Investigation Uncovers Abuse of Nonverbal Woman in 'Enhanced' California Group Home

This story was originally published in KALW with support from our 2022 Journalism Fellowship.

Katrina Turner, a nonverbal autistic woman, walks with her father Pat Turner outside of the group home in which she lives

Chris Egusa

“When I walked in, Katrina had a black eye and I was like, oh my God. And my coworker said, "Kylie, it's not even like the worst part.”

It’s early fall 2022. I arrive at a broad, dark brown house in a suburb outside of Sacramento, California. A huge tree shades the home from the last remnants of the summer heat.

I’m here to meet a couple who contacted me about a story a few months earlier – Pat Turner and Elaine Sheffer. We’d been speaking over Zoom since then. We exchange greetings and Elaine gives me a brief tour of the house. It’s immaculate. Even the houseplants look tidy.

Elaine Sheffer and Patrick Turner stand together in front of their home near Sacramento, CA.

Chris Egusa

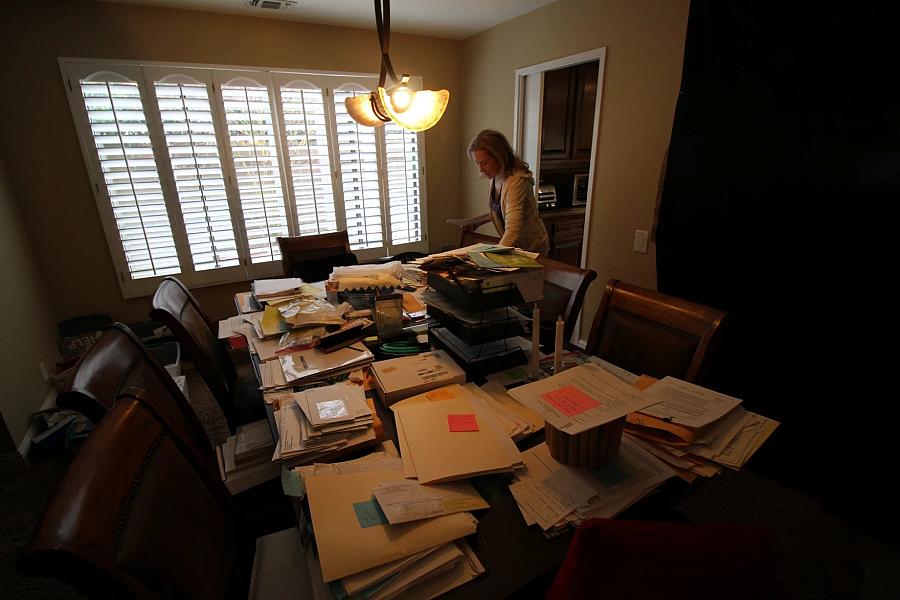

As we circle back toward the entrance, we make our way to a room that’s been sectioned off with heavy black curtains. As we push through the fabric and enter a dining room, I feel like I’m stepping into another world.

“I've got thousands of documents,” Elaine says. “This is the war room.”

It looks like a prosecutor’s office the night before a trial, with reams of papers piled high on the table, and stacks of crates stuffed with documents.

Elaine Sheffer looks over documents she's collected during her investigation of mistreatment of her stepdaughter, Katrina.

Chris Egusa

I ask Elaine to describe the scene for the recorder. She thinks for a moment, and then responds, “nightmare.”

The name “Katrina” is printed on many of the documents scattered around the room. Katrina, 43, is Pat’s adult daughter, and Elaine’s stepdaughter. She’s been diagnosed with autism, epilepsy, along other conditions, and is currently living in a group home for adults with developmental disabilities. She’s also nonverbal — she doesn’t speak at all, though she does make sounds. The couple says that Katrina is stuck in a system that has allowed her to be abused and neglected over and over again. They’ve been gathering all this paperwork to try and hold that system accountable.

I follow Elaine into the kitchen area with a fold out table that’s covered with more papers — the “Mini War-Room.”

I ask her how much time she thinks she spends going over this paperwork. “Anywhere between 10 and 14 hours a day,” she says. “Sixty, seventy hours a week.”

All these hours, and all of these documents — Pat and Elaine say this is what it takes to advocate for someone who can’t speak for themselves. They’ve reached out to every agency and every group they can think of. Even the Sheriff’s office and their local representative.

According to them, it’s always the same: concerned voices and supportive words, but ultimately… nothing. They say it’s like living in a different reality.

“Twilight Zone,” Elaine says. Pat adds, “Because they're asking you or they're talking about it, but they don't do anything.”

A Promise of Safety

Elaine is in her early 60s. She’s high energy, enthusiastic, with a penchant for cheetah print. Pat is in his mid 70s.

The two are engaged. They started dating in 2016, after each going through a divorce. And as they got closer, Elaine began taking on a bigger role in looking after Katrina. “It just seemed natural to me,” she says. “That's what you do. It goes with the territory.”

Elaine’s motivation for getting so involved is also deeply personal. “My brother passed away,” she tells me. “By suicide, I think it was in 2014. He had had a head injury when he was 18. You know, he was disabled permanently.”

She’d seen how difficult it had been for him to navigate the system. To get the help he needed. “I think a big part of the reason that he committed suicide right before he turned 50 was just, he was just over it,” Elaine says.

Pat says that, since she was a little girl, Katrina has been a handful. “She was destructive, into everything and would just tear up your house.”

Katrina has this really sweet side, but the reality is she can be extremely difficult to work with. Pat tells me meltdowns and tantrums were par for the course. She can physically hurt other people or herself. Sometimes she smears her feces. As a kid she needed 1 on 1 supervision all the time, sometimes 2 on 1. That’s actually still the case. It was more than Pat and his ex-wife could provide at the time, so Katrina went to live at a group home.

But, the system is really tough for people like Katrina. She bounced from one home to another over the years. At one point she spent over 6 months in a hospital room because the state wasn’t able to find a suitable placement for her.

Pat and Elaine were determined to get her somewhere safe.

In early 2021, a solution seemed to emerge. The couple was told that a spot had opened up nearby in this new kind of home. An Enhanced Behavioral Support Home, Or EBSH. These homes were designed specifically for people with the most challenging behaviors and intense needs, like Katrina.

"We were hopeful because an EBSH home is overseen by the state,” Elaine says. “So we were hopeful that this would mean that there'd be a little bit more, you know, hands on and that there wouldn't be such an opportunity for neglect or abuse.”

“So we were hopeful that this would mean that there'd be a little bit more, you know, hands on and that there wouldn't be such an opportunity for neglect or abuse.”

EBSHs have only been around for about 6 years. They’re part of a plan to transition away from big state-run institutions and toward smaller community-based homes. These homes house a maximum of four people at a time. They’re only a fraction of the over 6,000 total group homes for California residents with developmental disabilities. As of April 2023, there were about 65 licensed EBSHs scattered throughout the state, with more in development.

On paper, it sounded perfect to Katrina’s parents. EBSHs are supposed to have plenty of resources, highly trained staff, and extra scrutiny from regulators.

“She moves to the home and we thought everything was gonna be okay,” Elaine says. “But it's not. It's horrible.”

The Conditions for Abuse

There’s mounting concern among advocates that these high-intensity group homes like EBSHs, and another similar type of home called Community Crisis Homes, are becoming breeding grounds for abuse, neglect, forced restraint, and other forms of mistreatment.

Judy Mark is the Co-Founder and President of Disability Voices United, a California-based advocacy nonprofit.

“It is those people who are non speaking or minimally speaking, who are at the highest risk in these congregate settings,” she says. “And are often pushed to the side and ignored.”

“It is those people who are non speaking or minimally speaking, who are at the highest risk in these congregate settings.”

Judy has an adult son with autism, and has spoken with hundreds of disabled people and their families. “In these enhanced behavioral homes, people are put there because they have ‘behaviors.’ But for me, behavior is communication.”

She says that front-line staff are usually minimum wage or close to it, and they’re often not equipped to work with people who have very complex needs.

“The other thing that we see a lot in these kinds of care homes is that the employees do not feel accountable to the people they serve. They feel accountable to their employer, and therefore they cover up for each other. And we see that on a regular basis where, ‘I did see that abuse happening, but I didn't want to report on it because I was afraid I would lose my job.’”

A Complicated System

California’s developmental disability system was set up over 50 years ago, and it’s become very complex. The easiest way to understand it is to imagine a pyramid. At the bottom of this pyramid are the 400,000 Californians with intellectual and developmental disabilities who receive some kind of service from the state. In the middle of the pyramid are 21 nonprofit agencies called Regional Centers, which coordinate and oversee all of these services. Sacramento’s is called Alta Regional Center. At the top of the pyramid is the Department of Developmental Services, or DDS. This state agency manages the budget and oversees the entire system.

The final player in this system is over to the side of the pyramid. It’s called Community Care Licensing, or just Licensing. It's a division of another state agency called the Department of Social Services. Licensing is responsible for the actual facilities — the buildings and homes that house residents — and for enforcing regulations.

All of these agencies declined my requests for interviews. Instead, they sent me written statements in which they responded to claims and answered questions.

As I began reporting this story, one of the first things I did was request data on abuse and other incidents from the Department of Developmental Services – that’s the big statewide agency that handles all the funding. The department recorded a total of 165 incidents of suspected abuse and exploitation over the past 6 years. It’s important to note that these are only suspected incidents, not proven. But still, that’s an average rate of suspected abuse per year of 20%, or one in five residents.

That’s an average rate of suspected abuse per year of 20%, or one in five residents.

In a written response, DDS said they’re constantly working to lower incidents of suspected abuse through better reporting, education, and outreach.

But what makes these numbers even more concerning is that they may actually be underreported. That’s because, again, many people who live in EBSHs have profound disabilities, and are either nonverbal or have significant communication challenges.

“When they're abused, the police do not consider them good witnesses,” says Judy Mark. “Or they consider them unreliable witnesses. And then there is also this really sort of ableist notion that a person with a profound disability, they don't really matter. They're not real human beings. And therefore, if they are abused, it's okay.”

Many EBSH residents can’t advocate for themselves. That’s why cases of mistreatment often come to light only when another party takes notice — a concerned employee, a neighbor, or a family member.

Behind Closed Doors

Katrina Turner moved into an EBSH called The Illinois Home in March 2021. Pat Turner tells me they were not aware that the facility was under investigation at the time.

Through another public records request, I was able to obtain hundreds of pages of reports and communications about the Illinois Home from Community Care Licensing. These documents show that just a few months before Katrina moved in, the agency had received a lengthy email from an employee, who alleged medication errors, neglect, and fraud by management.

And, in the months following Katrina’s move-in, Pat and Elaine tell me that a number of red flags began popping up.

They say they noticed that one of Katrina’s controlled medications seemed to be constantly disappearing. They heard rumors of staff drinking and having sex on the premises. Documents show staff at the home also reported this behavior to licensing.

Pat and Elaine say they often found mysterious bruises on Katrina.

I reached out to Sevita Health, the company that operated the Illinois Home starting in July 2021. I gave them a list of all the claims in this story. In a one-page statement, the company declined to comment on any specific claims, citing privacy concerns. In the statement, Sevita writes, “our top priority is the safety and wellbeing of the people we serve… Sevita promotes ethical practices at all levels of the organization.”

Pat and Elaine have described dozens of concerns to me. I’m just going to focus on a couple.

The first incident was in February, 2022. Elaine received a surprising text, then an email right after. They weren’t formal communications from an administrator, but messages from a staff member’s private accounts.

Elaine forwarded me the email from staff member Kylie LeBlanc. It described a series of abusive incidents. The attached photos showed Katrina looking mournfully at the camera, with a deep raised purple blotch spreading below her eye. Other photos show dozens of massive holes in the walls. I remember feeling sick when I first saw them.

A large hole in the wall of Katrina's room.

Chris Egusa

I reached out to Kylie LeBlanc, and she agreed to talk with me.

“When I walked in, Katrina had a black eye and I was like, oh my God. And my coworker said, 'Kylie, it's not even like the worst part.'”

“When I walked in, Katrina had a black eye and I was like, oh my God. And my coworker said, 'Kylie, it's not even like the worst part.'”

This coworker took her to see Katrina’s room, where, along the wall, there was a row of holes. Kylie believes they were caused by Katrina banging her head against the wall. According to her, the row of holes was right around 5 feet, Katrina’s height.

Kylie Leblanc was a staff member and whistleblower at The Illinois Home, an Enhanced Behavioral Support Home near Sacramento, CA

Chris Egusa

“I said, how did she get this black eye? And he goes, 'I don't know. But I know people are locking her in the room. They are putting her in her room. They're closing the door and holding it shut while sitting in a chair.'”

Kylie’s unnamed coworker decided not to speak to me on the record. And when Licensing investigated this incident, the accused employees denied the claims.

Katrina is supposed to be monitored 24/7 because she has a history of self-injury. Kylie explains that being left alone is severely triggering for her. So, if she was shut in a room by herself, the whole experience would have been confusing and frightening for Katrina, and she may have resorted to self injury.

“And that is the moment where I called Elaine,” says Kylie. “And I said, ‘Hey, um, I don't know how else to say this. I walked in today and Katrina has a black eye.’”

Elaine recalls the incident. “I got the text from Kylie on Monday evening. I went over there Tuesday, and full black eye. We had never been notified of anything.”

A photo showing Katrina Turner with a black eye, sent to regulators by staff member Kylie Leblanc.

Chris Egusa

Elaine strongly believes that had Kylie not reached out, Sevita was going to keep the incident from her and Pat.

Both Elaine and Kylie believe that management hid Katrina’s black eye because there was more to the story than just a surface mark. They believed she’d suffered a concussion.

“She was also at that point having issues with throwing up and losing control of her bowels,” explains Kylie. “Which is another sign of some kind of head injury or a concussion."

This sent Elaine into high alert. After receiving the message from Kylie, Elaine says she drove to the Illinois Home and demanded that Katrina be taken to the ER.

But, even though the staff took Katrina to a clinic, she never received a head scan or treatment for a concussion. According to Elaine, the staff didn’t advocate for it.

Even though the staff took Katrina to a clinic, she never received a head scan or treatment for a concussion.

Abuse and Inaction

Kylie says that she submitted complaints to the HR department of Sevita Health, the company that operated the home, but the incidents kept happening.

“Which is also scary to think about. That didn't scare the company enough to be like, ‘Wait, let's fix this.’”

So, she decided to go straight to the regulators. She sent photos and a full writeup of the concussion incident, along with a slew of other complaints, to Alta Regional Center and Community Care Licensing. Both of these entities are supposed to work together to investigate any complaints.

At first, Kylie says she was hopeful. “They actually had a meeting with three employees from Alta Regional and from licensing, and we sat at Alta Regional. We had about an hour-long meeting of everything that was going on.”

Documents from Licensing show that Kylie also submitted allegations that staff mismanaged residents’ medications and denied residents their personal rights. Disturbingly, I found multiple allegations from staff that other staff members were holding clients’ faces near feces as a form of punishment.

“That conversation, I mean, it seemed promising in the moment,” says Kylie. “I was excited that they all seemed interested, and they cared, and they said they were gonna do things to fix it. And absolutely nothing happened.”

She describes being incredibly frustrated.

“Licensing came out, they did an audit, and then they left. Alta Regional came out, they did an audit, and then they left. And then the answer was like, ‘We're still investigating, we're still investigating, we're still investigating.’ I know investigations take time. But while they were still investigating, it was all still actively happening.”

"I know investigations take time. But while they were still investigating, it was all still actively happening.”

Alta Regional Center says it did take action. In response to my questions, Alta wrote that between March 2022 and June 2023 the Illinois Home was “required to develop a corrective action plan and the Regional Center stopped referring new individuals for placement there.” So, even though Katrina and the other residents remained, Alta prevented any new residents from moving in.

Kylie says that one result she did see was related to her own job. She and another employee I spoke with believe that they were targeted and pushed out by Sevita Health for speaking up against the abuse. Eventually, Kylie was terminated.

Again, Sevita Health did not respond to specific claims.

The consequences that Kylie, Elaine, and Pat were expecting didn’t materialize. Even though the home wasn’t allowed to take in new residents, it continued to operate.

Meanwhile, Pat and Elaine say they were still being kept in the dark by management of Katrina’s Home. And, with Kylie out, they’d lost their main source of information.

A New Administrator and New Incidents

In March, 2022, a new administrator came into the home — a woman named Ileya Silva. She had a strong reputation for running things by the book.

To Pat and Elaine, Ileya seemed different than the previous home administrator. It felt to them like she was trying to be transparent.

Then, in June 2022, Ileya sent them a bombshell report.

“Katrina had been taken out in the home van,” explains Elaine. “And when she would take her seatbelt off and stand up, or attempt to, the staff member driving would slam on the brakes and, like, brake check her. So that explains a lot of the bruises that she had on her lower back and the front of her legs.”

“In this van,” says Pat. “This is kind of like a little mini motor home with nothing in it. So, when you get up, you have a lot of open space. She would've gone flying all over that place.”

Several documents I obtained from Licensing describe the agency’s investigation into the incidents. In a report dated June 16, 2022, one staffer is quoted as saying the driver of the van “Will brake check 2-3 times. Then she was laughing like it’s a joke. Happens all the time. I have worked here for 3 weeks. Have gone out 5 times. Happened 3 out of 5 times.”

The driver of the van “will brake check 2-3 times. Then she was laughing like it’s a joke. Happens all the time."

Other reports from the investigation indicate that three different staff members were doing this over a period of several months.

I ask Elaine and Pat how the incident made them feel. “Disgusted,” replies Elaine. “We feel it's criminal.”

Ileya told Pat and Elaine that the company was suspending the three employees accused of brake checking Katrina and the other residents. Shortly after that, one of the employees quit, and the other two were terminated.

It was a good start. But amidst the countless other incidents, it still felt like a small victory to Pat and Elaine. What about the company itself — Sevita Health? Or the management that allowed that culture to persist?

According to statements from Licensing and Alta, the agencies increased pressure on Sevita to improve conditions. But, the company would continue operating the home for another year.

I wanted to better understand what the consequences are for a facility that has received as many citations as the Illinois home. What are the actual financial penalties the company receives?

DDS told me that sanctioning — the way Alta Regional Center had prevented new residents from being placed at the home — is one form of discipline that can affect a company’s bottom line. Community Care Licensing does have the power to assess civil penalties, but the amounts I’d seen seemed surprisingly low to me. The Illinois Home was fined a total of just over $1,500, in contrast with the home’s total yearly revenue of over $1.5 million, according to DDS.

The Illinois Home was fined a total of just over $1500, in contrast with the home’s total yearly revenue of over $1.5M, according to DDS.

In response to my questions, Community Care Licensing said, “The Department licenses facilities in accordance with state law.”

Katrina

A few months after my first meeting with Pat and Elaine, I head back to Sacramento. It’s December 2022. This time, Elaine and Pat have agreed to let me tag along on a visit to Katrina. I arrive at a large, ranch-style house. With its beige, stucco walls, the house completely blends in with the rest of the neighborhood.

We walk in the house, and Katrina’s nearby to greet us. Right away, I get it. She’s nonverbal, and yet she absolutely communicates. Her large, expressive eyes bounce between us as she searches and probes our faces. She makes soft moaning sounds as her parents embrace her.

The staff give the family space. We all gather in a large entry area, where I’ve agreed to take some photos for a family Christmas card. Elaine and Pat cajole her into standing relatively still with them as they pose together.

Patrick Turner and Elaine Sheffer pose with their daughter, Katrina for a Christmas card.

Chris Egusa

Elaine and Pat have brought Katrina some big fuzzy Christmas socks. My gift to her is a bag of her favorite snacks — gummy bears and lemonade. Her eyes light up when she sees the contents of the bag.

“The lemonade’s a hit,” remarks Elaine.

The sense of tension looms heavy in the air. In between hugs, Pat and Elaine scan the home, evaluating everything.

Suddenly, Katrina leaves her parents, walks up to me, and takes my hand. She makes eye contact for a moment, and then leads me around the house for a bit. I get the feeling that she’s showing me some of the places that make up her world. The dining room, the kitchen, and the living room where she likes to watch Barney and Michael Jackson music videos.

Later, I snap photos as Katrina walks with Pat around the front yard. Her skin shows fading bruises and scars. And, though she’s barely middle-aged, she walks with the stooped shuffle of someone much older. She gazes at him adoringly as they shuffle along, and he puts his arm around her.

As we prepare to leave, I think about how, much like the home in which she lives, Katrina’s existence goes mostly unnoticed by the larger society around her. Unremarked upon. There are locks and gates to keep her from leaving on her own. Neighbors in town might see her and the other residents on a van ride with staff. But, they don’t know the reality of her life behind closed doors.

Neighbors in town might see her and the other residents on a van ride with staff. But, they don’t know the reality of her life behind closed doors.

A New Chapter

In the Summer of this year, something did finally change.

As of June 30th, 2023, Sevita is no longer operating the Illinois Home. DDS confirmed that Sevita was not able to meet care standards and voluntarily gave up operation of the home. A new small company would be taking over.

The transfer went through nearly a year and a half after Katrina suffered the black eye and concussion.

Pat and Elaine tell me they’ve met with the new home operators, and their impressions are positive so far. But, due to the trauma of the past year and a half, they remain unconvinced that the system will protect Katrina if things go south again.