In rural America, maternal health care is vanishing. These moms are most at risk.

This story was published with support from the 2022 Impact Fund for Reporting on Health Equity and Health Systems, a program of USC Annenberg’s Center for Health Journalism.

Other stories in this project include:

Indigenous people are promised health care. For rural moms, it's an empty one.

Inequities in maternal health care access are not new. They have deep roots in history.

Experts: Pregnant people could face greater risk of domestic violence after abortion bans

How to tell the stories of mothers in maternity care deserts

Christine Daniels holds her daughter as she recalls the struggles she had during her pregnancy.

PHOTO ILLUSTRATION; PHOTO BY ALICIA DEVINE/USA TODAY NETWORK

Part 1 of a four-part USA TODAY project examining the lack of maternal health care in America's rural communities of color.

JASPER, Fla. – Five months into her pregnancy, Christine Daniels felt her blood pressure surge. Her head ached, and the skin on her feet stretched and cracked open. Her legs felt so heavy, she could hardly walk to her mom's apartment around the corner.

Help was far away.

In her rural north Florida town, there is no hospital. No emergency room or urgent care center. No maternal health care of any kind. Daniels, 33, had to drive about 70 miles round trip every other week for her prenatal appointments, and to deliver her baby.

“Something's not right," she told medical workers during a clinic visit. "I already had two kids before. My blood pressure’s never been high." She pleaded, Daniels said, but was not prescribed blood pressure medicine.

Her hypertension soared. When she went into labor in spring 2017, she developed life-threatening preeclampsia, a pregnancy complication Black women like her are more likely to suffer.

“You're going to die. Your baby’s going to die,” doctors at the Lake City hospital told her. They explained her uterus was about to rupture and asked: "Miss Daniels. Did they tell you that your baby has fluid in her brain?"

She lay in shock. "No. Nobody told me anything."

Christine Daniels holds her daughter, TeSharria, 5, as she recalls the struggles she had during her pregnancy and childbirth.ALICIA DEVINE/USA TODAY NETWORK

Daniels had an emergency C-section, and her baby survived. But TeSharria, now 5, suffered permanent brain damage. She can’t walk or talk, has seizures and needs five medications a day.

Daniels, who lived in south-central Florida for a few years before returning to the isolated Suwannee River Valley town, can’t help but think that better pregnancy care closer to home would have made a difference.

And not just for her. Her older daughter and sister, who also live in town, suffered dangerous preeclampsia and high-risk pregnancies, too.

"It was the biggest mistake I made, coming back here," Daniels said.

Living in places like Jasper and other maternal health care “deserts” puts people at risk for pregnancy complications and poor outcomes. Research shows this is particularly true if, like Daniels, they are Black.

In rural communities where at least a third of residents are Black, women in Jasper travel among the farthest in the nation for maternal care. The nearest maternity hospital is about 35 miles north across the Georgia border, but USA TODAY reporting found most go about 70 miles south to Gainesville for the specialized care they require.

“I don't want nobody to go through what I had to go through, because it was scary. You feel alone, by yourself. No, it's not a good feeling," Daniels said. "They should do something about it. Build something here for these women.”

About 2 million rural women of childbearing age live in maternity care deserts at least 25 miles away from a labor and delivery unit, a USA TODAY analysis found. Rural hospitals and obstetric wards, already scarce, have continued to shut down in record numbers.

Women of color are even more vulnerable, statistics show, and the federal government has only recently started to identify the problem.

“We have higher-risk women that need more access but actually (are) less likely to get that access," said Tufts University professor Ndidiamaka Amutah-Onukagha, an expert on Black maternal health. Mothers "have to travel further for that access, and have less resources – the perfect storm.”

To understand and illuminate the scope of the problem, USA TODAY visited and interviewed dozens of women and their families, community advocates and leaders, and clinicians and experts, including researchers working with federal officials to map areas lacking care.

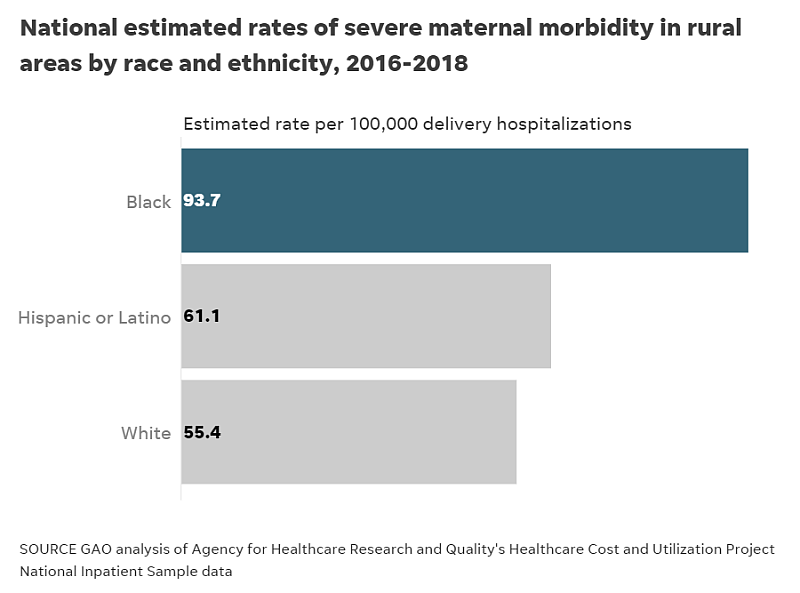

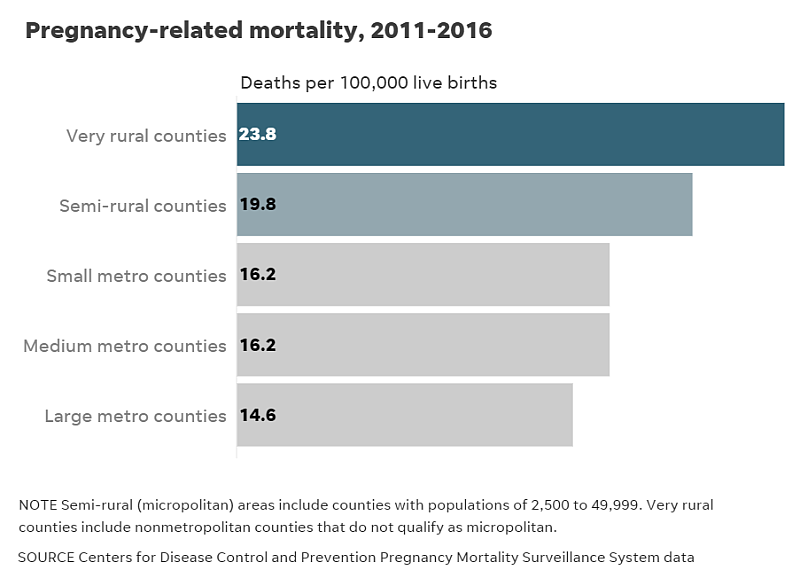

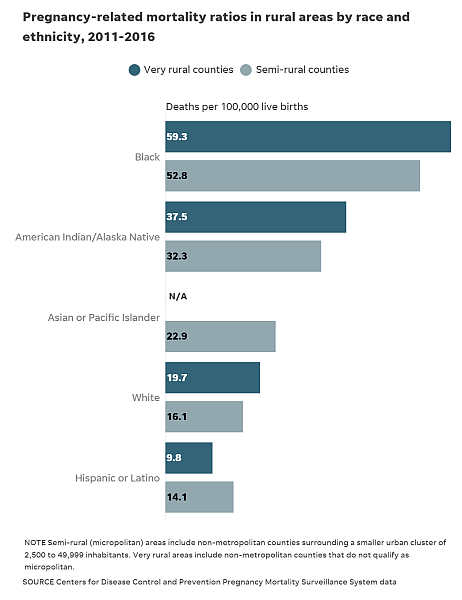

The maternal death rate for rural Black women is three times higher than for rural white women, a 2021 Government Accountability Office report found, and the rate of severe maternal illness for those Black mothers was twice that of white women.

The COVID-19 pandemic made matters worse. The nation’s overall maternal death rate increased and disparities widened. While the death rate for white mothers rose in 2020 from about 18 to 19 deaths per 100,000, Black mothers' death rates remained three times as high, soaring from 44 to 55 deaths. Hispanic mothers' death rates also surged, from 12 to 18 per 100,000, according to the CDC.

At the same time, half of rural hospitals already had no obstetric care, and two dozen hospitals shut down entirely.

"These disparities persist," said neonatologist Dr. Wanda Barfield, director of the CDC's Division of Reproductive Health and a former assistant surgeon general. "This is an issue. And it's an issue that affects those that live in rural communities, and particularly minority women."

In December 2018, Congress passed the Improving Access to Maternity Care Act, directing the Health Resources and Services Administration to identify “maternity care health professional target areas” and distribute health specialists to those places.

Ndidiamaka Amutah-Onukagha is a maternal health care researcher at Tufts University in Boston, Mass. Originally from Trenton, NJ, the hospital where Amutah-Onukagha was born has since closed down. She has dedicated her career to researching maternal health care, specifically for women of color in the U.S. MARY SCHWALM, MARY SCHWALM-USA TODAY

The effort took 18 months to get underway and then was delayed by the pandemic. The agency began just last year to seek general public input on how to define the shortage areas so it could identify them, and finalized criteria in May.

"Everything takes a really long time to move," said Amutah-Onukagha.

The Trump administration, she said, didn't prioritize maternal health but under the Biden administration, there has been renewed attention to the issue.

'A real problem'

The lack of accessible women's reproductive health care doesn’t affect communities equally.

Researcher Peiyin Hung

Half of the nation’s rural counties have no obstetric care or OB-GYN practitioner, and rural Black communities, like Jasper, are more likely to lose their obstetric units, said Katy Kozhimannil, director of the University of Minnesota’s Rural Health Research Center, and Peiyin Hung, deputy director of the University of South Carolina’s Rural and Minority Health Research Center, who have been advising HRSA on the problem.

“Just the population having more Black people made it more likely the counties would lose hospital-based obstetric care,” Kozhimannil said.

Rural communities with larger proportions of people of color are on average farther away from obstetrics than rural white communities, according to research by Hung and others. More than 30% of rural communities of color are at least 30 miles away, compared with 19% of majority-white rural areas. Rural Indigenous communities must travel the farthest to reach care, the research shows.

"If you're in one of these deserts, and you don't have access to transportation, or there's no public transportation, then it's doubly harmful," said Maeve Wallace, a reproductive epidemiologist at Tulane University.

While the distances to maternity care hospitals from white and Black rural communities can be comparable, Hung noted rural Black communities tend to have lower health insurance coverage rates, the lowest median household incomes and lowest access to broadband, which hinders telehealth options. In more than half of majority-Black communities, more than 50% of residents live in poverty.

Lettering for a sign for Hamilton Primary Care peels from the surface. The medical practice has vanished from the shopping plaza. ALICIA DEVINE, USA TODAY NETWORK

Some women, such as those on rural American Indian reservations, must journey more than 100 miles one-way to deliver, according to a USA TODAY analysis of University of South Carolina Rural and Minority Health Research Center research and data from the U.S. Census American Community Survey and American Hospital Association.

“There is a real problem in our rural communities around access to obstetric care. And we know that that is worsened, both in terms of access and outcomes, for moms of color,” said Carrie Cochran-McClain, the National Rural Health Association’s chief policy officer.

Implicit medical bias, unequal distribution of resources and a dearth of consistent, timely prenatal care and obstetrics aggravates existing disparities, experts say.

“It's harder to get the care that you need. It takes longer, it's more dangerous. The resources and infrastructure are not there to support you,” Amutah-Onukagha said. “That's the definition of structural racism – underinvestment in community. You remove the things that improve someone's social determinants of health, and then you leave people to fend for themselves.

"What do you think is going to happen?”

'Got nothing down here'

Pregnant with her third child, Christine Daniels’ daughter Jahirah Daniels, 19, drives about 60 miles round trip to Lake City for prenatal appointments.

Like many mothers in town, Jahirah doesn't have a car. Transport services offered through public insurance are unreliable, she and others said, and sometimes if their children are with them they're denied a ride.

"It takes all day to go to an appointment a lot of times, because they're going to another county," said Julie Moderie, program director of the Healthy Start Coalition, which supports new mothers in need of resources. "Even though there are, what you would think, things in place like that to help, there are still barriers."

To deliver her baby, Jahirah will have to go even farther – a 136-mile round trip drive to Gainesville, a university town where they are sent for the high-risk care.

Jasper's lone primary care clinic shuttered at the beginning of the pandemic in April 2020. Soon after, the hospital where her mother gave birth also shut down, forcing Jahirah to drive an extra hour on country roads to deliver.

NADA HASSANEIN/USA TODAY

"Too far," she said, holding her shy 2-year-old boy on the porch of her apartment before her shift at Love’s convenience store.

"I wish they had a hospital. They don't really got nothing down here. (There aren't) that many support systems down here for pregnant women to go to."

Rural women on average have more babies than urban women. In Jasper, with no abortion services or a full-time primary care doctor, contraception can be expensive and difficult to get. A third of Jasper's Black residents live in poverty.

Half of the town's 4,000 residents are Black, and 1 in 8 are Black women ages 15 to 54. Studded with abandoned brick buildings and surrounded by stretches of peanut farms and plant nurseries, the area also has a significant Hispanic and Latino migrant farmworker community.

A third of Jasper's Black residents live in poverty.

ALICIA DEVINE/USA TODAY NETWORK

Like her mom and aunt, Jahirah's pregnancy is high-risk. She suffered preeclampsia with her first two deliveries and still has hypertension. Several of her neighbors, mothers in the housing project where she lives and in trailers down the street, also had hypertension during their pregnancies, a risk factor for preeclampsia.

Despite her condition, Jahirah said that just like her mom, "they never gave me blood pressure medicine. I don't know why."

On a recent summer morning, her left arm was bruised from an IV after she was hospitalized for bleeding, and found to have a uterine blood clot.

"You'll never understand people's predicament, or what they're going through," she said.

'Very, very fragile'

Over the past three decades, more than 300 rural hospitals have closed, disproportionately in communities of color.

The South, where more than half of the nation’s Black residents live, has lost the most. More than 175 shuttered between 1990 and 2020, according to a University of North Carolina’s Center for Health Services Research report.

Cochran-McClain, the rural health policy expert, said the rural hospital system has been historically underfunded.

“So much of that is because we have typically paid for services in a way that benefits volume in this country,” she said. “A lot of the payment methodologies are just not designed for low-volume providers.”

The federal government has made recent efforts to bolster rural health. In 2020, the Department of Health and Human Services released the Rural Action Plan, its first agency-wide assessment of rural health care in almost two decades. The Biden administration also included more funding in its 2023 budget proposal to expand HRSA's Rural Maternity and Obstetrics Management Strategies program and provide more primary care doctors with training in maternal health.

Obstetrics are known as a “loss leader” in U.S. hospital systems. Among the least lucrative and the most expensive, it’s one of the first services to go, Kozhimannil said. Rural hospitals simply can’t afford to keep them open.

Most rural births are to parents covered by public insurance. The hospitals rely on Medicaid reimbursements, which offer much lower payouts than private insurance companies. Coupled with lower birth volumes compared to urban hospitals, obstetric care is difficult for rural hospitals to maintain.

“The financial incentives in maternity care really work against access in ways that are important,” Kozhimannil said.

During her team's survey, she said, hospital CEOs cold-called her to explain: “'We had to close our obstetric unit. We were so sad, we really wanted to try to keep it,'" she said. "They will operate in the red for a long time before they close.”

In Georgia, more than 55% of the state's counties lack labor and delivery units, according to a legislative report on maternal mortality. None of the state's rural counties have a maternal-fetal medicine specialist.

Dr. Lethenia Joy Baker, an obstetrician and gynecologist in rural Georgia, works at her clinic in LaGrange, Ga. on July 13, 2022. RITA HARPER, FOR USA TODAY

Dr. Lethenia “Joy” Baker has spent most of her career caring for women in rural Georgia. The state has one of the highest Black maternal death rates in the nation.

“It can get really heavy,” Baker said. “We have a serious access problem here.”

That lack of access leads to poor outcomes. Rural hospitals report higher rates of postpartum hemorrhaging and blood transfusions during labor and delivery compared with urban hospitals, a study by Kozhimannil, Hung and colleagues found.

Baker has trained her team to prepare for the worst. She recalled two recent patients who suffered hemorrhages during labor and lost so much blood their entire blood volumes needed to be replaced through transfusions.

She has put in place specific strategies and protocols and is working to create new safety "bundles" through the Alliance for Innovation and Maternal Health for other hospitals to follow.

Compounding the access crisis is a shortage of doctors. Only 10% of OB-GYNs work in rural America. In part because of the loss of providers, the nearest prenatal care for most people in Jasper is from nurse practitioners about 30 miles away.

"Prenatal care providers are a constant rotation," said Moderie, of Healthy Start. "It's challenging. They'll start care with one provider and then that provider leaves. There's no consistency and stability there for them when it comes to care."

Baker, whose practice in LaGrange recently lost three specialists, called the health care "ecosystems" for women outside urban areas, "very, very fragile."

“All it takes is one person to retire, one person can become ill, and then you're fighting an uphill battle,” she said.

Two Hamilton County Emergency Medical Services ambulances sit parked outside the EMS building in Jasper, Florida on Wednesday, July 6, 2022. ALICIA DEVINE, USA TODAY NETWORK

'Equity vs. equality'

Just off the main road in Jasper, a few blocks from the public housing complex where Jahirah Daniels lives, is Hamilton County's Emergency Medical Services.

Paramedics are frequently called to transport moms in labor to a hospital an hour's drive away in Gainesville. Often, EMS chief John Smith said, they have their babies in the ambulance.

Smith acknowledged the county has a maternal health care access crisis.

“I see it as an issue for the whole county,” Smith said. “I don't really see it as a one-ethnic thing. I see it as basically a multi-ethnic problem.”

But over the past decade, Black moms in the county suffered severe maternal illness at nearly twice the rate of white moms, according to Florida Department of Health data.

Such racial disparities aren't biological but are the result of structural neglect, said Tulane's Wallace. Her research found Black women living in Louisiana's maternity care deserts had the highest risk of death during pregnancy and up to a year after giving birth.

“It's not about individual differences. It's about systems and structures that make groups within the population more vulnerable than others,” Wallace said.

Newly elected City Councilwoman Jhelecia Hawkins, 33, has lived in Jasper all her life. A single mom of three, she runs Over the Rainbow, a day care with whimsical, turquoise-painted walls next door to City Hall.

NADA HASSANEIN/USA TODAY

She longs to see the town have a hospital again. Trinity Community Hospital closed more than a decade ago amid allegations of Medicaid fraud.

"It's a necessity," she said. "The drive – that's the struggle. A lot of people here don't have a decent car or vehicle to get them back and forth."

Hawkins, a cervical cancer survivor, had two of her three children in Gainesville, and her own cousin lost a baby. The lack of nearby available care, she said, “touches my heart.”

“We don’t have that access here,” she said. “It definitely can be depressing."

Hawkins said she wishes distribution of health care were focused on "equity versus equality." Rather than treating everyone the same, care should be available and tailored to meet individual needs.

“If we could be more about equity,” she said, “a lot of things would be better off.”

Shakela 'Tootie' Jones, 37, struggled with her last two pregnancies and suffered from preeclampsia. ALICIA DEVINE, USA TODAY NETWORK

'Poor little Jasper'

On a sweltering summer afternoon, Shakela Jones' mobile home buzzed with activity.

Five-year-old Marqualin, wearing a butterfly shirt and glittering tutu, peered into an aquarium holding the family's pet bearded dragon while cradling a tiny calico kitten.

In the kitchen, Jakeila, 9, stirred grits on the stove while Jones sat on the black leather sectional with her 2-year-old, Nathaniel, dressed in a Spiderman costume, cooling off in the breeze of a box fan.

Like many other women in town, Jones said Jasper needs a facility to support high-risk moms like her, her sister Christine Daniels and niece Jahirah.

“It’s not safe at all,” she said.

Each of Jones' five children was born at a hospital at least 30 miles away. After her first C-section, she said, “I just had problems with every last one of my pregnancies.”

Her second-oldest, Vicqualin, now 16, was born premature at 2 pounds. With two of her high-risk pregnancies Jones suffered preeclampsia. “It was stroke level," she said. "My blood pressure wasn't supposed to be as high as it was at the time."

Jones feels her community, where flyers for cheap funeral caskets and high-speed internet are posted along quiet streets, has been forgotten. "Like it’s ‘Poor little Jasper,' like they don’t care about it.”

Jakeila, 9, and her little brother Nathaniel, 2, peek their heads out the door of their home in Jasper, Florida Wednesday, July 6, 2022. ALICIA DEVINE, USA TODAY NETWORK

What improvements are made, like the freshly painted white post office and the newly paved driveway of a commercial fuel station, don't make her life better. She was disappointed when she recently learned the town's physician assistant's clinic was getting a new building.

"They shouldn't do that. They should just build a whole 'nother hospital," Jones said. "Everybody has to get life-flighted out or have to be in a rush to go to Lake City or Gainesville when it should be a hospital right here in town."

It seems richer city mothers matter more – as if "we don't deserve the same treatment as theirs."

It's not fair, she said.

"We deserve it. But we don't get it."

This project was produced for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 Impact Fund for Reporting on Health Equity and Health Systems. USA TODAY's Nada Hassanein, environmental and health inequities national correspondent, spent months reporting on the issue, interviewing more than 50 experts, mothers, clinicians, advocates and community leaders. Senior data reporter Doug Caruso contributed to this report, and graphics journalists Janie Haseman and Jennifer Borresen illustrated the project.

Reach Nada Hassanein at nhassanein@usatoday.com or on Twitter @nhassanein_.

[This article was originally published by USA Today.]

Did you like this story? Your support means a lot! Your tax-deductible donation will advance our mission of supporting journalism as a catalyst for change.