Pregnant Behind Bars, Part 4: The Mothers

This series by WitnessLA’s assistant editor, Taylor Walker, was produced as project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2021 California Fellowship.

Her other work includes:

Pregnant Behind Bars, Part One: Second Chances

Pregnant Behind Bars, Part Two: When Housing Changes Everything

Pregnant Behind Bars, Part 3: When Things Go Wrong During Diversion

Pregnant Behind Bars, Part Five: Looking To The Future

New Report Urges LASD To Release More Pregnant People From Jail, Improve Conditions

WitnessLA

This is the fourth part of WitnessLA’s five-part series about Los Angeles County’s special Maternal Health Diversion Program aimed at keeping justice system-involved pregnant people in supportive housing and out of jail.

Previously in this series, we’ve shown you how the diversion program, which has had at least 200 participants, works from start to finish.

Yet the best way to understand why programs like this one are so important, is to hear from the mothers themselves.

In Part 4, the moms talk about what it’s like to be pregnant in jail, and about their lives before and after incarceration.

A close call

When, in the first few days of 2019, the results of Leslie Garcia’s jail intake health screening arrived, they contained surprising information. Garcia was pregnant.

Two months later, Los Angeles County’s Office of Diversion and Reentry convinced a Torrance judge to approve the transfer of Garcia’s case to a diversion courtroom in downtown LA. Garcia was released into the Maternal Health Diversion Program’s interim housing soon after, and she gave birth to a healthy baby named Armanee.

Before she was approved and transferred, however, Garcia said she nearly miscarried while locked inside LA County’s main women’s jail, the Century Regional Detention Facility (CRDF), located in Lynwood, CA.

Garcia was 14 weeks into her pregnancy when, all at once, she discovered that she was bleeding heavily. Garcia pounded on her cell door, and shouted for help. “I was losing her, and banging for a medical emergency,” she said.

Garcia sat scared and “soaking in blood,” for what she believed was eight hours, waiting for jail staff to coordinate her transfer to the hospital.

That’s not how it’s supposed to be, said former Assistant Sheriff in charge of the LA County Sheriff’s Department’s Custody Division, Robert Olmsted, “but it wouldn’t surprise me.”

In the meantime, Garcia said, she bled through multiple clean pairs of pants deputies gave her.

When emergency responders appeared to transport her, Garcia said she heard them complain to LASD staff that it took them an hour to get inside the jail after they arrived.

Once Garcia arrived at nearby St. Francis Medical Center, the news from the physicians was initially distressing. “When I get to the hospital, [doctors] tell me she’s almost dead,” she said, referring to her now two-year-old daughter, Armanee.

The threat of misscarriage made Garcia feel desperate to hold on to her baby.

Thankfully, Garcia said, the doctors acted quickly and were able to stabilize her pregnancy.

Two months later, when Garcia was five months pregnant, Maternal Health Diversion Program facilitators secured her release from jail, and brought her to live at one of the program’s community-based group homes — a temporary placement until participants are ready to move into their own apartments.

Garcia’s daughter, Armanee, is now a healthy toddler who reportedly loves to dance and play with her older brother, Cole, a first-grader.

Although Garcia has technically completed probation and graduated from the MHD Program, she will be able to continue to live with her young children in permanent supportive housing for as long as she needs it.

Leslie Garcias children, Armanee and Cole. Courtesy of Leslie Garcia.

The long path to a stable life

Garcia was in her 30s before the kind of help and support offered by the pregnancy diversion program entered her life. That aspect of her story is not unique. Most of the mothers I spoke with said they wished assistance had come sooner, before they found themselves in jail or prison, and before they lost their kids.

Long before the point of lock-up, the moms said they experienced problems for which they might have gotten assistance — things like housing insecurity and homelessness, domestic violence, substance use disorder, and involvement with the child welfare system.

During my visits with Garcia and others in the program, we’d talk while the moms moved around their homes.

They cooked meals and fed their kids, played with them, and soothed away fussiness while telling stories of their own childhoods, about what it was like to be pregnant in jail, and about life with their children on the other side of instability and incarceration.

The kindness of the Maternal Health Diversion Program women, despite the challenges they faced, stood out to Chapawnie Forbes, a former case manager with Project 180, one of the community-based organizations partnering on the program.

We negatively stereotype people coming out of jail, said Forbes, “but the majority of the clients that I’ve had … are so nice.”

“A lot of them end up in jail because of trauma they’ve experienced,” said Forbes.

Go to jail, lose everything

Leslie Garcia’s childhood was thrown into chaos, she said, when her own mother died. There was no other family to take care of the then 12-year-old, so she was shuttled into the foster care system..

“Some people are raised, and some people just grow up. I grew up,” Garcia told me, as she sat with two-year-old Armanee at their kitchen table.

By the time she was 18, Garcia was on a path that alternated between incarceration and homelessness

While Garcia has been incarcerated for more serious crimes, many of her arrests were for crimes tied to survival, like shoplifting, she said.

“People think, well, you live the life you choose,” Garcia said. But you’re left with little choice when you “come out of jail and you have no clothes,” she said. “Obviously I have to go out and get some.”

Like Garcia, most of the mothers with whom I spoke said they had experienced homelessness.

Several women told stories of being physically and/or sexually abused as children, and of domestic violence from past partners.

After her father sexually abused her as a child, Michelle Loest said that she struggled with substance use disorder as an adult, and faced severe physical abuse from a series of partners.

Bernadette Campos with her daughter, Jezabelle. Courtesy of Bernadette Campos.

Now, with the support of the Maternal Health Diversion Program, permanent housing, and a caring husband who got sober with her after she became pregnant with Emma, her second child, Loest and her little family have spent two happy, stable years together. “I’m blessed,” Loest said of her new life.

Like Loest, most MHD mothers with substance use problems said they used drugs in response to traumatic experiences.

In a survey of women in jail cited in a 2019 report from the Vera Institute of Justice, 86 percent of respondents said they had experienced sexual victimization in their lifetime, 77 percent reported experiencing intimate partner violence, and 60 percent said they were abused by their parents or caregivers.

The report authors pointed to another survey in which 82 percent of 500 jailed women said that they had experienced drug or alcohol abuse or dependence in their lifetime.

Jailed women also reported serious mental illness at rates more than six times higher than women in the general public, research in the Vera report shows. And jailed women are far more likely than women in the general population — and often more likely than men in jail — to have experienced adversities like chronic health conditions, homelessness, unemployment and underemployment.

Further adversity and trauma often awaits the women in jail, a setting mothers described as horrible, stressful, and dehumanizing, a situation that becomes more pronounced for those who are pregnant.

Giving birth while in custody

Bernadette Campos said that in her jail pod, she watched deputies make a woman who was pregnant with twins wait for what felt like an unnecessarily long time for hospital care. The woman’s water had just broken, and according to Campos, deputies made the woman stay on her bunk, telling her she had to wait until she was actually in labor to go to the hospital.

To Campos, it seemed clear that the woman was likely already in labor. “She was grabbing her belly. She was screaming,” Campos said.

Giving birth while incarcerated is an incredibly distressing experience even when there are no complications, said another mother, Monique Rosales.

Photo of Monique Rosales courtesy of Monique Rosales.

About a year before Rosales entered the Maternal Health Diversion Program, she was nearing the end of a previous pregnancy, and was locked in a prison in Nevada.

At the hospital, guards, rather than loved ones, were present for her baby’s birth. “They’re so cold, the guards that are right there watching you,” she said.

“Going through that alone, it’s hard,” said Rosales. “And then having to have your baby and leave him there to go back to prison … it’s horrible.”

An aunt and uncle who lived in Nevada were able to pick Rosales’s newborn from the hospital. Without them, she said, “the baby would have been in the [foster care] system in Nevada, away from my family, away from my home.”

Monique Rosales and Leslie Garcia were both fortunate in that they had loved ones willing to step in and care for their kids. Bernadette Campos, too, had a father who was able to raise her first, now-adult daughter while she was in and out of prisons and jails.

Separated and sent into foster care

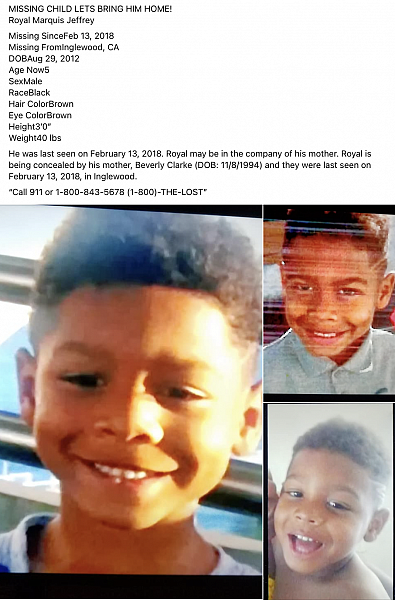

For Beverly Clarke, a brief incarceration on an old warrant sent her son, Royal, into the foster care system for eight months, a period that Clarke described as deeply traumatizing for both mother and son.

That period of separation began one night in 2017, when Clarke’s new boyfriend called her to come pick him up in an area unfamiliar to her. When Clarke arrived, she found her boyfriend “was doing stuff he didn’t have business doing.”

When the police showed up, then-22-year-old Clarke said she was shocked when officers said that she, too, would be arrested on a four-year-old warrant.

Before her 2017 arrest, Clarke said she was employed, renting an apartment, and her six-year-old son was enrolled in school.

When she was arrested, Clarke’s son Royal was placed in foster care. Her incarceration was brief, but Royal was not allowed to come back home to his mother when she got out. Clarke became severely depressed in response.

Her DCFS social worker, Clarke said, made the experience far worse. Rather than motivating her and helping her along the path to family reunification, according to Clarke, the social worker “made it seem like nothing I did was good … “like I was never going to get my son back.”

Despite having no history of substance use, “I started using pills,” Clarke said, “Xanax and stuff like that. I just wasn’t in my right state of mind. They took my son.”

Royal, who was in foster care for a total of eight months, had been transferred into the care of one of the administrators at the boy’s school, Clarke said. One day, when Clarke went to visit her son, she said Royal began crying and told her one of the foster parent’s own children was touching him inappropriately.

Clarke said she had no faith that her social worker would protect Royal. She called her boyfriend to pick up both mother and son from the visit. “I’m not leaving my baby,” she told him, “I’m not leaving him here.”

Legally speaking, Clarke kidnapped her son from the foster care system.

She and Royal hid in Los Angeles for a month before traveling to her mother’s house in Texas. Meanwhile, police were actively searching for them, canvassing areas they thought she might be with photos of Clarke and her son.

Photos of Royal were even on Facebook, with a call for neighbors to be on the lookout.

Photos of Beverly Clarkes son, Royal Jeffrey, from Facebook.

Two months into her time in Texas, police found Clarke, arrested her, and flew her son back to Los Angeles. Ten days later LA police flew Clarke home and sent her into CRDF — LA’s women’s jail.

That’s when Clarke found out she was pregnant for a second time. That positive pregnancy test in jail, in 2018, it turned out, was a ticket into housing, services, and reunification with Royal. Clarke’s felony kidnapping charge was also dropped to a misdemeanor.

Clarke, now 26 years old, has graduated from the Maternal Health Diversion Program, and is no longer on probation. She lives with mother, her boyfriend, her three children, and their bulldog named after the deceased rapper, Pop Smoke, in a white craftsman-style home on a quiet street in El Monte.

“If I didn’t get into the program,” Clarke said, tears running down her face, “I don’t know what I would be doing.”

Instability before incarceration

Before her initial incarceration, Beverly Clarke struggled financially. She was working, but not always able to afford rent, utilities, or a car. “It wasn’t like I was out here just recklessly living,” she said. “I wasn’t stable with housing,” Clarke said. “I was staying from place to place. I would get an apartment and lose the apartment.”

It didn’t help that the foster care and incarceration odds were not in Beverly and Royal’s favor.

Black women are locked up at rates disproportionate to their portion of the general population in LA County, and across the country.

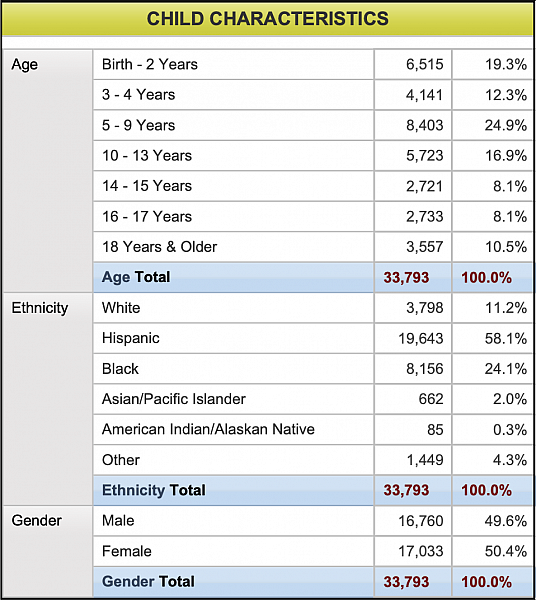

Black children comprise nearly 25 percent of kids (8,156 kids) in LA’s foster care system, yet make up approximately 7.5 percent of kids in LA County. By comparison, white children account for 20.4 percent of LA’s youth and just 11 percent of kids in the child welfare system.

Research suggests that 58% of Black children in LA will endure a DCFS investigation before the age of 18.

Beverly Clarke says she believes those particular struggles are behind her, thanks in large part to the Maternal Health Program’s intervention. “I really thought I wasn’t going to get my son back, and now I have two more babies,” she said.

“I’m happy. I have a house and I’m 26,” she said. “I don’t think it can get no better than that.”

Chart via Los Angeles County Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS).

Volunteering for diversion

Monique Rosales, the mother who gave birth in a Nevada prison, nearly missed out on the diversion program, when her charges were suddenly dropped.

Rosales was pregnant with another child in LA’s women’s jail for about a month for a drug-related offense. During that time, Rosales stayed sober, and had accepted help from the diversion program. While she was waiting for her case to be transferred to the diversion court, her charges were dropped unexpectedly, and she was released from jail.

“I was at a motel for the night. I didn’t really know where I was going to go,” she said. “I didn’t really have a place to stay at that point. I didn’t know what to do.”

Monique was worried she wouldn’t be able to manage sobriety without help.

She didn’t want her baby, who had already lived in the custody of Rosales’s aunt and uncle, to go through the repeated upheaval his older siblings had experienced. She also wanted to have a healthy pregnancy, the likelihood of which was rapidly receding, the longer she stayed in the motel with her son’s father, who was using drugs.

So, when her boyfriend left for work, she called Aubree Lovelace, MHD’s then-director. Rosales asked if she could still participate in the program, despite no longer being held in jail.

Lovelace called back the same day, and said that if Monique was serious about participating, they would have someone come get her right then and there. “Chapawnie [Forbes] picked me up and took me to the interim housing,” Monique said. “After that, everything changed.”

Living in interim housing, with structured classes and visits from case managers and therapists, in a clean and healthy environment, Rosales said, “gave me a peace I think I needed, and I stayed sober.”

While she had her baby with her during the six months she was in MHD housing, Rosales’s older children remained with their grandmother. Once she moved into her own permanent housing, she reunited with her kids.

“I have them all with me now,” she said. While it would have been wildly difficult to reach this outcome without the program, Rosales said she had to be ready to do the work necessary. “I had hit rock bottom way too many times,” she said. “I was ready. I volunteered to do this,” she said.

“I was like, ‘I’ll take the house. You’re willing to offer it to me, I’ll take it.’”

But pregnant people shouldn’t be the sole group eligible for the program, according to Rosales.

Instead, the program should be expanded to reach mothers in general. Helping incarcerated mothers whose kids might be lost to the system “would make a big difference,” she said. The system should work to keep families together, “instead of separating parents from their children,” she said.

“They’re quick to do that.”

This series by WitnessLA’s assistant editor, Taylor Walker, was produced as project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2021 California Fellowship.

Featured image: Leslie Garcia and her children. Courtesy of Leslie Garcia.

[This article was originally published by WitnessLA.]