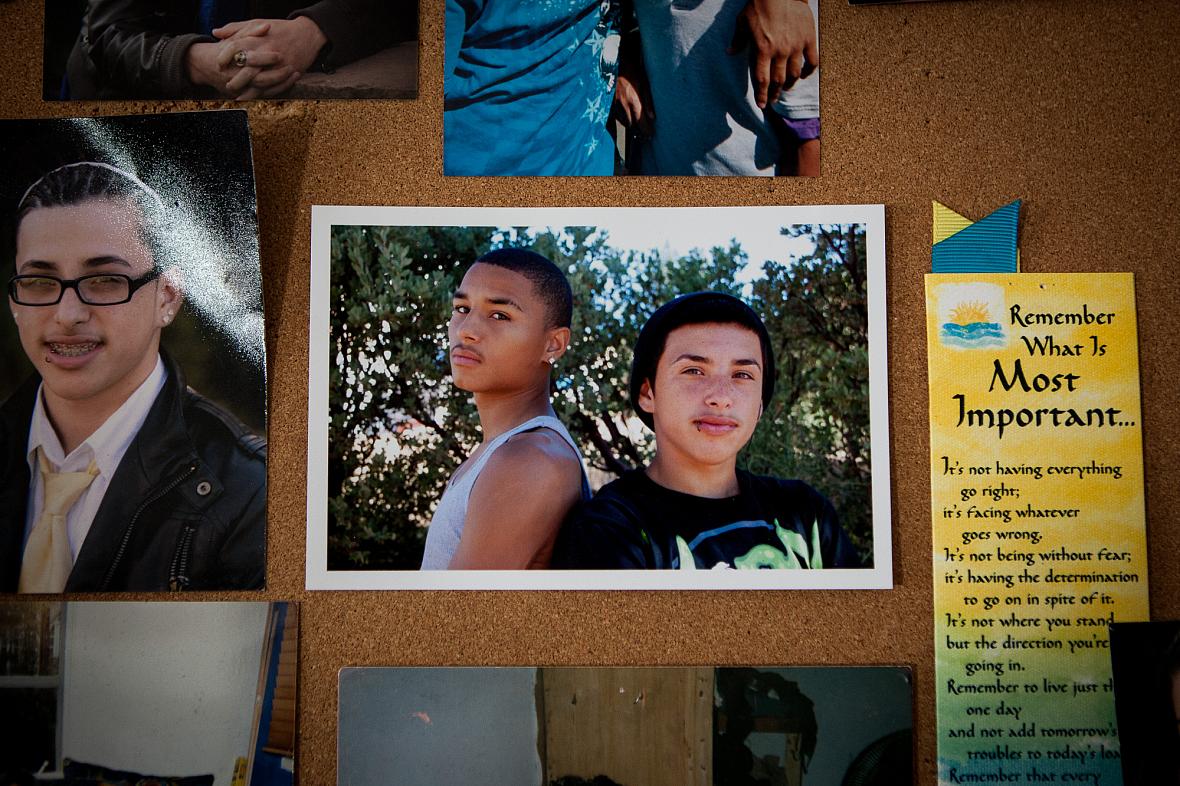

Three brothers, three paths out of foster care

The brothers escaped on a Sunday.

Matt, 14, Terrick, 12, and Joseph, 11 pretended to go to church that day in 2006, but in secret they had planned to run away and never come back. No more living with an angry grandmother who drank. No more beatings with the belt.

They stashed a black plastic garbage bag full of clothes next to a dumpster outside their grandmother’s apartment in Whittier, California, and wore extra socks, shirts and pants underneath their church outfits. Their older sister, 23, would pick them up at a nearby Burger King. From there, according to the brothers, she would whisk them away and raise them as her own.

So instead of stepping onto that church bus as they had done every week past, the Bakhit brothers walked to Burger King praying that whatever lay ahead was better than what they left behind.

Matt, the eldest, was the mastermind. At 14, a wrestler and high school freshman, Matt said living in the strict, abusive home stifled his maturity. How could he grow into a man?

“My grandma, over any little thing, would pull my pants down and whoop me with a belt,” Matt, now 22, said in an interview.

But freedom from his abusive grandmother didn’t mean an end to his and his brothers’ hardships.

Child protection intervened less than a month later at their sister’s San Diego home. The brothers remember a social worker telling them they would not be separated. They packed their belongings once again into plastic bags and piled into the social worker’s car. The brothers cried.

Despite the promise, 20 minutes later the social worker dropped Matt off at a foster home. Terrick and Joseph were taken to the Polinsky Children’s Center, a 24-hour emergency shelter in San Diego for kids without a home, or as Joseph calls it, “purgatory.”

San Diego County’s child welfare department, which oversees foster care and the Polinsky Center, declined to comment on the brothers. The department never discloses information on any children or families who have been under its care, said Child Welfare Services Program Manager Connie Cain.

Having been thrust into foster care, the brothers were forced to navigate an unfamiliar world. Their goal was to stick together. But they were separated, reunited and separated again.

California is home to more than 66,000 foster youth, according to data collected by the California Child Welfare Indicators Project. Nearly all of them have gone through some type of trauma. Two decades of research has shown that children with untreated trauma are more likely to grow up and have health problems. Providing stable homes, with caring adults, and tailoring treatment plans to each child are what these kids need, according to childhood trauma experts.

The tale of the brothers Bakhit exemplifies the strengths and weaknesses of a foster care system struggling to care for thousands of abused and neglected children. The same system that nurtured Joseph also alienated Matt, and lost Terrick to the juvenile justice system, which cut him from foster care and cast him out on the streets: broke, hungry and with nowhere to go.

Terrick pled guilty to stealing a car at age 17 and a judge sent him to a juvenile facility, making him ineligible for foster care benefits, which now extend to age 21 in California.

Once a judge terminates a foster youth’s case, child welfare is basically out of the picture.

“We always comply with the judge’s orders,” Cain said. San Diego County Juvenile Court declined to comment for this story.

Joseph, a success story

Despite a traumatic childhood, Joseph, the youngest, now 19, grew up a success by most standards. He graduated as valedictorian from San Pasqual Academy, a residential school for foster youth. The academy gave him a car: a black 2008 Toyota Scion XD.

When he got accepted to UC Berkeley, scholarships and financial aid available only to foster youth paid his full ride. And because of a 2010 law extending foster care to age 21, he gets a $838 check every month until age 21.

Now in his second year of college, Joseph works at a dorm cafeteria and is engaged to his high school sweetheart.

Falling through the cracks

Terrick and Matt’s experience was totally different.

By the time Joseph graduated from high school, Terrick and Matt were homeless on the streets of downtown San Diego.

Terrick bounced around from group home to group home, rarely staying in one place for more than three months during his five years in foster care. His temper got him in trouble.

Foster care abruptly ended when Terrick took a joy ride in the van his last group home used to cart around boys like himself.

It wasn’t the first time he took the van without permission, but this time he got caught. Three minutes in, police pulled him over on a freeway entrance ramp. The police released him back to the group home only to arrest him the following morning. Terrick pleaded guilty to stealing the car and spent three months in juvenile hall before a judge ordered him to a year at Camp Barrett, a correctional facility for chronic, serious and violent juvenile offenders.

Removing a kid from foster care and placing him or her in a correctional facility isn’t a decision taken lightly, according to Michele Linley, who runs the juvenile division of the San Diego District Attorney’s Office.

Lawyers from all sides, social workers and probation officers meet throughout the process to decide what’s best for the youth.

“There’s always a fine line,” Linley said, speaking generally. “We are concerned about the minor, and what is in the best interest of the minor, but also, we represent the California people and are concerned with public safety.”

The final decision is always up to the judge.

“To punish a youth by taking away his or her foster youth status is not an appropriate use of judicial power,” said State Senator Jim Beall (D-San Jose), who authored Assembly Bill 12, which extends foster care services to the age of 21 from 18 to help the transition into adulthood.

Only active foster youth can take advantage of AB 12. According to Beall, kids who are removed from foster care and sent to the juvenile justice system are, under law, still technically foster youth. They have what are called “waiting placement orders” and can reenter foster care once released from custody.

However, if a judge removes the order and the youth turns 18, he or she can never reenter. Terrick celebrated his 18th birthday at the camp and was released a few weeks later. No longer considered a foster youth, Terrick couldn’t access the money and housing benefits offered to other foster kids his age. He was forever ineligible for the transitional services offered to all other transition-age foster youth, and his younger brother.

“It doesn’t make sense that, by turning 18 without a placement order, a foster youth would be denied AB 12 and could then never ever get it back again,” said Beall. “It is not how AB 12 is supposed to work; in fact, it is the opposite.”

Normally when a foster youth is incarcerated, Beall said, the foster care placement order stays in place. Only a judge can lift the order, and many judges don’t know the rules of AB 12. Beall suggested a legislative fix that would require judges to undergo training in AB 12 extended foster care.

All the people interviewed for this story agree that what happened to Terrick isn’t common.

But no one could confirm that, because that data doesn’t seem to exist. Cain, of child welfare in San Diego, told us they don’t have reliable data on foster youth who end up in jail, cut off from AB 12 benefits. Neither does probation. The Division of Juvenile Justice, which oversees the state facilities that house juvenile offenders, knows it has kids from foster care but doesn’t collect any of that data.

For Terrick, Camp Barrett wasn’t the problem. In fact, it turned out to be a productive year. He got his GED and attended self-help groups, earning a handful of certificates of completion. His troubles began after release.

Without the safety net of the foster care system, Terrick struggled to live in a world for which he wasn’t prepared. He said he survived on the streets by stealing food and smoking methamphetamines, which kept him alert.

When Matt turned 18 in 2010, AB 12 was still a bill waiting for then Governor Schwarzenegger’s signature.

Matt lived in transitional housing for six months while interning at the San Diego District Attorney’s Office. With money to spend and little guidance, Matt partied too hard and management kicked him out.

“I did what someone without a family does,” Matt said. “I spent my money on making friends.”

Mom abandons the boys

Before the brothers ended up with Grandma, they lived with their mother, Michele Bakhit. Michele first smoked crack cocaine at 17, she said in an interview in her San Diego home. That love-hate relationship would last for 28 years.

The boys were with a babysitter the night their mom never came home. Michele was in a motel room, smoking crack cocaine with a friend, she said. Once the the drugs were gone, she needed more. She stole her friend’s van and drove off in the middle of the night to get them.

“I took the car and went to Compton and never came back,” Michele said. “I knew if I came back I’d have to answer for that night.”

She is now 48 years old, and hasn’t smoked crack in a couple years, she said. Wearing rolled-up jeans and a pink tank top, she sat on her bed holding back tears remembering that night. She has the names of her seven children tattooed on her back. All three brothers have different fathers that they’ve never met.

“It was easier for me to not deal with it and not look back and that’s exactly what I did.” Michele spent the next six years in and out of prison for drug-related offenses.

Grandma keeps order with a belt

The three Bakhit brothers went to live with their grandmother, Patricia Ybarra, who admitted to spanking the kids with a belt.

“I just didn’t know how to deal with boys,” Patricia said. “I didn’t know what to do. I’d flip out.”

Patricia’s own mother also ran a strict home with harsh punishments. Now 69, Patricia has made peace with those years. She said she drank a lot back then, but stopped drinking five years ago.

“I don’t regret those years. I can’t. They happened for a reason. What that reason is, I don’t know,” she said. “I just wish that I wasn’t so strict, that I had let them be boys.”

Family reunion

A couple Christmases back, Joseph rounded up his two homeless brothers for a family dinner at Grandma’s house. Their mother was living there too, while she tried to get clean from drugs.

After that Christmas, Michele decided to be a mom. Her goal: to put a roof over Terrick and Matt’s heads. For a while, the three of them stayed in motel rooms. Tensions ran high as the newly reunited family tried to reconnect in a single room with two double beds.

Terrick’s anger escalated. He began punching the walls. His hand would swell up for weeks and, once healed, he’d punch a wall again. It became routine.

“People have always asked me: ‘Why are you so angry?’ I’ve heard that question for years. I told everyone I do not know,” Terrick said. After talking about his anger with Joseph one day, something just clicked. He finally connected his childhood abuse to his anger. “Now, I can tell them it is because of my grandma, because of my past. That is exactly why I was so angry.”

One morning Terrick erupted in anger, fought his brother and punched through a window, which sliced up his arm bad enough to require surgery. It was a moment of clarity for Terrick. He needed to get a grip on his anger.

Getting Over the Pain

Terrick, Matt and their mom now live rent-free together in Spring Valley, a San Diego suburb, where Michele acts as caregiver for a disabled man who provides housing for the family. Joseph lives in Berkeley with his fiancée, while he attends school and works in a dorm cafeteria.

Anger and substance abuse runs in the family, and all except Joseph seem to struggle with it daily. The toll of childhood abuse, addiction and incarceration isn’t easily undone.

The aftereffects linger on, creating a long list of health problems, according to studies by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The research showed that the more abuse, stress and neglect there was during childhood the greater the risk for health problems later in life, including alcoholism, drug use, smoking, depression, suicide, domestic violence, heart disease, liver disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

While Michele said she was off the crack cocaine, she admitted to drinking alcohol. In her purse were a pack of Maverick cigarettes and a miniature bottle of liquor. Not too long ago, Michele was court-ordered to attend anger management classes after getting in a fistfight with a neighbor.

Terrick has mellowed out but still struggles with his anger. He switched from smoking weed everyday to smoking “spice,” a mix of herbs and chemicals found at smoke shops that is sometimes labeled “synthetic marijuana.” But, that too, he hopes to quit someday. His cigarette brand of choice is Newport.

He enrolled at Colorado Technical University and was just hired as a salesman at a mall.

Anger still rages in Matt, who turns to poetry for release. He works in construction and sleeps on the floor of a downstairs apartment at his mother’s workplace, while Terrick and his girlfriend occupy the bedroom.

The brothers’ goal of sticking together never completely panned out. But their bond never broke.

The family speaks proudly of Joseph’s success. He is regarded as the one who made it out.

“I always wished I could be like him,” said Terrick. “I’m not really jealous, but I kind of wish I had the stuff he had.”

On Terrick’s right shoulder are the tattooed initials MTJ: Matt, Terrick, Joseph.