A World Of Hurt: The Link Between Domestic Violence And Community Gun Violence

This project was originally published in The Observer with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism‘s Domestic Violence Impact Reporting Fund.

The Observer

Arizona prosecutors say Dandrae Martin beat, choked, stomped and urinated on his girlfriend for an hour, in front of their two small children in 2016 because she refused to let him prostitute her. In 2018, his brother Smiley Martin pled guilty to assaulting his own girlfriend, whom he encouraged to prostitute. In a prolonged attack, Smiley beat her with his fists and a belt until she was covered in blood.

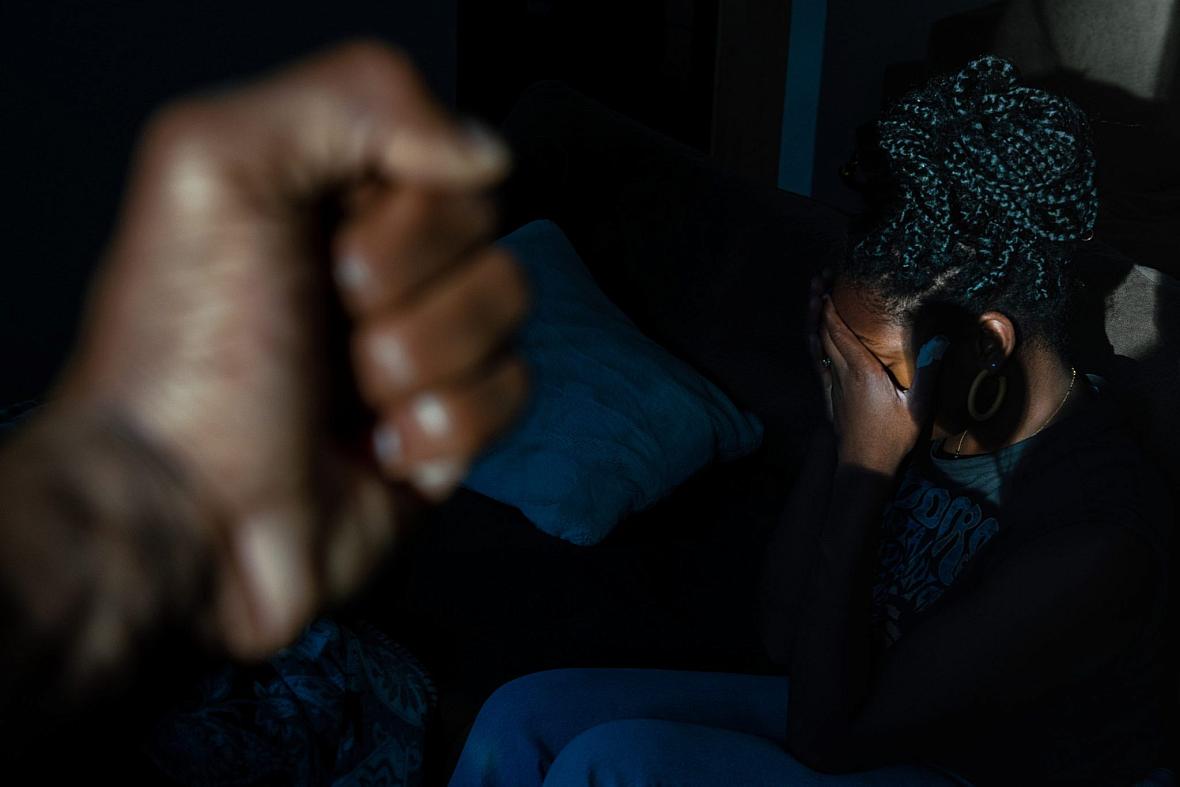

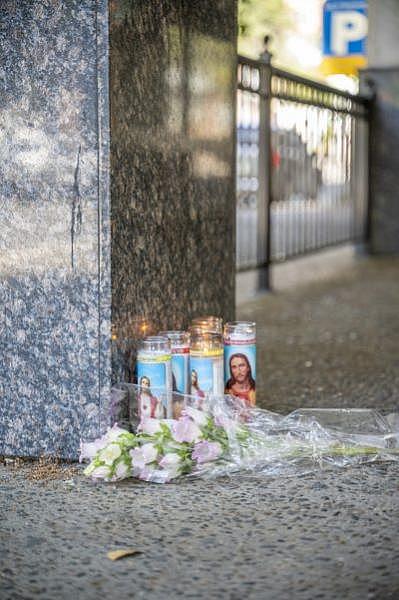

Deadly mass shootings, such as the one on April 3 on K street in downtown Sacramento, have made national news. Area advocates and stakeholders say that often left untold or underreported is a story behind the story. Before assailants commit heinous crimes and take innocent lives in public, they often display violent behaviors at home. Russell Stiger Jr., OBSERVER

The Martin brothers are suspects in a deadly shooting that occurred in downtown Sacramento this past April. When Mtula Payton was named as a third suspect and rival shooter in the incident that claimed six lives, law enforcement already was looking for the 27-year-old on multiple felony warrants, including domestic violence and gun charges.

According to the Sacramento Police Department, Payton’s warrant for felony domestic violence stemmed from an April 2 altercation in which a woman claimed he’d injured her.

Several deadly mass shootings, including the one in Sacramento, recently have made national news. Area advocates and stakeholders say that often left untold or underreported is a story behind the story. Before assailants commit heinous crimes and take innocent lives in public, they often display violent behaviors at home.

There is significant overlap in the factors that drive domestic violence and those behind community gun violence, such as trauma, mental health issues, and poverty and other socioeconomic inequality. Advocates and law enforcement officials say paying closer attention to abusers and limiting their access to guns could help prevent future firearm injury. Experts are also calling for a more comprehensive study of the intersection between domestic violence and other gun-related crimes.

Nearly 60% of mass shootings that occurred from 2014 to 2019 were domestic violence related. In more than 68% of those shootings, the perpetrator either killed at least one intimate partner or family member, or had a history of domestic violence, according to a recent Johns Hopkins University study. Though perpetrators of mass shootings tend to be White, researchers say there’s also a link between patterns of domestic violence and urban gun crime perpetrated by African American men.

Smiley Martin was released from prison in February, having served nearly half of a 10-year sentence for domestic violence. His release came just two months before police say he brought a machine gun to downtown Sacramento and opened fire on a crowd exiting a nightclub. When the younger Martin brother was first up for early release in May 2021, the Sacramento County District Attorney’s Office wrote a letter urging the parole board not to let him out, saying he posed a “significant, unreasonable risk of safety to the community.”

An Urban Issue

Local community advocate and mentor Berry Accius says the intersectionality between domestic violence and urban violence doesn’t garner a lot of attention.

“More or less when you look at the homicides, especially for Black women, it’s happening because of the person that they’re dealing with. It’s a sibling, or a boyfriend, someone they’re dating randomly or someone that they’re meeting,” Accius said. “It falls into line with some of the violence that we’ve watched occurring across the nation and especially locally here in Sacramento.”

In January, Accius called for an end to violence after 17-year-old Alynia Lawrence was fatally shot while sitting in car a near Stockton Boulevard, on a stretch of road known to be frequented by prostitutes and young girls who are being trafficked. In 2020, he and other leaders demanded answers in the mysterious death of another Black woman, Taylor Blackwell, 19, found dead in a South Sacramento motel.

“The gun violence that I deal with, the domestic violence that I deal with, they’re almost the same bird,” Accius said. “It’s just looked at differently because everybody wants to center gun violence on just gangbanging and gang culture. They don’t want to look at gun violence and domestic violence.”

Accius said law enforcement should be able to ensure that people with histories of domestic violence can’t access firearms.

In motions filed by the local district attorney, at least two of the accused shooters in the K Street case have enhanced gun charges because of violations tied to prior felony domestic violence convictions.

Focus Area

Local and national researchers agree that there needs to be more study on the link between domestic violence and violence in the Black community, and that law enforcement should be more proactive about flagging domestic violence perpetrators as potential future participants in gun crime.

Dr. Shani Buggs, an assistant professor of emergency medicine at UC Davis, studies gun violence prevention programs and policies, and gun violence in communities of color.

“The drivers can often overlap with the thinking about economic strain, the stress and trauma, the complex traumas that come from living in low-income communities with high rates of violence’” said Dr. Buggs, a researcher in the university’s violence prevention research program. “There are definite correlates but, again, not much formal research.”

The way community violence is discussed and reported on has shifted slightly, the UC Davis researcher says, largely by the insistence of advocates and survivors.

“There have been huge efforts on the ground in these communities to be heard, to be seen, to be taken seriously,” Dr. Buggs said. “Violence has been treated as if it’s just going to happen in the Black and Brown communities and then it’s a shock when it happens outside of those communities. That’s structural racism. That’s White supremacy.”

Violence deserves attention regardless of where it takes place, she said.

Finding good data on intimate partner violence or domestic violence arrests and convictions can be challenging. “You need that individual-level data to be able to link homicides or nonfatal shootings to the individuals’ histories, their violent histories, and that’s difficult data to get from most law enforcement agencies,” Dr. Buggs said.

Deputy District Attorney Dawn Bladet, who oversees the county district attorney’s domestic violence unit, confirmed as much. “We do not keep statistics on acts of community violence and perpetrators’ history of domestic violence,” she said.

“We have seen in some cases, like the recent shooting in downtown Sacramento, which claimed multiple lives, that there can be a correlation between the two. All shooters in the incident had a history of beating women.”

Timiza Wash, director of community engagement strategies for WEAVE (Women Escaping A Violent Environment) says domestic violence often is viewed as a cultural norm in the Black community. This only compounds things, Wash says, for a race of people already experiencing other trauma.

“It’s time for some healing,” she said.

WEAVE has been doing healing work through its Healthy Black Families Collaborative, which seeks to reduce domestic and sexual violence in South Sacramento, Meadowview and Valley Hi. A series of listening sessions helped provider partners hear directly from community members about their experiences and needs.

Then COVID-19 hit, bringing with it a new set of issues.

“With the onset of COVID we saw in general that gun violence was at an all-time high, the unemployment rate was at an all-time high and domestic violence was at an all-time high,” Wash said. “Those added much trauma to what was already existing for people. Not having the choice to go out when we were sheltering in place and then abusers and survivors being in the same home and not having choices as to what to do.”

Hurt People Hurt People

Isolation, depression and existing socioeconomic conditions have been explored as contributors to domestic violence. Additionally, individuals who harm often reveal that they are survivors of violence themselves.

According to the U.S. Department of Justice, almost 1 in 10 American children saw one family member assault another family member, and more than 25% had been exposed to family violence during their life. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention calls community violence a “critical public health problem” with physical, emotional and financial ramifications.

Growing up in a home or neighborhood with high exposure to violence has been linked to higher rates of weapon possession. In 2017, a study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine found that those who witnessed violence had 43% to 59% higher odds of gun possession and those who experienced violence had 63% to 87% higher odds of gun possession.

Dr. Buggs is interested in exploring the relationship between previous trauma and future trauma. “One of the strongest predictors of future violence is exposure to prior violence,” she said. “And if we know this, then what we need to be doing is responding to that first violent incident and responding in a way that is focused on healing and focused on addressing the traumatic incident and resolving the trauma.”

“Trauma begets trauma,” Dr. Buggs said. “Research needs to be doing a better job of illuminating that and also putting pressure on leaders and systems to respond earlier and sooner because violence is preventable. Violence is a symptom of the larger, deeper issue.”

Dr. Buggs and others said getting to the root of why domestic violence occurs is key to finding solutions to it and related community violence.

Asantewaa Boykin, an area emergency room nurse and co-founder of the Sacramento- and Oakland-based Anti-Police Terror Project, said violence is learned behavior emulated from America’s ruling class. Those who don’t value themselves will see that self-hatred reflected in their familial relationships, Boykin said. Violence, domestic or otherwise, isn’t something she sees being eradicated.

“We can definitely create the conditions where we’re not as likely to hurt someone who we’re in a familiar relationship with. That means addressing the culture,” Boykin said.

“That means addressing the generational trauma, addressing domestic violence and addressing our own inferiority complexes when it comes to a White supremacist system. So that will also mean actively dismantling White supremacy.”

Paméla Tate, co-executive director of San Francisco-based organization Black Women Revolt Against Domestic Violence, has explored the topic in her work, stressing the need for cultural responsiveness in domestic violence shelters.

“It goes back to intergenerational trauma, which can be attributed to community violence, domestic violence, and post-slavery as well as slavery,” Tate said. “A lot of our experiences are a retraumatization of things that our families have experienced intergenerationally.”

Something Has To Give

Locally, Accius and his team created monthly discussions called Brother, Can We Talk? and MOB (Motivating Other Brothers), and youth development programming like Real Teen Talk on TikTok to deal with mental health and a myriad of other topics that impact the lives of young people.

“We try to find a place where people can release that energy, that negativity, and feel safe to have a conversation,” Accius said. “A conversation about what makes it tick like a time bomb and how we can give them tools and the ability for when they don’t have a safe space, so they can stop from making a fatal mistake that will cost them their lives as well as somebody else’s.”

It’s all hands on deck, Accius said. “No one person has the blueprint on how to fix it. (If they did), they would have sold it all,” he said. “At the end of the day, we’ve got to get back to the village mentality.”

As debate continues on everything from what contributes to community violence, to the need for harsher sentencing, Accius is among community advocates trying to stand in the gaps. He believes in second chances, having received one himself, but says it’s time to get real and do something different about the havoc that violent actors wreak in the Black community.

“We can’t sit here and keep on allowing women to be killed in this way,” he said. “If we don’t create those things in place — if there’s not a cousin, if there’s not an uncle, if there’s not a father, if there’s not a big homie, a guy that they can sit there and say, ‘Hey bro, you’re tripping, let that girl go be herself’ — then yeah, it’s going to have to come from an outside source.”

Accius said domestic violence offenses lack appropriate consequences and that “slaps on the wrist” serve no one. The system, he continued, often fails young Black men like the Martins and Payton, whom police have tied to area gangs.

“The system didn’t have anything in place before they became who they became, before they became victims of the system,” Accius said. “They didn’t replace that with any mentoring programs and things of that nature.”

“If there’s nothing in place to rehabilitate young men and young women out of this center of chaos, then what do you expect them to do?”

A Different Approach

In the past two years, since the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and others, there have been demands for local governments to defund or restructure police spending. Activists also have called for the removal of law enforcement from mental health and domestic violence situations, where their presence can escalate matters, often tragically.

In February 2001, a 33-year-old Black father, Donald Venerable Jr., was killed by Sacramento police responding to a domestic dispute between him and his wife. A police officer mistook a cell phone Venerable withdrew from his pocket for a handgun.

Following recent police-involved deaths across the country, some Blacks are flat-out scared to call 9-1-1 in situations involving domestic violence and intimate partner violence. They started calling relatives instead and relying on community groups such the Anti-Police Terror Project, who offer support through their Mental Health First service.

“We say, ‘We’ll help you plan.’ I really think that was it,” Boykin said. “When we said ‘domestic violence,’ we had very few domestic violence calls, but when we kind of changed the lingo to domestic violence safe planning, it changed because people were like, ‘So what is this plan? What are we gonna do?’”

Mental Health First volunteers aren’t first responders in domestic violence or intimate partner violence situations. That work is too dangerous for civilians. On the flip side, San Francisco’s Black Women Revolt Against Domestic Violence is funded by efforts to “defund” the police.

“San Francisco city and county took money back from the police department last year and gave a lot of that money to community resources through their human rights commission,” Tate said. “We are one of the first to receive some of that funding to start our organization.”

Police aren’t trained to handle every situation, she said. The state of California requires 40 hours of training for someone to be certified as a domestic violence advocate. In San Francisco, Tate said, officers have less than 30 hours of domestic violence training.

“[Officers] are the first people to respond in a domestic violence situation, which is why it’s one of the most lethal situations that a police officer can walk into,” she said.

While some in the community would remove law enforcement from domestic violence response, Bladet, of the county district attorney’s office, said advocates, lawyers and law enforcement are working together with an emphasis on educating people about prevention of recurrence and escalation to other community violence. As head of the Sex Crimes and Family Violence Bureau, Bladet serves as vice chair of a domestic violence prevention council, which aims to form systemic, multidisciplinary change and to improve public safety.

Bladet also heads a domestic violence death review team, a subcommittee of the Sacramento County Domestic Violence Coordinating Council that presents its findings to the county board of supervisors.

“The team meets monthly to debrief domestic violence-related homicides and murder-suicides with the goal of providing evidence-based recommendations regarding the needs for services and intervention in domestic violence in Sacramento with the goal of reducing the number of these tragic deaths,” Bladet said.

Sweep Around Your Own Front Door

Police violence is a daily topic of discussion in the Black community and rightfully so, but local advocates and activists said a bit of self-reflection is also due.

“The accountability part of our community is going out the window,” Accius said. “We don’t want to pick up the shovel to do all the dirty work. It’s easy to say, ‘Stop killing us.’ It’s more difficult for us to start saying that with ourselves because most people are OK with that. Most people are OK with taking out their opps. Generally, you can’t find a city that’s all Black in America that’s not in some type of chaos. And that’s not the outside things that have taken effect. It’s all the inside things.

“A White man isn’t there when a Black man is abusing a Black woman, so how did he cause that? We could say, well, it’s because of this or it’s because of that, but we do have to start making decisions of our own and being accountable.”

Black women need to be valued more, Accius said, by Black men and by society in general. Until they are, he said, abuse against them will continue to be ignored as a warning sign of future violence, resulting in missed opportunities to avoid that violence.