Special report on opioid crisis in Oakland’s unhoused community: Voices of overdose and survival

This special report is part of a reporting series by Ariel Boone for Street Spirit and KPFA Radio with a USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism 2021 California Fellowship.

Her others stories include:

Part 1: Opioid Overdoses Are At Record Highs. It Doesn't Have To Be This Way.

Part 2: Alameda County Doesn't Track Deaths of Unhoused People - Here's Why that Impacts the Opioid Crisis

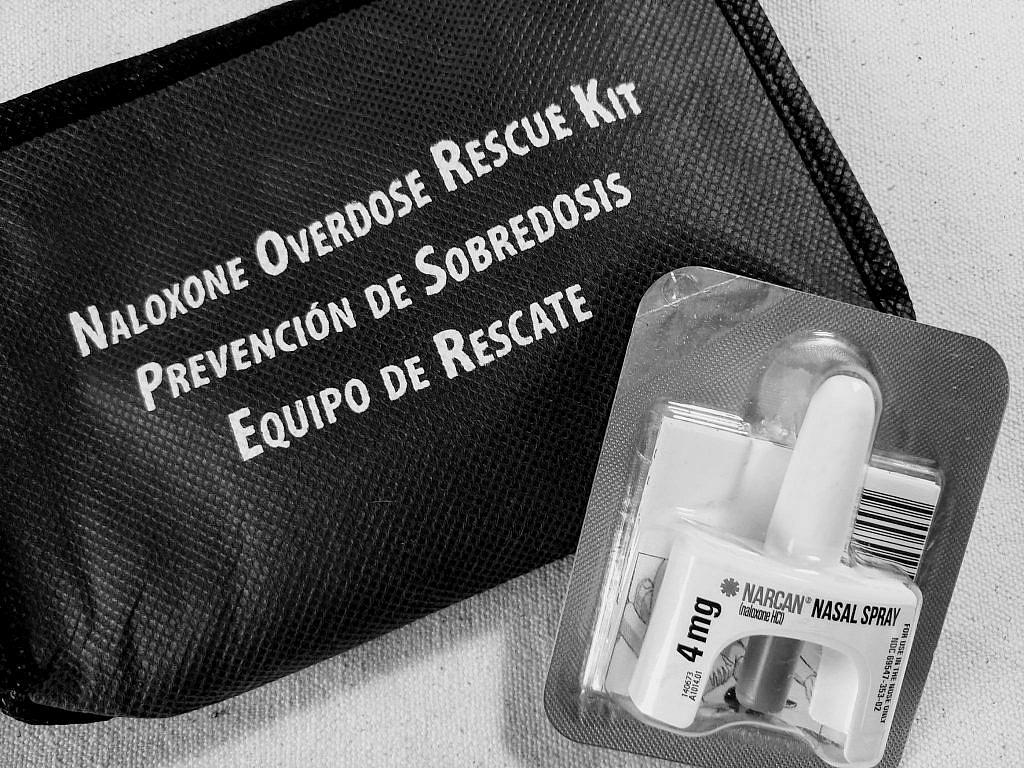

Nasal spray Narcan, used to reverse opioid overdoses

Lucy Kang

OAKLAND, CA — Thad is 36 years old and was born in Berkeley. He’s got brown hair just past his ears, and when we meet, he’s wearing a yellow and green snapback hat, with some designs he’s drawn on by hand. He’s living in an encampment next to a freeway in Oakland. And he’s one of thousands of unhoused people who deal with substance use in Alameda County.

“Fentanyl is a weird drug to do because it’s literally just kind of like straddling death. It’s the end of the road,” he tells me. Thad uses fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid. “It’s just, for fentanyl users, kind of like tiptoeing or tightrope-walking to death to get high.”

“I’ve overdosed three times in the last year to where I had to be Narcanned back to life,” says Thad. “I probably would have died, for sure, just from inhaling a little bit of smoke. It’s crazy.”

Thad has survived three overdoses since the pandemic started. The people he was with carry Narcan, the overdose reversal drug. And that’s why he’s alive.

In Alameda County, nearly one person dies every day from some kind of overdose. In 2020, about half of those deaths involved opioids.

But here in the East Bay, we still don’t know the real extent of the loss. After 16 months of reporting, I learned that there are huge gaps in our understanding about the opioid crisis in Alameda County’s unhoused community, and that ultimately, unhoused people are saving the most lives for each other during this emergency – by reversing overdoses on trains, in tents, under freeway overpasses, wherever they live, every week, by the dozens.

A closer look at fentanyl

Behind most of those overdoses is a pharmaceutical drug called fentanyl – the one that Thad uses. Seth Gomez, senior pharmacist for Alameda County Healthcare for the Homeless, says he thinks fentanyl “absolutely” has a role in the overdose crisis. In 2020, fentanyl made up 81% of opioid overdose deaths in the county.

Fentanyl is a powerful synthetic opioid. A clinician might prescribe it to you in a hospital after a surgery to treat severe pain. But the street supply is made in illicit labs. It can be around 40 times more potent than heroin.

Even as fentanyl proliferates in the drug supply, some people do choose to use it. I spoke to one Oakland resident named Kory about why he uses fentanyl.

“I got tired of using needles and never being able to hit myself,” Kory tells me. “If I were to try smoking heroin, that’s not fulfilling at all. But when I smoke fentanyl, I actually feel it. I have a high tolerance because I’ve been using for so long, and it’s just — the needles thing has become just a nightmare, when you don’t have veins and you’re trying to hit yourself.”

There’s a widespread image circulated by police departments that shows equivalent potent doses of heroin, fentanyl, and carfentanil, a relative of fentanyl that’s even more potent.

Widely-shared images of opioids show their relative potency — fentanyl and its analogs, which are proliferating in the West Coast drug supply, are far more potent than heroin.

There are three vials in the photo. In the heroin vial, there’s what looks like a half a teaspoon of salt. In the fentanyl vial, there’s what looks like maybe 50 grains of salt. And in the carfentanil vial – there’s maybe 4 grains of salt. The message is: it takes a lot less fentanyl, or carfentanil, to get you high – or cause an overdose.

The first time Thad overdosed, it was only the second or third time he had smoked fentanyl.

“For first time users, when you first start using, you’re going to overdose, just because it just takes only a little bit, and it goes from that high to death,” Thad says.

He’s pretty sure he overdosed all three times because he mixed fentanyl and alcohol. He feels a responsibility to the people who use drugs around him, too.

“I really try not to even do fentanyl with people who don’t do it, or are just starting to do it. I just don’t even really want to be around for that, you know? I want to kind of be aware, because I don’t want to nod off and wake up to someone dead.”

The pandemic has been especially deadly for opioid users like Thad. The CDC has provisionally reported nearly 70,000 fatal opioid overdoses in the US in 2020 – a 35% increase over 2019 and the most ever in this country.

In Alameda County, the overdose numbers have gone up dramatically during the pandemic. If you look at a 12-month graph of overdose rates, starting at the end of 2019, the line just spikes higher, and higher and higher. The victims tend to be men, in their mid twenties to fifties.

But what exactly is an overdose?

Basically, it’s when the physical effects of a drug overwhelm the body’s ability to keep itself alive – in the case of opioids, a person’s breathing becomes shallow and slow, or stops completely. Oxygen levels drop dangerously, and you can die.

But there’s a simple way to reverse this process: Naloxone, also known as Narcan.

“The way an EpiPen [epinephrine injection] is used for somebody with a severe allergic reaction or anaphylaxis – basically Naloxone is our Epipen for an opioid related overdose,” says Seth Gomez from Alameda County Healthcare for the Homeless.

There is a short window of time after someone takes a fatal dose of opioids where naloxone can revive a person. It comes in two forms. One is injectable, and the other is a nasal spray, about the size of a pack of floss. The medication immediately puts you into withdrawal. It’s called an antagonist, meaning it kicks out all the opioids from receptors in your brain and takes their place for 30 to 90 minutes – long enough for you to start breathing again.

That’s called an overdose reversal. But the experience of being revived by Narcan can be deeply unpleasant.

“By giving them the naloxone, we are allowing that person to breathe again, temporarily,” says Gomez. “But in order to accept that, we also have to accept that there’s a chance that there are these other effects that Naloxone can trigger. These are effects that somebody would experience any way if they spontaneously went without their opioids for a period of time. But Naloxone basically jumpstarts that time and has people experiencing them much sooner.”

The first time Thad overdosed last year, the woman he was smoking with administered Narcan nasal spray. “When you come back from it, I didn’t even know what was going on,” he remembers. “And it immediately makes you super dope sick where your stomach is sick, and your body hurts.”

Once a person receives naloxone during an overdose, they now have all the typical opioid withdrawal symptoms at once: nausea, diarrhea, light sensitivity, pain. You feel really, really awful.

When Thad got up and tried to walk around, he was overcome by nausea and threw up in a port-a-potty. He had to lie down to ride out the withdrawal sickness.

“It was kind of scary afterwards to think about because I’d seen it happen to other people,” Thad reflects. “To go through it the first time was messed up. And then afterwards, the second time and third time, I just felt stupid. And you start to question your life and what you’re about.”

What happens in encampments is often invisible in the official data, including both reversals and fatal overdoses. The county does not track how many overdose deaths are happening on the street, or even overall deaths of unhoused people. I asked Seth Gomez why that is.

“It’s not that it hasn’t been tracked before. It’s just that the data requirements made it difficult to know for sure if somebody was homeless,” says Gomez.

In short, the county and coroner’s office don’t record whether someone is housed when they collect overdose data or data about deaths. So we don’t have that data for unhoused people.

And there are other reasons why we don’t have an accurate overdose count in unhoused communities.

People are often reluctant to report overdoses. If you’re unhoused, you have reason to be mistrustful of official emergency responders like police or paramedics. Drug use and possession is illegal. Unhoused people are already a target of police harassment, they often show up to enforce evictions. And police can come when 911 gets called, making people less likely to dial.

Even though the county isn’t tracking the number of overdoses in people experiencing homelessness, evidence suggests that more people are overdosing, more people are dying, more people are reversing overdoses. But those increases aren’t showing up in the official counts. In fact, the county data shows that emergency calls for overdose have actually been relatively steady since 2019. But we know that deaths have increased.

Alameda County doesn’t have the full picture of how many overdoses are being reversed by naloxone either.

The county provided KPFA with data about 911 calls for overdoses – it’s about 4 per day. But even THAT’S not the full picture, because people don’t always call 911 if they’re able to successfully revive someone with Narcan.

Advocates say the unhoused community has become so intimately acquainted with reviving others themselves, they might not bother calling.

I spoke with an Oakland resident named Jeremiah, who has reversed at least four overdoses. One night in early July, he was riding the BART train home to West Oakland. It was the last train of the night and he was on the last car, since he had his bicycle. A group of people boarded the train at MacArthur Station in Oakland and sat in the back car to smoke.

Jeremiah isn’t sure what they were smoking – but a woman in the group immediately lost consciousness after taking one hit. He knew he had to react quickly. Jeremiah carries Narcan wherever he goes. He went over to the woman, sprayed a dose of Narcan up her nose, began jostling her and calling to her to wake her up, and then administered a second dose.

This isn’t an isolated incident. BART started keeping data about overdose reversals in mid-2019. Public records say BART police have administered Narcan 79 times since then. So far in 2021, at least 3 dozen people have been revived on station platforms and trains.

But overdose reversals like what Jeremiah did won’t show up in any public numbers. Paramedics weren’t called, police weren’t deployed. And that’s because the people reversing the most overdoses on the streets and keeping each other alive are other unhoused people.

They do this with support from local mutual aid groups and outreach workers.

Putting life-saving supplies into the hands of community

It’s about 10:30 in the morning on a Tuesday in August of 2021. The grassroots mutual aid group West Oakland Punks with Lunch is going down Martin Luther King Jr. Way, under the 980 freeway overpass in Oakland. Four of the “Punks” are pulling utility carts along the street.

The carts are piled high with hygiene supplies, syringes, masks, clean glass pipes for smoking crack or meth – and boxes of the overdose reversal drug Narcan. Every so often a pack of syringes falls off the cart, and I bend over to pick it up.

Volunteers offer items to passers-by: toothbrushes, toothpaste, condoms, Narcan, fire extinguishers, and burritos.

Punks With Lunch is one of four organizations in Alameda County who bring sterile supplies directly to unhoused people who use drugs. In just two hours, they see 78 people.

It’s noisy and precarious so close to the freeway. Residents come out of their tents, cars and temporary shelters, some still wiping sleep from their eyes. Ale Del Pinal, who founded Punks With Lunch in 2015, greets many of them by name.

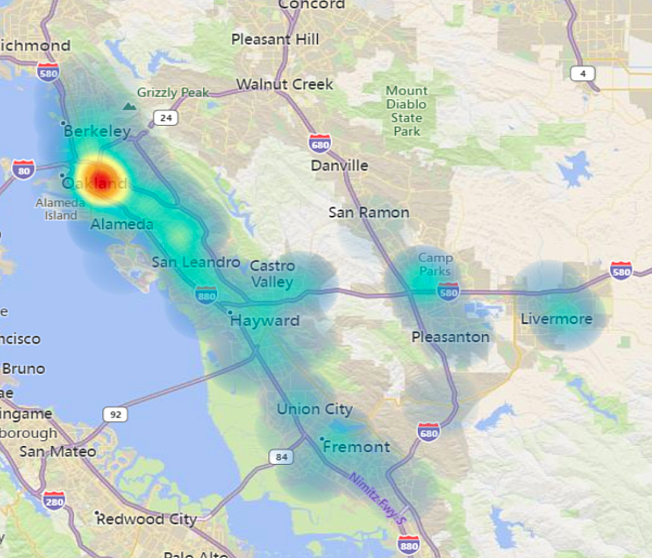

Ale’s tone is light, but the reason they’re here is serious. The county keeps a color-coded heat map of opioid overdose hotspots. And this spot, in West Oakland, is in the bright red epicenter.

Opioid overdose “heat map” supplied to KPFA and Street Spirit by Alameda County illustrates ZIP codes where emergency services are most often called for opioid overdoses.

The scale of the emergency can feel overwhelming.

Just the day before, one of the Punks With Lunch participants living here was murdered. There are prayer candles outside the tent where they used to live. There’s a woman walking down the street waiting for medical care because she was bitten by her dog. While we’re there, a man parks a large white van next to the tents and starts yelling through a megaphone at the unhoused residents to repent and turn to Jesus. It’s chaotic and loud and stressful to live here. This is the experience of homelessness, even before the pandemic.

One resident named Indiana, tells me, “This has been going on before. This is the pandemic, okay? This is it. Prepare yourself for doom.”

Punks with Lunch never halted their outreach here during the Covid pandemic. Katie O’Bryant does outreach for the group.

“I’ve been working like in homeless services since I was a homeless kid actually. When I was 17 was one of my first jobs was working with other homeless youth,” Katie says.

Katie was homeless for over 10 years. She also describes herself as a long time drug user. And like many people who do this work, overdose has touched her life. Katie tells me, “I’ve lost a lot of people to overdose, and I’ve continued to lose people.”

Punks with Lunch does not collect personal information about the people who take supplies. But they do count overdose reversals. Since 2019, in West Oakland alone, they’ve counted almost 1100 overdose reversals.

“As a really small organization, we saw 670 overdose reversals this last year compared to the 400 and something from last the year before,” says Ale Del Pinal. “So it’s been pretty drastic.”

And that’s why harm reduction groups like Punks With Lunch are giving out thousands of doses of Narcan and training people how to use it.

If someone wants to get treatment to reduce opioid use, like with methadone or suboxone, Punks With Lunch will make sure they can see a medical provider. But it’s not an expectation or a requirement. One of their participants, LG, tells KPFA, “I think they’re doing great work. They go out of their way to help people. They have the attitude of a proletariat worker. And they take you palms up, how you are.”

This approach is called harm reduction. It’s a philosophy that basically says public health should meet people where they’re at, including if they use drugs. If someone’s going to use drugs, they should be supported with sterile supplies, information, and food to minimize risk as much as possible.

An outreach worker with Punks With Lunch pulls a handcart with sterile supplies in West Oakland / Ariel Boone

On top of the harm reduction work, Punks with Lunch also started helping people manage the risks of getting Covid while living on the streets because the pandemic is hitting them disproportionately hard.

The added stress of living under the threat of the virus is impacting mental health and driving up substance use, too. Some unhoused people are out of work from Covid. Many can’t afford food and still haven’t gotten their stimulus checks because they need help filing the paperwork.

Unhoused people in the county also continue to face ongoing evictions from the public areas where they stay, known as sweeps. And then, there’s the isolation.

When Bay Area public health departments issued shelter-in-place orders in March 2020, Thad remembers feeling scared. “They told us to stay within our isolated group as much as possible and not to interact with other camps,” he says, “which is somewhat impossible when you’re trying to have money and as a drug addict. So, it just seemed kinda like pretty daunting, felt kind of alone. Or like we’re just going to be left behind.”

“This is a really culturally collectively traumatizing experience,” says Savannah O’Neill, Associate Director of Capacity Building with the National Harm Reduction Coalition. “And what we know about trauma and drug use is that they’re really linked together, and that traumatic events, isolation, loss — economic/job loss, as well as loss relating to death — all can trigger drug use, even deeper drug use for people or people who’ve had long periods of sobriety.”

A CDC report from last August says 13% of U.S. adults started or increased their substance use during the pandemic to cope with stress.

And the same is true for people living on the street. In the early days of the pandemic, Ale said the demand for clean syringes and Narcan went way up.

“I think we ended up giving out over 16,000 syringes in one week, almost double what we were doing before. It really fluctuates,” Ale told me by phone in April 2020, just after the first lockdown.

“We’re giving lots and lots of Narcan out. For a while, we were seeing a huge uptick in overdose reversals reported. I think we saw over 20 in one week.”

Sterile syringes are really important for people who inject drugs like heroin. Punks with Lunch started giving out more Narcan too and hearing about more overdose reversals.

“Every time we give out Narcan we’re like, ‘Have you had to reverse an overdose in the last week?’ And we get three yeses,” says Katie O’Bryant.

Ale continues, “It’s important that we record every reversal that we possibly can, so that we can show that the people who are most impacted by the War on Drugs are also the people who are fighting it on the ground. Literally it’s life and death. And it takes the community to take care of themselves.”

The people reversing overdoses on the street

Ale de Pinal regularly hears stories where unhoused people are reviving each other. But because no one is collecting this data, unhoused people don’t get credit for the lifesaving work they do.

I’m talking with Thad, who carries Narcan wherever he goes.

“I should have some on me right now. If I don’t…” he trails off.

He pulls out a red zipper pouch from under his shirt, it hangs around his neck.

“Yeah, I do. Yeah.”

Thad carries the nasal spray version. “Try and get at least one, if not more,” he explains, “because you have to give them one, then wait three minutes. Then give them another one. So a lot of the time it’s going to take more than one, and you’ve got to start breathing for them. After five minutes, seven minutes, you start getting brain damage.”

Thad’s first overdose was last year. Since then, he’s used Narcan to reverse 10 overdoses for other people.

“Before that, I hadn’t administered Narcan, but I’d had to breathe for someone for a long time and give them mouth-to-mouth. And so since then I’ve had to Narcan and been there when people have Narcanned a bunch of times. And luckily, thank god, I’ve not lost anybody myself — because I’m just determined to breathe for them, if I have to breathe forever.”

The unhoused community gets a barrage of signals that their struggles don’t matter. The county doesn’t record how many people lose their lives on the street. Sweeps and evictions continued last year during the pandemic, even in the middle of major storms and bad weather. And besides hotels, there was no drastic action to house everybody who needed it during the Covid pandemic.

But their struggles do matter. And people within this community prove this every time someone reverses an overdose, which is at least half a dozen times a day. It’s a way of saying, your life is worth saving.

I’m just determined to breathe for them, if I have to breathe forever. – Thad, Oakland resident

Nationwide, synthetic opioids like fentanyl accounted for 83% of drug fatalities last year.

The pandemic is partially to blame. Advocates say it’s made the drug supply much less reliable.

Fentanyl is also being mixed into street drugs, and people may not even know they’re consuming it until it’s too late.

“We’ve had to identify all risk factors for experiencing an opioid overdose. And those risk factors now include somebody who is using any drug that is acquired from the street,” says Seth Gomez of Alameda County Healthcare for the Homeless.

That includes drugs like cocaine or methamphetamine, and pills sold on the street that look like real medication.

“These pills are marketed essentially to be the real prescription product, like Xanax bars. But because these drugs are made on the black market on the streets and they’re counterfeit, they can easily disguise these other types of drugs inside of them.”

Katie wants a system where people can test their drugs for safety. Plus, fentanyl analogs, like carfentanil, are so much more potent that it can take a lot more Narcan to revive someone.

“The biggest indicator to me is how much Narcan I give out,” says Katie, “which is boxes and boxes and boxes a week. And also like hearing that people need sometimes six doses to revive people. So it’s not just making sure people have Narcan, but they have enough.”

The Punks With Lunch team has given out over 8,000 doses of Narcan.

Taking a broader look, the reason that people consume drugs in secret in the first place — and the reason people don’t have a safer supply — can be traced back to the drug policies of the 1980s.

President Reagan massively expanded the War on Drugs, pushing draconian and punitive laws through Congress that resulted in mass incarceration of mostly Black people in the United States. Today, federal arrest data so far shows people being convicted for fentanyl charges are also disproportionately Black.

Nearly three decades of research has shown that harm reduction and syringe access programs like Punks With Lunch, are effective at preventing fatal overdoses and stopping the transmission of diseases, like Hepatitis C and HIV/AIDS.

But outside of California, these programs are still completely illegal in 11 states, where Reagan-era laws prohibit providing free sterile syringes. The United States has been having this debate since the late 1980s. Even though harm reduction is proven to save lives, it is practiced by only a relatively small subset of people, and there’s a prevailing belief in the mainstream that finds it controversial to provide these life-saving supplies to people dealing with addiction.

Meanwhile, people continue to die of overdoses on the streets.

It is a preventable crisis, say advocates. Overdose doesn’t necessarily need to follow drug use. And with Narcan, death doesn’t need to follow overdose. Katie O’Bryant from Punks With Lunch says there are things we can do right now to stop the deaths.

“I would love to see an end to the drug war,” Katie says. “I would love to see safe consumption sites for people. I would love to see Narcan available everywhere, would love to see more sharps containers everywhere, in public restrooms. If drugs were legalized, if I’m dreaming – if I’m dreaming big, right? — and people could have like absolutely safe supply, it would save so many lives, and it would also improve the quality of people’s lives so, so much, so drastically.

“That would be a beautiful thing.”

Grief and loss

The grief and loss during this crisis has been profound – and especially so for unhoused people using drugs and their communities.

In June this year, two men were found dead from suspected overdose at Civic Center Park, in Downtown Berkeley, just two blocks from the KPFA station. A week later, I went there to meet Ana, a mom from Mexico, who’s been unhoused and living around the park for years.

“People can get lost alcohol, drugs, anything on everything, because this is not a human way of living,” Ana tells me. “We need to be intoxicated in order to endure what we endure.”

The morning of the overdose, Ana spent time with Eric Cumby. The two of them were chatting in the park, and he left to run an errand. A couple hours later, she saw police turning his body over. Then Ana heard a voice call out in the park that another body was found.

Photo of Barry Biddulph / Facebook

Barry Biddulph was a friend of Ana’s. He was part of the fabric of the park. On Facebook, there’s a photo of Barry smiling and holding his fist against a Charlie Brown statue, like he’s going to give the statue a knuckle sandwich. A few hours after residents watched police remove their bodies, Ana had to go to her job at a department store.

“I was riding my bike to work that afternoon and I was shaking,” says Ana. “You don’t see people die like that in the street, like, like dropping dead … It’s traumatizing, and we had no help. Nobody addressing us, nobody talking to us, not one human being.”

Ana says residents heard there was a bad batch of drugs around. But she doesn’t know for sure. Toxicology reports take months. And it’s not certain anyone from the county or city will come back to the park to tell residents the results and give them closure. But Berkeley NEED, another local harm reduction organization, came out to the park in the days after the overdoses, and handed out Narcan and fentanyl test strips. Ana carries them in her purse now.

“See, we within the homeless community, we do look after each other. That’s how I’m still standing,” she says. “We share with each other when I don’t have smokes, somebody does. When I got money, I share. It’s that kind of beautiful relationship that is humanity. And we do it out of necessity because we don’t have it from the government of this country.”

Advocates say the U.S., state and local governments did not do enough to stop this wave of overdose deaths — that the government left them behind to deal with an overdose crisis themselves, on the street, by not taking sweeping action to house everybody, or offering safe locations for people to use and test their drugs, by not ending encampment sweeps and evictions, by criminalizing people like Thad. Ultimately, they say, it fell to unhoused people dealing with addiction to support each other. And save their own lives.

The people in this story are surviving, for now. When I last saw Thad, he was intent on finding showers and a place to live. He said he might try a medication called suboxone, which is used to treat opioid addiction.

This story was produced and reported by KPFA producer and reporter Ariel Boone, and edited by Lucy Kang from the KPFA Storytelling Project and Kavitha Cardoza. Wren Farrell provided voice coaching. This report is a project for the 2021 California Fellowship of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, in collaboration with KPFA and Street Spirit. Many thanks to West Oakland Punks With Lunch, the HIV Education and Prevention Project of Alameda County, LifeLong Medical’s Street Outreach teams, the Harm Reduction Coalition, Seth Gomez, and everyone who spoke with me for this story.

Listeners can contact Alameda County Healthcare for the Homeless and sign up for a training on becoming an opioid overdose responder in your neighborhood. They offer them every Tuesday online at 1PM – and they provide free Narcan.

[This article was originally published by KPFA.]