A broken system got worse: How COVID ravaged San Antonio’s South Side

This story was produced as part of USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2021 National Fellowship.

Other stories by Laura Garcia include:

Ayala: The health care system isn’t broken, it’s working as designed

Join us for a free San Antonio community health fair on May 28

Access Denied: How we analyzed the data

University Health makes plans to build two new hospitals

ACCESS DENIED: Our medical system is a maze, so patients need navigators — people like Maria Lee

Bob Owen/Express-News

City Councilwoman Adriana Rocha Garcia felt bittersweet relief when COVID-19 vaccines became available.

The breakthrough came too late for the seven family members she lost to the coronavirus, but it would certainly boost her constituents’ chances of surviving COVID-19.

It was around Christmas 2020, and San Antonio’s leaders scrambled to set up mass vaccination sites for the most vulnerable: front-line workers and the elderly. The inoculations would soon be offered to those with underlying health conditions and, several months later, to all adults.

The Metropolitan Health District established a vaccine hub at the Alamodome near downtown, while the county’s public hospital system, University Health, set up at Wonderland of the Americas, a Northwest Side shopping mall. UT Health San Antonio administered shots from its medical school campus in the South Texas Medical Center on the Northwest Side.

There would be no vaccination sites on the South Side of San Antonio.

“Not again,” thought Rocha Garcia, whose District 4 stretches across swaths of the city’s South and West sides. It would be several more weeks before the vaccine would be available at pharmacies and small clinics.

She feared that her constituents would have a harder time than most traveling to the Alamodome or farther away for the vaccine. Residents in her district are disproportionately at risk from the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2.

Rocha Garcia’s anxiety touched on a rarely discussed reality of life in San Antonio: Your health, as well as your quality of life and opportunities, are powerfully influenced by where you live.

Public health experts say place has played an outsize role in determining who contracted COVID-19 and who died from it.

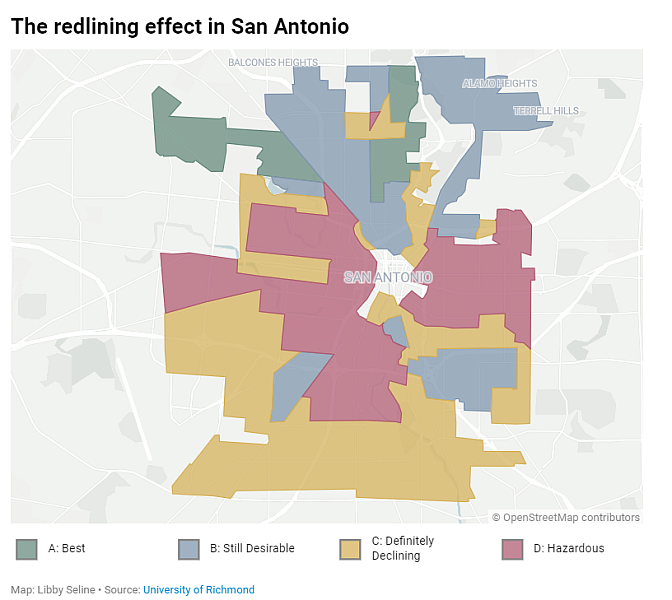

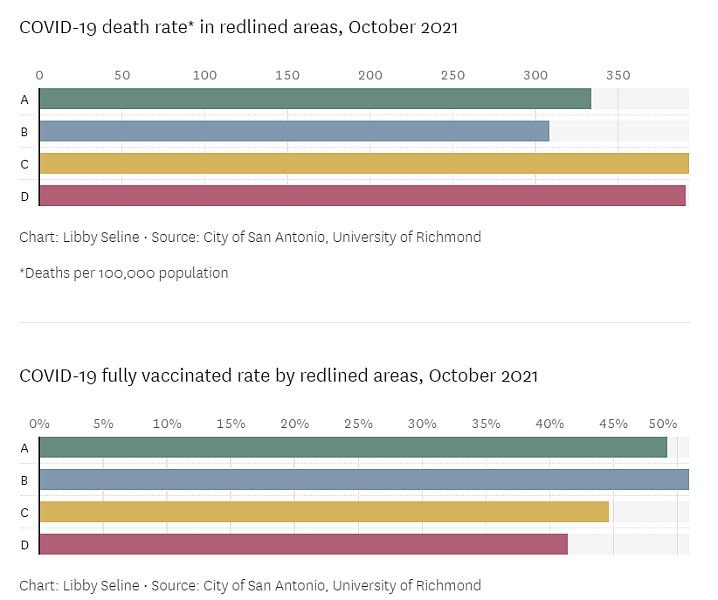

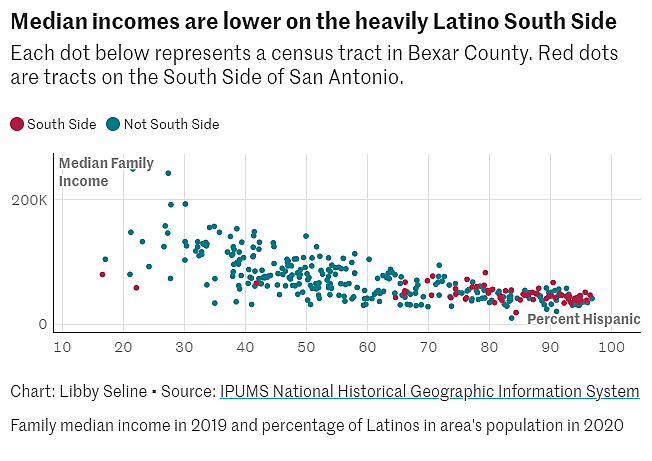

Methodology: The Express-News analyzed 50 years of census data, redlining data from the University of Richmond and information from the city's COVID-19 dashboard. Take an in-depth look at our methodology. Data analysis by Libby Seline.

Epidemiologists look at the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases per 100,000 people in each ZIP code to compare rates of vaccination, confirmed infections and deaths. Congregate settings such as jails, nursing homes, homeless shelters and military barracks are excluded from the data.An analysis by the Express-News found that COVID-19 infections have been more prevalent and more deadly among people living in the southern parts of the city, where the population is 81 percent Hispanic.

For example, residents in the 78224 ZIP code, which includes South Park Mall and Palo Alto College and has a population of 20,393, have died of COVID-19 at a rate of 677 per 100,000 people since the start of the pandemic.

2eee.jpg?itok=Ja3kXR4n)

3b5e.jpg?itok=MmZf6OtG)

f7fc.jpg?itok=kcJT-hCW)

b6de.jpg?itok=QKO6M7Wj)

Clockwise from top left: San Antonio City Councilwoman Adriana Rocha Garcia, outside her District 4 council office, lost seven members of her family due to COVID-19 five months before the first vaccines were distributed. The pandemic has been devastating for the community she grew up in and represents as an elected official. Rocha Garcia receives a sign-of-the-cross blessing from her mother, Petra Rocha, as she says goodbye to her father, Valeriano Rocha. Andrea Osorio, 47, Osorio kisses her 16-year-old son, Oscar Sanchez-Osorio, at home on the Southwest Side of San Antonio. Osorio makes café de olla for herself and Vanesa Ramirez, 53. Because of their undocumented immigration status, both women avoid seeking health care due to fear of being deported. Both work as housekeepers, putting them at increased risk of exposure to the coronavirus. (Photos by Josie Norris and Billy Calzada)

That death rate is 16 times higher than in the 78256 ZIP code on the Northwest Side, which includes The Shops at La Cantera and the University of Texas at San Antonio’s main campus and has a population of 14,074. There, the coronavirus fatality rate is 43 per 100,000 people.

The more populous 78258 ZIP code on the North Side, which has nearly 50,000 residents and includes much of Stone Oak, has a COVID-19 death rate of 232 per 100,000 people — one-third the rate of the South Side ZIP code.

Overall, the data show that poorer neighborhoods in the southern part of the city have COVID-19 mortality rates more than double that of Bexar County overall (328 per 100,000 people), the state of Texas (303), and the nation (302).

Long before the coronavirus pandemic, people on the South Side have been sicker and have had poorer health outcomes.

The reasons are cumulative and complex, starting with racially-biased government policies decades ago that intentionally pushed Hispanic, primarily Mexican American, residents into less desirable parts of the city with weaker infrastructure and less public investment — stunting the economic prospects of thousands of San Antonio families for generations.

The effects of such inequities are still visible today, leaving those who reside in the southern third of the city with less access to medical care, healthy food and opportunities for advancement.

“COVID-19 shined a harsh light on and further exacerbated systemic inequities, especially for Latinos,” said Amelie Ramirez, chair of the department of population health sciences and director of the Institute for Health Promotion Research at UT Health San Antonio.

Ramirez, an expert on health disparities, said the scientific literature suggests there is a “dose-response” relationship between social risk factors and health.

Simply put, the more social needs a person has, the higher the risk for poor health outcomes.

Crisis before COVID

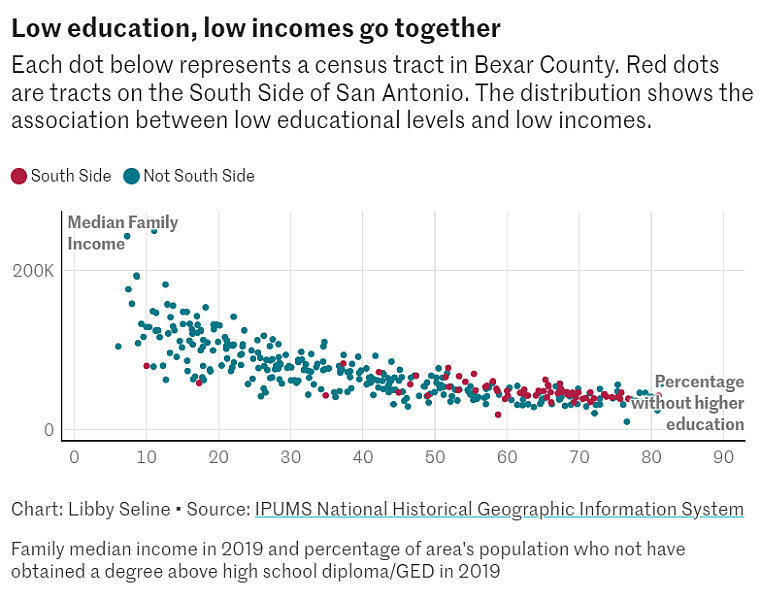

The Express-News examined certain factors — referred to as “social determinants of health” — within San Antonio census tracts to assess residents’ vulnerability to COVID-19. They include rates of diabetes and obesity, educational attainment, household income, frequency of visits to doctors and the distance to the nearest hospital.

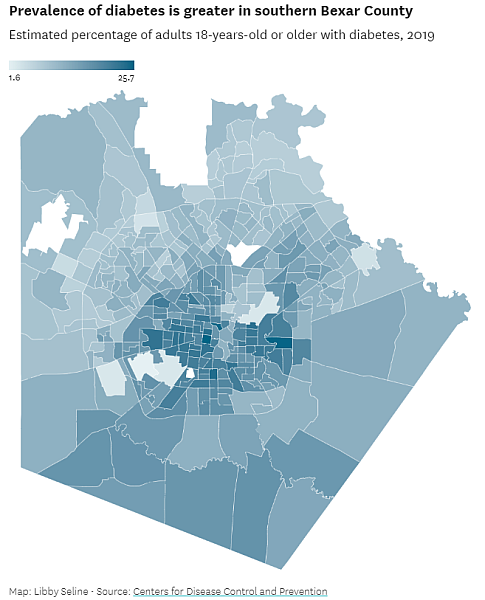

The analysis, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, found that the census tracts hardest hit by COVID-19 tend to have higher rates of diabetes and obesity, lower levels of education and substantially lower household incomes.

The most heavily affected areas tend to be farther from hospitals, and adult residents are less likely to have visited a doctor for a routine checkup within the past year.

A look at social determinants of health in two census tracts shows the role they’ve played during COVID-19.

One tract bounded by Interstate 35 South, Pleasanton Road and West Southcross Boulevard has an 88 percent Hispanic population. The median income is $35,922, and only 20.2 percent of adult residents have obtained a degree or equivalent beyond a high school diploma.

The other tract is bounded by Lockhill Selma Road, Loop 1604 and Huebner Road and has a population that is 90 percent white. The median income is $243,125 — second highest in the city — and 93 percent of adult residents have some form of higher education.

In the less affluent tract, more than 44 percent of adults are obese and 24 percent have diabetes, compared to the wealthier tract, where roughly 27 percent of adults are obese and 10.5 percent have diabetes.

Obesity is a strong risk factor for severe infection and death from COVID-19. Excess body fat can lead to cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and hypertension. Metro Health has identified those three conditions as the most prevalent comorbidities among patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in Bexar County.

The prevalence of diabetes tends to be far greater in impoverished neighborhoods. Based on 2019 Census Bureau estimates, 25.7 percent of adults living near Lanier High School on the West Side, in one of the city’s poorest school districts, San Antonio Independent School District, were diagnosed with diabetes, compared with 9 percent of adults who live in Alamo Heights, which is the city’s wealthiest school district in terms of taxable property value per student.

Close to home

In summer 2020, 15 members of Councilwoman Rocha Garcia’s family were hospitalized with the coronavirus not long after they had all gathered for Father’s Day.

Seven of them died: Paula “Pali” Castillo, Paula’s son Samuelito Castillo, Francisco “Pancho” Rodriguez, Pura Rodriguez, Gerardo “Lalo” Garcia, Martha Garcia and Ismael Rocha. They ranged in age from 38 to 78.

One of the deceased, Rocha Garcia’s favorite uncle, lived in Mexico. The rest were cousins who lived on the West Side of San Antonio, including three women who helped raise her.

Initially, she didn’t want to talk about it publicly out of respect for her family members. Weeks later, Mayor Ron Nirenberg asked her to reconsider.

“He said this is probably happening to other families, and they need to see that there’s still hope,” she recalled. “There’s an opportunity to remind them that to love their family is to take care of them by wearing a mask and by social distancing.”

She agreed. Minutes before she intended to discuss it during an online City Council meeting, she got a call from her priest, followed by an urgent text, informing her that a friend from the church had died.

“I think that was the first time I ever cried publicly,” she said. “I felt the need to tell as many people as possible so that they can protect themselves. … It was just so scary.”

In all, COVID-19 took three members of her church family from Divine Providence Catholic Church on Old Pearsall Road, not far from her district’s office and where she grew up in Indian Creek.

Once vaccines were authorized for emergency use in December 2020, she was determined to ensure that her community had access.

Rocha Garcia and three other councilwomen referred to as “the mujeres” (the women) — Ana Sandoval of District 7; Rebecca Viagran, then the District 3 representative; and Shirley Gonzales, then of District 5 — scouted places to set up vaccine sites closer to their constituents than the Alamodome, which is near downtown on the city’s East Side.

389d.jpg?itok=JQGBtDLd)

(Left) Martha Castilla visits her client Andrea Osorio in San Antonio. Castilla is a “promotora de salud” – a type of community health worker who works to provide resources in underserved, Spanish-speaking communities. (Right) Oscar Sanchez and Andrea Osorio share a laugh as they prepare dinner for their family. Oscar is a construction worker, and Andrea is a housekeeper; neither has health insurance. They seek medical care only when absolutely necessary for fear of revealing their immigration status. (Photos by Josie Norris)

Rocha Garcia said they were touring Palo Alto College’s natatorium when they learned that WellMed, which operates 10 medical clinics in Bexar County, had offered to operate two major vaccination sites for the city.

One was on the South Side, at the Elvira Cisneros Senior Community Center at 517 S.W. Military Drive. The other was on the West Side, at the Alicia Treviño López Senior Center at 8353 Culebra Road.

WellMed, a privately owned primary care provider, also staffed a phone line so that people with limited or no internet access could schedule vaccine appointments.

This felt like a win, Rocha Garcia said. But it didn’t take long for residents from across the city and beyond to jam the phone lines in search of a shot.

On the third day after the vaccine appointment hotline went live, WellMed received at least 2.5 million calls, making it hard for residents living near the senior centers to access the vaccination sites. It was an unintended consequence of setting up an open system, but it was also another obstacle for South Siders.

In another sign of stark disparities in medical infrastructure and access to health care, the first state-allocated COVID-19 vaccine doses for medical workers went to every major hospital system in Bexar County — but not to Texas Vista Medical Center, the sole hospital serving the city’s Southwest Side.

The privately-owned, 325-bed hospital lacked the freezers needed to store the first version of the vaccine. Texas Vista, formerly Southwest General Hospital, was able to vaccinate its front-line employees in those early weeks only because other providers shared their allotments.

Miscommunication

Rocha Garcia’s parents, who immigrated from Mexico, primarily speak Spanish.

She was thinking of them two years ago when cruise ship passengers stricken by COVID-19 arrived at Joint Base San Antonio-Lackland, bringing the risk of infection to the city for the first time. Rocha Garcia was present when city officials conducted a news conference — in English.

At that point, the general public knew little about the virus and how to avoid infection. It gnawed at Rocha Garcia that whatever information was available would be lost on those without a strong grasp of English.

In parts of Rocha Garcia’s district, Spanish is the primary language spoken in as many as 72 percent of households and at least 81 percent identify as Latino, according to census data.

“Nobody had delivered the message in Spanish,” Rocha Garcia recalled. When it was her turn at the lectern, she repeated her comments in Spanish. “We had people translating, but I felt it was important for someone to communicate directly in Spanish to make sure that people understood that this was very dangerous.”

Rocha Garcia, who teaches marketing at Our Lady of the Lake University, also criticized the public health department’s heavy reliance on social media in its initial communications about COVID.

“A lot of folks in my district don’t use the internet,” she said. “We’re saying all these things on social media and giving tips, but how are we communicating with them?”

In Rocha Garcia’s district, 23 percent of households do not have broadband internet access.

So the councilwoman asked city-owned CPS Energy to print the city’s COVID hotline number on customer bills. She also asked Clear Channel Outdoor to list it on billboards and church leaders to place it on their marquees and bulletins.

She then asked the city to distribute door hangers with information about the pandemic. “I was told no. And so I asked for robo-calls, and I was told no.”

She told colleagues she would do it anyway and pay for it from her District 4 council budget. She bought postcards and sent recorded messages by phone, advising residents to wear face masks, wash hands frequently and avoid crowded places.

Eventually, she said, Metro Health distributed door hangers with COVID-19 information and made a point of providing public health messages in Spanish and English.

But a year later, when it came to sending out public health communication on the vaccines, Metro Health fumbled.

A bilingual door hanger included a “translation error” on the Spanish side that incorrectly said undocumented people were ineligible for vaccination.

Undocumented

That misstep couldn’t have affected a more vulnerable population, said Martha Castilla, a “promotora de salud” — or community health worker in Spanish. She makes home visits in Spanish-speaking communities for the South Texas Area Health Education Center.

An estimated 151,000 foreign-born individuals in San Antonio are potentially at risk of deportation, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. The vast majority are Hispanic or Latino and have lived and worked here for years. Many are reluctant to ask for help for fear it could expose their undocumented status.

They can be among those who need help most and are least able to access it. Such families, for example, did not qualify for the federal COVID-19 stimulus payments that kept others afloat during the pandemic.

Castilla met recently with two undocumented women — Andrea Osorio and Vanesa Ramirez, who also is a promotora de salud — at Osorio’s home on the South Side. Over cups of café de olla, a sweetened coffee drink, they discussed their difficulties accessing health care and coping with COVID-19.

Osorio, 47, from Mexico, doesn’t qualify for CareLink, a financial assistance program offered by the county hospital. And she doesn’t want to risk applying for Medicaid for her children because of the risk of a federal crackdown on undocumented applicants.

“I tried to buy health insurance, but you need a Social Security number,” she said.

Andrea Osorio recounts her experiences as a survivor of domestic abuse and emigrating from Mexico to give her children a better life. Josie Norris / San Antonio Express-News

A wall across from a large wooden dining table is decorated with a hand-painted mantra in Spanish: “Siembra pensamientos cosecha resultados.” Osorio said it translates roughly as: “Everything you think (positive or negative) will be the results in your life.”

Ramirez, 53, fled Nicaragua 19 years ago. She says she wouldn’t feel safe returning. When she was a girl, her mother was abducted and her father killed because he worked for the Somoza government when it was overthrown by revolutionaries in 1979.

Ramirez, who has worked as a housekeeper and nanny, doesn’t want to do anything that would call attention to her immigration status because it could result in her being separated from her family. Her husband, daughter and three grandchildren are U.S. citizens.

She said that like most of the women she assists as a promotora, she skips regular medical and dental treatments.

Front-line workers

Osorio works seven days a week cleaning houses.

When hundreds of thousands of San Antonians were hunkered down in their homes to avoid the coronavirus, women like her had no choice but to go into other people’s houses.

Census Bureau data shows that people who live on the South and West sides of the city are far more likely to work as maids, cashiers, cooks, janitors, home health aides, retail salespeople and restaurant servers — public-facing jobs with a higher risk of exposure to the coronavirus.

Fewer than 1 in 6 Latinos nationally were able to work from home during the pandemic, compared with 1 in 4 white workers.

“Many of our marginalized communities were not really in a position where they could actually just stop going to work because they didn’t have the opportunity to work remotely,” said Jason Rosenfeld, an assistant professor of global health at UT Health San Antonio.

Rosenfeld leads a federally funded initiative called Health Confianza for Metro Health focused on improving health literacy in 22 ZIP codes in the city.

One of those ZIP codes is 78242 on the Southwest Side, where Osorio and her family live.

She made sure to get vaccinated but suffered a breakthrough infection after her youngest son contracted the virus at school. She missed work for a week without the benefit of paid sick leave.

Osorio paid out of pocket to be seen at a clinic on Southwest Military Drive that markets itself to Hispanic consumers. She checked in every two days to make sure her oxygen levels were satisfactory so she didn’t have to go to the hospital.

Osorio’s household includes her husband, an 11-year-old, a 16-year-old, an adult daughter who is a teacher and Osorio’s 75-year-old father, who works outside the home.

Castilla, the promotora, said undocumented immigrants aren’t the only people who fall through the cracks. She is board president of Edgewood ISD on the West Side, where she co-founded a nonprofit to help families access health care, overcome educational barriers and cope with domestic violence.

Castilla learned that one student came home from school to find her mother had died of COVID-19.

Dr. Jason Morrow, a hospice and palliative medicine specialist who treats terminally ill COVID-19 patients at University Hospital, said the pandemic revealed problems in the health care system.

“This crisis occurs in the setting of an existing crisis, … making a broken system worse,” Morrow said. “It managed to deepen the fault lines between the haves and the have-nots.”

Morrow, an associate professor at UT Health San Antonio, and his team have now worked through four major surges in hospitalizations. They were often the ones holding the hands of patients as they died from the virus. Most were Hispanic.

Latinos are 61 percent of Bexar County residents. According to Metro Health, among cases in which race and ethnicity data were available, Latinos accounted for 70 percent of the county’s COVID-19 cases and 67 percent of deaths.

Born & Raised

Dr. Ray Altamirano practices family medicine at Casa Salud, a primary care clinic he founded on the South Side, where he grew up as the son of Mexican immigrants.

Patients at Casa Salud pay $100 per visit, a flat fee that includes basic lab work. Altamirano doesn’t accept insurance, saying it’s his way of pushing back against a “broken” health care system that caters to the rich and fails the poor.

His mother worked at a Levi Strauss Inc. jeans factory until it closed abruptly in 1990 when the company moved production to Costa Rica. His father owned a meat market. He and his siblings made barbacoa and chicharones on weekends to sell at the store — his parents’ way of instilling a strong work ethic.

c812.jpg?itok=5em5XZm-)

fb25.jpg?itok=QiG4NV1a)

Dr. Ray Altamirano displays paintings he created on the walls of Casa Salud Family Medicine Clinic, which he founded on the Southwest Side, where he was raised. The clinic allows patients to pay a flat $100 fee for each visit regardless of insurance status. Meanwhile, Altamirano sells his art to help patients who can’t afford medical care. Many patients, he said, would otherwise “fall through the cracks” and have exhausted other local financial aid programs. He also works nights at a freestanding emergency care center on the Southeast Side. (Photos by Josie Norris)

Altamirano was valedictorian of Harlandale High School’s class of 1998. After earning a medical degree from Universidad Autónoma de Guadalajara in Mexico, through a program with New York Medical College, he decided to open a clinic in his old neighborhood, where he believed he could make the biggest difference.

“I’m 78214 born and raised,” he said.

His practice at Casa Salud has shown him the pandemic’s long-term effects on people’s lives.

For patients who survived the virus, its lingering effects prevent them from supporting their families as they did before. Some can’t afford certain treatments for COVID-induced conditions.

One patient, a roofer, suffered shortness of breath for six months after contracting COVID — so he lost his job.

A patient with diabetes survived COVID but no longer responds to medication to lower blood sugar. The patient now depends on insulin to survive.

“There’s odd things happening to them that I can’t explain,” Altamirano said, “and I’m seeing it much more in my unvaccinated patients.”

He’s describing “long COVID” — the lasting side effects that an estimated 23 million Americans experience after recovering from the coronavirus.

Altamirano also worries about misinformation surrounding COVID vaccines. He said it breeds mistrust in medicine, which could be very damaging to people on the South Side, where many are predisposed to suffer from diabetes, obesity and other conditions.

“In the beginning, they said ‘flatten the curve,’ but that requires resources and we already had none,” Altamirano said. “Flattening the curve is a lot different when you’re talking about Stone Oak versus here. There’s so much more chronic illness here.”

_0f625.jpg?itok=vjPb3DwR)

Laura Garcia reported on health disparities as a USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism 2021 National Fellow and a grantee of its Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism.

Data reporter Libby Seline and business reporter Diego Mendoza-Moyers contributed to this article. Assistant city editor Tony Quesada edited the series. Digital presentation by Chris Quinn.

[This story was originally published by San San Antonio Express-News.]