A coastal road connects these patients to dialysis. Climate change could make that harder

This story was produced with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 Impact Fund for Reporting on Health Equity and Health Systems.

Other stories by her include:

Pacific Islanders Have a Harder Time Getting Kidney Transplants Than Other Patients

Native Hawaiians Face High Rates of Diabetes. That Means More Need for Dialysis

State Rules Make It Harder To Open Dialysis Centers In Hawaii

Why In-Home Dialysis Is Becoming A More Popular Option In Hawaii

State Greenlights New Dialysis Center In Kahului

The Pandemic Vastly Expanded Health Care Access In This US Territory. That May End Soon

Many Pacific Islander Patients Have To Move To Get Life-Saving Access To Dialysis

HONOLULU CIVIL BEAT

To read this story in Hawaiian, click here.

Elizabeth Kaleo was standing on the side of the road near her house in Hauula when her phone started to chime, the musical ringtone punctuating the quiet Oahu morning. She pressed a green button and an automated voice spoke.

“This is the Handi-Van,” the recording said, notifying her that her ride would be arriving promptly in 10 minutes. “Please be waiting at your pickup location.”

Kaleo pressed 1 to confirm she was ready. It was nearly 8 a.m. and she had been standing outside patiently for about half an hour, expecting Honolulu’s paratransit services to pick her up on the hour and take her to her dialysis appointment 21 miles away.

The 63-year-old has only been going to dialysis since the day before Christmas, but already it’s become a familiar routine.

Three times a week, she wakes up at 5 a.m. to make breakfast and get ready for the four-hour blood filtering treatment. Her appointment is usually at 10 a.m., but she tries to get there early in case there’s an empty seat so she can start sooner.

Kaleo sits in the back of the van during the hourlong drive south along the two-lane Kamehameha Highway. The bus snakes along the Windward Coast, gray clouds hovering threateningly overhead as Kaleo checks her phone and watches the coastal landscape go by. The van’s steady pace is punctuated by stops for other passengers, including other dialysis regulars.

But while her commute is doable now, that may not always be the case.

Eʻe ʻo Elizabeth Kaleo i ka Handi-Van ma hope o ka hoʻopau ʻia ʻana o ka hoʻomaʻemaʻe koko ʻia.

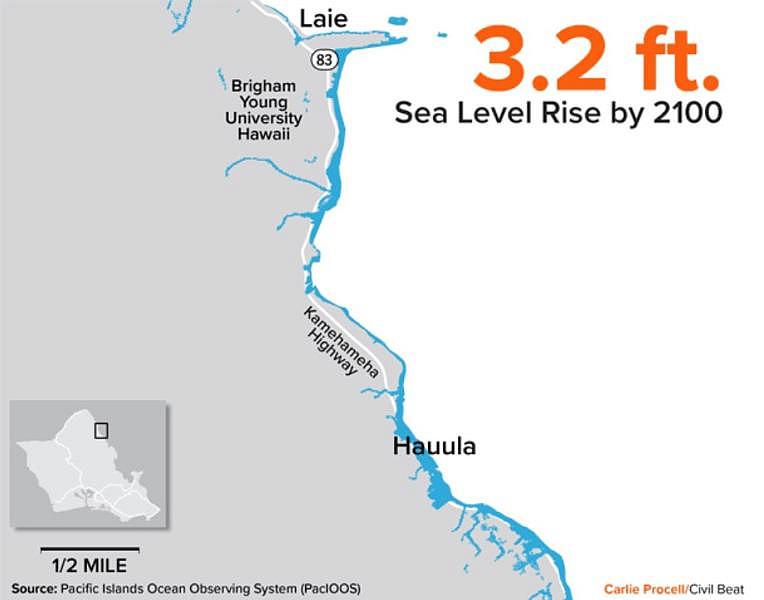

A gradually rising water table is already eating away at the highway as sea level rises due to climate change, says Chip Fletcher, the interim dean of the School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology at the University of Hawaii Manoa. Storm surges with king tides occasionally overflow parts of the coastal road, forcing temporary road closures.

Fletcher and other scientists who have analyzed the highway predicted that portions could be inundated as soon as 2050, raising questions about how residents will access essential services like dialysis. While Kahuku Medical Center is considering adding a dialysis center, the high cost and regulatory barriers mean it would be years away, even if it gets off the ground.

State Rep. Sean Quinlan, who represents a stretch of North Shore communities including Hauula, hopes a solution is near.

“This is a huge issue and it’s really exacerbated by how often that road gets closed. That road gets closed so often in inclement weather,” he said.

‘Existential Transportation Issue’

In 2019, the Hawaii Department of Transportation released a report on the susceptibility of coastal roads to sea level rise, erosion and climate change. The strip of road through Kaleo’s neighborhood of Hauula was the No. 1 priority on a list of statewide highways in need of help.

The state has been trying to fortify the road, filling it with concrete and lining it with Kyowa bags of rock, while continuing to explore long-term solutions. The highway is far from the only one at risk — the state expects that it could cost as much as $15 billion to protect all of Hawaii’s roads from coastal erosion.

Fletcher says as the ocean rises, coastal communities like Kaleo’s will be faced with an “existential transportation issue.”

ʻO nā ʻeke ʻupena nui o nā pōhaku ma o Kamehameha Highway ma Hauʻula, ʻo ia ka mea e kiaʻi i ke alanui ma ka piʻi kai ʻana.

“We already see major sections of that highway being undermined by coastal erosion. When there are heavy trade winds and it’s a high tide, we see water washing over the highway,” he said. “Given projections of continued sea level rise, this condition is only going to get worse.”

Fletcher estimates sea level is expected to rise a foot by mid-century. Even if it rises just half a foot, scientists predict there’s an 80% chance the road that Kaleo relies on will be eroded.

“If no action is taken, those roads will be impassable or unusable,” Fletcher said.

Depending on how much sea level rises, erosion could prevent residents from driving either north or south to get to dialysis, much less anywhere else.

“Over the next one to three decades, a decision really needs to be made as to whether or not we are going to commit to the continued existence of that single highway,” Fletcher said. “Or are we going to rethink what access to it from these communities looks like.”

A New Dialysis Center

ʻAtalina Pasi thinks one solution is simply to add a dialysis center closer to Hauula so that patients don’t have to make that trek. Pasi grew up less than six miles north of Hauula in Kahuku, part of a big extended Polynesian family.

Her dad is one of 13 siblings, but after Pasi graduated from college, five of his brothers and sisters died from diabetes-related complications within a span of three years.

When she later became a population health specialist, she realized that the health challenges were not unique to her family. A disproportionate number of Indigenous Pacific peoples struggles with diabetes, and for the sickest, the disease becomes all consuming: affecting what they eat, whether they can work, what work they can do.

“Being a community health worker just really opened my eyes to how this community is underserved, underrepresented, lacks so many resources,” she said. “We’re basically invisible to Honolulu.”

Hoʻomanawanui ʻo Elizabeth Kaleo i kona kaʻa no ka hoʻomaʻemaʻe koko ʻia ma Kāneʻohe.

Pasi wishes her neighbors who are dialysis patients could have access to dialysis within their own communities. So does Quinlan, her state representative.

“I’ve tried over the years to get a dialysis treatment center set up on the North Shore,” he said. “The answer that I’ve gotten is just that the economics don’t work. For whatever reason, they just can’t afford, they can’t pay for it.”

Quinlan remembers listening to a presentation from Hawaiian Electric Co. in Kahuku about how a bad storm could disable power in the community for a whole month.

“If we have a high wind event and there are power poles strewn about it could be days before our road would be reopened and it could be weeks before we get any kind of electricity,” he said. “It’s very concerning to me that we could get sort of trapped by a wind or weather event without people being able to have access to life saving treatment.”

Nephrologist Needed

Pliny Arenas, who oversees Hawaii for U.S. Renal Care, said the company is in the process of doubling the number of dialysis centers it runs statewide, but no communities on Oahu’s North Shore are on the list.

Every dialysis center needs at least one nephrologist, Arenas said, but he doesn’t know of any nephrologists in that area who would be available to direct the facility. The lack of one is why they aren’t planning a facility there.

“That’s the only reason,” Arenas said.

Fresenius Kidney Care, which runs Liberty dialysis centers, echoed Arenas’ concern about the lack of nephrologists. The company declined to say whether it has specifically considered expanding near Hauula but emphasized that helping patients access in-home dialysis and kidney transplants as well as kidney failure prevention are all potential solutions to the transportation problem.

Alan MacPhee, chief executive officer of Kahuku Medical Center, said the hospital considered establishing a dialysis center in 2015 but abandoned the plan due to concerns about how much wastewater it would generate.

About six months ago, the company started revisiting the idea after learning about a new dialysis machine that uses about half the water that standard dialysis units use. MacPhee has a meeting in a couple of weeks with a dialysis management company to explore what it would take to establish an in-patient dialysis clinic, an outpatient clinic or a program to help patients dialyze themselves at home.

Creating a dialysis center would take at least two years, MacPhee expects, given the state approvals needed and time to plan it. He’d have to find a nephrologist to run it too. But he is confident there’s a demand — in 2015, about 80 patients from Haleiwa to Kaawa were going to the Kahuku Medical Center for dialysis, and now that’s up to 130. Most are Native Hawaiian or of another Pacific Islander ancestry, MacPhee said.

“It is something that is just desperately needed up here,” he said.

There’s also the question of financing — dialysis centers are multimillion dollar operations. If the plan moves forward, MacPhee anticipates the hospital will be asking the Legislature for at least $5 million to help fund it.

That could be a tough sell, said Quinlan, who noted that Kahuku Medical Center already receives millions from the state. But both MacPhee and Quinlan agree creating a dialysis clinic is essential.

“There’s nobody in the community that doesn’t want a dialysis center,” Quinlan said. “It’s just a question of securing funding and the right organization.”

‘The Ocean Is Going To Take It Back’

At the very least, MacPhee anticipates moving forward with setting up a program to help people filter their own blood at home. Kaleo considered that when she got sick last December. But she was scared of doing something wrong, and of managing the machine alone. By going to the clinic, she knows that the blood filtering treatment will be done correctly.

She doesn’t really mind the long ride — she listens to music on YouTube, texts or reads to pass the time. She used to go to a dialysis center half an hour away from her house, but there weren’t any chairs earlier in the day and she wouldn’t get home until 10 p.m., so she switched to a center in Kaneohe. Even though it’s an hourlong commute each way, she thinks it’s worth it if she can get home by 4 p.m.

Kaleo hasn’t missed any appointments due to bad weather since she started going in December. But on her rides, she sees bags of rocks lying along the shoreline, ongoing efforts to stem the erosion and says she knows it’s a losing battle.

“Nothing can stop the ocean from taking back whatever it is,” she said. “The ocean is going to take it back.”

She’s not sure what will happen if the road is reclaimed, or when that might be, or what she’ll do then. She doesn’t plan to ever leave Hauula. She can’t imagine living in an apartment in town with no yard, away from her friends and the neighbors she’s known her whole life.

She just found out last month that she got on the kidney transplant list and is hoping that she can get an extra kidney, which would eliminate the need for dialysis.

“I just pray that God does take care of that. Some people just spend years and years and years of waiting,” she said. “And they still stay on the waiting list and never get in yet.”

Until then, she plans to keep eating well and taking her medicine and going to every dialysis appointment. Even if she has to take a bus north and all the way around the island to get to her treatment, she’s willing to do it.

“They say you cannot miss dialysis,” she said. “You got to go no matter what time you get there.”

This story was produced with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 Impact Fund for Reporting on Health Equity and Health Systems, and Civil Beat supporter Dr. Mary Therese Perez Hattori.

[This article was originally published by Honolulu Civil Beat.]