people living on the streets interim shelter or housing. Shortly after the proposal was signed into law, Ridley-Thomas began pushing for hygiene stations.

“How can people use the sink on the street if they’re in jail for sleeping on the sidewalk? No, we did not forget that you authored 41.18 Mark Ridley-Thomas,” an organizer with the homeless advocacy group Street Watch LA, told L.A. TACO in August.

Two months later, a federal indictment revealed that Ridley-Thomas allegedly accepted bribes before he was elected to the city council, resulting in cries heard from city hall to South Central where Ridley-Thomas grew up. Days later, the city council voted to suspend the career politician and the city controller revoked his more than $200,000 a year salary, raising fresh concerns about the council member’s ability to represent his district as well as take on important issues like homelessness.

Questions directed to a Ridley-Thomas spokesperson for this story were referred to Mayor Eric Garcetti’s office.

The motion to reinstate a fraction of the hygiene stations was ultimately approved unanimously by the city council in mid-August. And although 150 units were nowhere near the roughly 500 that were distributed during the initial rollout, unhoused residents and advocates generally welcomed the much-needed restrooms. After all, Los Angeles, a city of nearly four million residents, is notoriously short on public bathrooms.

Over the past five months, we reviewed hundreds of emails, purchase orders, contracts, and assessment records in an effort to gain a better understanding of why the hygiene station program fell apart so abruptly and how city leaders attempted to build it back up again. Here’s what we found.

The second rollout of hygiene stations was slow.

The city essentially had to start from scratch, so in mid-August, the mayor’s office began working with individual council offices to determine where each unit should go. Funding was approved by the city council in early August but the first wave of portable sinks and toilets didn’t hit city sidewalks until late September, according to Garcetti’s office.

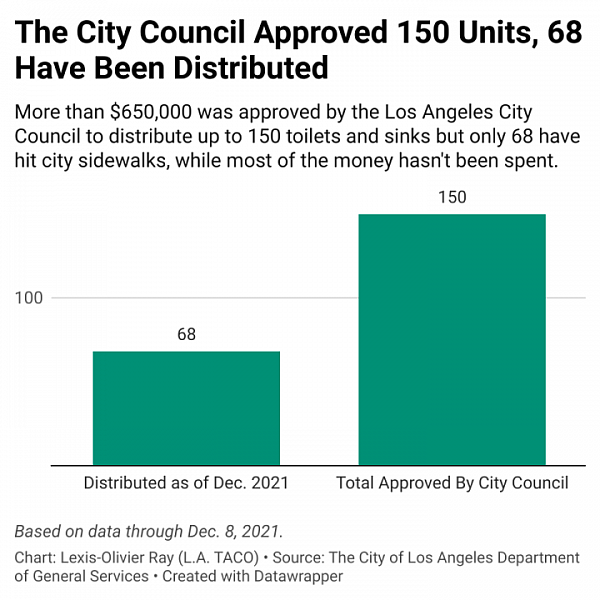

As of mid-December, there were only 68 portable toilets and sinks available. Nowhere near the 150 that the city council approved, a number that was already disappointing to some critics.

Harrison Wollman, a spokesperson for Mayor Eric Garcetti blamed the deficit on “an unanticipated increase in service costs, as well as a fluctuating number of repairs and replacements for missing or damaged units.”

Ultimately, removing hundreds of sinks and toilets, only to replace them weeks later ended up costing the city more money. According to contracts provided by the Department of General Services, reviewed by L.A. TACO, during the initial rollout back in March 2020, the city paid United Site Services (USS) $11 per service. Now they’re paying slightly more than $38, nearly four times the previous amount.

There is still plenty of money on the table though. More than $650,000 was allocated for the units and as of the most recent billing cycle (Oct 31), the city has spent less than $45,000 on them. Wollman says the rest of the money will go towards the bathrooms and sinks “until the funding is depleted.”

In addition to rising costs, some council districts were reluctant to participate in the program again. Ultimately, two council offices refused to bring back a single bathroom or portable sink to their respective districts, despite the desperate need for public restrooms and growing concerns from health officials over COVID variants.

On top of all that, it appears that some units continue to suffer from maintenance issues that we’ve previously reported on, such as broken soap dispensers, sinks with no soap and/or water, and unusable bathrooms.

Portable sink in Skid Row missing soap dispenser and water.

SAME OLD PROBLEMS

It’s a sunny but brisk December day in L.A. and Kemoney, a former truck driver who currently lives on the streets, is surprised to see a clean porta-potty in Skid Row. “Normally that shit be nasty, be dirty, be filthy. And usually, people spend like three or four hours in there, so it’s hard to use one. But today it was free. It was available. It was clean. So I was surprised.”

One problem though. “Somebody took the time to clean it out, but they didn’t take the time to put no water and no soap in there,” Kemoney told L.A. TACO during an interview.

Kemoney doesn’t use this outdoor restroom every day but when he does, he says the unit is ordinarily unusable. “I’ve seen the water in that thing…maybe two times in the last two months, two months ago. But I don’t be using it all the time,” Kemoney says, referring to the portable sink.

“Somebody is paying for [soap and water] to be here, but it’s not there.”

He describes the situation as, “like an oxymoron.” “You put out a restroom and you put a handwashing sanitation center out here. But yet it’s not available all the time because it’s not being maintained.”

Kemoney suggests the city pay for a “janitor” to service the units regularly. He thinks that unhoused residents like himself or possibly volunteers could even play a role in helping to maintain them.

Greg, an unhoused man living in a tent near Little Tokyo agrees. Similar to Skid Row, the two portable sinks near him are both completely dry. He says that someone generally comes to service them every day or so. But they don’t always show up or do a thorough job. “Sometimes they don’t leave paper towels,” says Greg.

Portable sink and toilets in Little Tokyo.

Last week, L.A. TACO assessed the soap, water, and paper towel levels at six different locations in DTLA

Only one location was fully stocked with materials. The rest of the units had no soap or water, were tagged with graffiti, and in some cases missing soap dispensers and covered with flies. An L.A. TACO review of assessment records indicates that some units went multiple days without being serviced.

This is eerily similar to the situation earlier in the pandemic, when vendors were getting paid millions of dollars for work they were not completing, only this time, there’s less money involved.

Harrison Wollman, the Garcetti spokesperson, told L.A. TACO that “every unit is serviced daily.” Wollman added that “units are often moved from their initial location” which prevents vendors from providing service. “There are also situations where a separate contractor is required to fix specific issues that arise.” A needle in a water tank for instance can take multiple days to address. According to city records obtained by L.A. TACO, nearly 30 percent of the money spent on the program has gone towards replacing units and “decontamination services.”

Another reason it’s not uncommon to see filthy, unusable portable sinks and toilets in neighborhoods like Skid Row is that when vendors were asked to remove all units this past summer, they inadvertently left some behind. Under the new contract, those units don’t get serviced anymore. They just sit on the sidewalks. This can be confusing because they look the same as units that are in service.

After being presented with our findings, Pete Brown, a spokesperson for Councilmember Kevin de León, the council representative for Little Tokyo and parts of Skid Row, told L.A. TACO in a statement: “When the council office received complaints about maintenance issues at hygiene stations, Councilmember de Leon took action to submit a motion for a citywide public restroom system that works and doesn’t rely on porta-potties for our unhoused neighbors and pedestrians, especially along our commercial corridors. Council District 14 takes these concerns seriously and is actively pushing for reforms that provide substantive improvements to outdoor hygiene and restroom stations.”

Greg, the unhoused man in Little Tokyo, is adamant that public bathrooms need to come with attendants. Otherwise, they deteriorate.

“It’s like self-sabotage,” he says.