Why one of Clark County’s largest mental health providers is juvenile justice system

The Las Vegas Sun spent several months exploring community challenges created by lack of treatment for children with mental problems. Jackie Valley reported this story for the Sun as a 2015 National Health Journalism Fellow, a program of the University of Southern California's Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

Other stories in the series include:

How Nevada struggles to help children battling mental illness

In Nevada, mental health crisis among children merits a closer look

In Las Vegas, parents, doctors and mental health advocates talk pediatric challenges

‘The polio of our generation’: Mental health troubles often land kids in emergency rooms

Judge William O. Voy in his courtroom on October 15, 2015.

Three cases down and a dozen more to go, Judge William Voy surveys the movement below his bench on a Monday afternoon.

It’s late August. The fourth defendant on his calendar — a 13-year-old boy wearing an orange T-shirt and navy blue sweatpants — enters from a side door connecting Clark County’s Family Court to the juvenile detention center. He’s no stranger to Courtroom 18.

His name rings familiar to the probation officers, attorneys and clinical staff, some carrying files or toting bulging bags, who are positioning themselves in front of the judge. Colby, whose name has been changed for this story, first appeared before Voy in January after an alleged home invasion. The case wound up in “Youth Mental Health Court,” where the children’s mental health needs generate more discussion than their alleged crimes.

Today will be no different.

Colby has autism and related cognitive difficulties, as well as behavior disorders. Since May, he has landed in University Medical Center’s pediatric emergency department 25 times as a patient, which is why Dr. Jay Fisher is standing before the judge too.

“Thank you, judge, for letting me speak in your court,” says Fisher. He is speaking on behalf of the Children’s Hospital of Nevada at UMC. “We have been trying our best to help … keep (Colby) safe. And we feel we have failed in that regard.”

He’s speaking calmly, but his words are tinged with emotion. He has never before requested to speak in court. But Fisher says he’s worried — frightened, really — that if Colby doesn’t receive better mental health treatment, the teen will endanger his own or others’ lives.

Colby has been accused of running recklessly through the streets, throwing rocks at vehicles and attempting to harm his mother. Several times, authorities transported him to the hospital under the auspice of a “Legal 2000,” in which a person deemed a risk to himself or others can be detained.

“If something were to happen to him, I don’t know what I would do,” the doctor says.

“I understand what you’re saying and how genuine your feelings are,” the judge responds.

The case represents a gaping hole in the community’s ability to care for children with the most severe emotional and behavioral needs.

Sometimes there’s no good place for them to go. So the children who need medical care end up in court.

• • •

Inside the sprawling Family Court building north of downtown Las Vegas, judges finalize divorces, approve adoptions and make custody decisions. They also preside over cases involving some of the community’s youngest offenders.

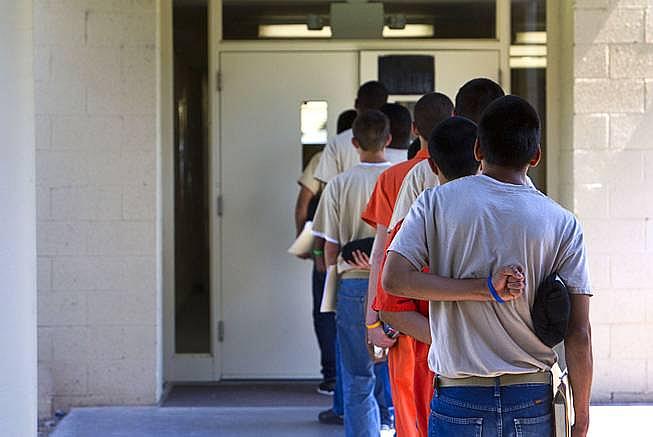

Last year, the Department of Juvenile Justice Services had contact with 9,164 children and teens, nearly a third of whom were taken into custody.

Steve Marcus - Teens head to class at C.O. Bastian High School in the Caliente Youth Center in Caliente, about 150 miles north of Las Vegas, Tuesday, Sept. 8, 2015.

Most juveniles’ brushes with the criminal system involve a misdemeanor offense, such as battery, possession of marijuana or petty larceny. Some children and teens were cited or charged more than once, leading to 14,082 total referrals in 2014. (Black youths are overrepresented among juvenile cases, while white youths are underrepresented.)

Many of these juvenile offenders have something in common: mental illness. State officials say as many as 70 percent of adolescents in Nevada’s juvenile justice system have a mental disorder — a prevalence rate that mirrors most national estimates.

“(It) troubles me that our detention facility is the largest mental health hospital in the state for juveniles,” said Jack Martin, director of Clark County’s Department of Juvenile Justice Services. For the past two years, the juvenile detention center has housed roughly 130 youths per day.

Caring for children with mental health problems doesn’t solely fall on their parents or guardians. The responsibility spills into schools, hospitals and — sometimes — the juvenile justice system. If children’s emotional and behavioral problems escalate, their chances for committing a delinquent act increase as well. The juvenile justice system, then, becomes the backstop.

That’s why most detained children and teens receive a mental health evaluation right off the bat, said Cheri Wright, manager of clinical services for the Juvenile Justice Services. In recent years, her staff has grown to 18 clinicians who provide assessments, case management, crisis intervention and counseling, among other services.

Their goal: Identify youths entering the system who need mental health services to curb the problem before it balloons into something larger.

“Mental illness is not a new thing,” Martin said. “We’re better at finding these root causes of criminality than we were 25 years ago. Now, we are getting better at connecting these children to the appropriate resources.”

Trauma can contribute to mental health problems. The juvenile justice system routinely receives children and teens who have been abused and neglected. Many have grown up surrounded by violence or witnessed a traumatic event, such as a loved one committing suicide. Post-traumatic stress disorder is a common diagnosis, along with depression and anxiety. In lieu of professional help, many adolescents have self-medicated with alcohol and drugs, leading to dual diagnoses.

It is critical to understand how a child’s past events may be influencing his or her emotions and behavior, experts say, because it can be a predictor of health outcomes. A landmark study published in 1998 by Kaiser Permanente suggested that as the number of traumatic childhood experiences increases, so does a person’s risk for poorer health later in life.

County officials hope that if and when a proposed assessment center comes to fruition, it would help identify children’s needs even earlier. It would create a central, physical location where children who have interacted with law enforcement can be brought for an assessment of their needs as well as their family’s. Are they homeless? Do their circumstances warrant investigation by child welfare workers? Do they have mental health issues?

A number of community partners — including law enforcement agencies, the Clark County School District, Department of Family Services and Juvenile Justice Services — have signaled interest, Martin said. But money remains the barrier.

• • •

“The sooner you diagnose mental health issues, the more likely you’re going to get the early intervention you need,” Voy says. “But if you allow it to fester, you may see my courtroom.”

And it’s a busy courtroom. His Monday afternoon calendar, largely set aside for mental health-related cases, can stretch several hours as attorneys, probation officers, family members and community providers weigh in on the child’s mental health, progress and setbacks — sometimes without even mentioning the criminal charge. In recent weeks, the Monday calendar has averaged 25 cases.

During one session, a detained 11-year-old girl admits to kicking family members. Her defense attorney says she becomes violent when she’s not on her psychotropic medications. Several cases later, a mother appears before Voy with an update about her son, who was in an out-of-state residential treatment center. She says doctors were adjusting her son’s medications for attention deficit disorder, autism and bipolar disorder, hoping to quell his recent auditory hallucinations.

In a different case, Voy requests that a boy’s therapists remain the same for “continuity of care.” The boy witnessed a murder and was enrolled in trauma-oriented therapy. He’s sitting in a chair, his head not much taller than the table in front of him. The boy had been removed from his grandmother’s home because of his aggressive behavior.

As the afternoon wanes, Voy calls the 15th case on his calendar. A heavyset boy wearing jeans and a short-sleeved shirt entered the courtroom with his parents. He smiles and gives his defense attorney a friendly fist bump.

Several weeks earlier, the boy slapped his mother in the ear. He’s now receiving in-home therapy aimed at controlling his aggression, and his mother says it’s going well.

“It sounds like all the services we have are there,” Voy says. “It’s just a matter of whether it works.”

Will it work? That’s the question haunting so many justice system employees, like Voy, who interact daily with these children and teens. If intervention fails and their mental health problems worsen, the judge knows they likely will end up back in his courtroom — or an adult courtroom.

• • •

Once a month, Dr. Norton Roitman drives 2.5 hours northeast of Las Vegas to the quiet, old railroad hub of Caliente. He travels past cottonwood trees and eateries with names like Pioneer Pizza and the Brandin’ Iron Restaurant en route to the town’s densest collection of temporary residents: Caliente Youth Center.

Steve Marcus - Psychiatrist Norton Roitman poses at the entrance at the Caliente Youth Center in Caliente, Nev., about 150 miles north of Las Vegas,Tuesday, Sept. 8, 2015.

As a child and adolescent psychiatrist, his medical prowess is needed here. At the base of a rugged hill, a collection of circular buildings houses up to 140 boys and girls, ages 12 through 18, many from Clark County.

Nearly 40 percent of the adolescents court-ordered to Caliente Youth Center, a state-run juvenile correctional center, take medications for mental health-related problems. For two days, he talks with dozens of patients.

As Roitman sits behind a wooden table at the on-campus school, his second patient of the day enters: a smiling, 16-year-old girl. Her curly hair is pulled back into a ponytail.

“It’s a big decision to see a psychiatrist, isn’t it?" he asks.

“Yes, it’s a little scary,” she replies, laughing nervously.

She initiated the psychiatric evaluation after recent bouts of crippling anxiety and frequent nightmares. She had been cutting herself too. As she speaks, her cheerful demeanor fades.

“It’s like I don’t even think about it,” she says. “It’s like my brain just tells me to do it. When I realize what I’m doing, it’s already done.”

Roitman gently prods for more details and, soon, a clearer picture of the girl’s complicated life emerges: Her parents divorced when she was young. Her father, a drug user, is her rock. She swallowed pills as a pre-teen in a suicide attempt. She’s dabbled in drugs too, mostly as self-medication to make her happy. But it hasn’t worked. She watched a relative overdose on drugs and die. She blames herself for everything.

“Do you think there’s a chance you would actually go through with (suicide)?” Roitman asks.

“Yeah, it could happen,” she says.

She reaches for a tissue as her eyes well up with tears. A half hour passes as Roitman lets her talk — and sob — intermittently. Then he brings her back to the present with this question: “Do you ever imagine that things will turn out OK?”

She rejects the idea at first, then waffles and says, yes — maybe — if she graduates. She doesn’t want to keep living day by day. Or make another poor decision, like robbing homes, that led to her detainment at Caliente Youth Center.

“With more clarity of thought and ability to expressing feelings … you could find some sunlight and relief,” Roitman says. “You could wind up daring to believe that something positive could happen.”

He prescribes a medication that should help her sleep immediately and lessen her anxiety and depression over time. What he doesn’t do: tell her a diagnosis, which she could cling to, or prescribe a powerful anti-anxiety medication, such as Xanax.

Roitman wants the adolescents at Caliente Youth Center to find the inner strength to work through their problems — often caused by environmental factors like poverty, drug use or family dysfunction. He wishes society would do the same and address the root causes of mental illness.

“I’d like them to think it’s a little more complicated than, ‘Do they have ADD, bipolar, autism or depression?’” he says. “These psychosocial factors aren’t just tossups.”

It pains Roitman when the children ask to schedule another time to talk. With a list of 40 children to see on this day alone, regular counseling sessions aren’t possible. His visits to Caliente are more medication-oriented. He assesses their psychiatric state, prescribes medication if necessary and monitors its effects.

The youth center has struggled to staff mental health workers, partially because of its remote location, but it now employs four counselors. Still, their caseloads are too high to provide regular, individual counseling.

• • •

When Dr. Fisher visited Voy’s courtroom, he offered a recommendation: Don’t let Colby go home, where he likely would engage in more violent behavior. It was an uncommon request given efforts to keep children in the community — and preferably at home — but it boiled down to safety.

“It’s our job as pediatricians and emergency physicians to care for our patients and to state when something is wrong,” he told the judge.

Voy knew it was a tall order. These type of cases don’t always fit Medicaid reimbursement criteria, and residential treatment centers, most of which are out of state, had denied Colby in the past. Many psychiatric hospitals that provide long-term care don’t accept children who have a low IQ and behavior disorders. On top of that, Colby’s family wanted him to come home. And so did Colby.

Even so, the clinical services staff inquired about residential treatment centers again. A week later, they returned with the same answer: No one was willing to take Colby. The teen went home, leaving the judge and the physician worried about his future well-being.

Several weeks later, Fisher brought up his fears concerning Colby during a task force meeting he leads. The judge attended as well as people who work for the schools, hospitals, police departments and mental health agencies. The group urged a state official to consider adding beds at Desert Willow, the state-run psychiatric hospital, for children like Colby who are falling through the gaps.

“That’s just a good example of where our system has failed,” Voy said later.

At the end of November, Colby ended up back in the juvenile detention center after another outburst at home — just as they had feared.

[This story was originally published by The Las Vegas Sun.]

Photographs by Mikayla Whitmore/The Las Vegas Sun.