A new diversion program for LA’s incarcerated pregnant people looks promising, despite scant data

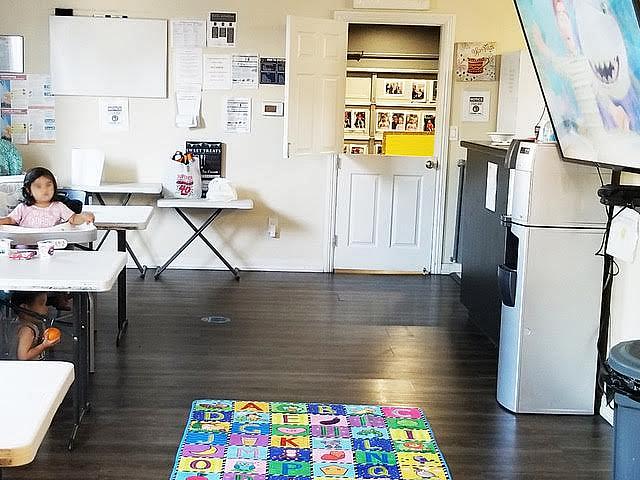

A dining area inside the Maternal Health Diversion Program’s interim housing.

(Image via WitnessLA)

In April 2020, I read a brief report on Los Angeles County’s efforts to reduce incarceration among vulnerable groups — including people with mental health diagnoses and unhoused individuals — through diversion programs.

I was particularly interested in a relatively new program focused on getting pregnant people out of jail and into housing where they would be supported during and after their pregnancy with an array of services. This program is unique to Los Angeles County, in that it provides supportive housing for life — or for as long as participants need the help.

The report from LA’s Office of Diversion and Reentry (ODR) revealed that, as of March 2020, the Maternal Health Diversion Program had removed 137 pregnant people from the county’s main women’s jail since the program’s 2018 inception. Most participants, the report said, were in interim housing, where they could live during and after pregnancy, and where children from whom they were separated due to incarceration could live too. Forty people had graduated from interim housing into their own apartments and houses.

At the outset, I wanted to know more about the maternal health program and about the participants. Yet my early searches turned up little additional information.

What I did find, then and during the course of deeper reporting for my ongoing series about diverting pregnant people from LA’s jails, was that data was hard to come by. But a lack of data can also be an important part of the story.

I knew that incarceration separated an incredible number of families each year, and that women’s incarceration rates had exploded since the late 1970s. Now, approximately 80% of the 2.9 million women jailed each year in the U.S. are mothers, and most are their children’s primary caregivers. At the local level, a 2019 report by UCLA’s Million Dollar Hoods Project revealed that between 2010 and 2016, the LA County Sheriff’s Department booked 173,000 women into jail at a cost of $752 million — figures that don’t capture the incredible personal toll on mothers and children, as well as their families and communities.

While LA County has pushed in recent years to improve and expand data collection, there are still gaping holes in what we know about county systems and programs, as well as the people who are impacted by those systems.

I found there were no comprehensive statistics about demographics of those in the MHD program. Until September 2021, the most useful data existed within a January 2020 RAND Corporation study encompassing the entire population — 311 people — enrolled in ODR’s supportive housing between April 2016 and April 2019. Those in maternal health housing comprised a small percentage of that total.

(Still, the study offered general demographics and showed promising data around outcomes.

Ninety-one percent had stable housing after six months in the program, 74% had stable housing after a year, and 86% remained free of new felony convictions after a year.)

Then, in September 2021, as I was writing the second part of the series, Dr. Kristen Ochoa, ODR’s medical director, sent me information that was more specific to the Maternal Health Program.

It was a screenshot of a chart from an LA County CEO report still in the works that offered information on 15% of the women in the county’s maternal diversion program.

Despite the small sample size, it was helpful to know that 21% of the women were identified as chronically homeless, and 43% were reported to have a serious mental health diagnosis. The chart also confirmed racial disparities in justice system involvement for women of color, and gave information on the percentage of people entering the program with felony charges versus misdemeanors.

I tried to work around the issue of incomplete demographic data by calling, emailing, and submitting a Public Records Act request to the LA County Sheriff’s Department seeking data on the pregnant people held in the Century Regional Detention Facility. The sheriff’s department is notoriously bad about responding to Public Records Act requests, and this line of inquiry failed.

While I was able to finagle some useable data into my series, the lack of data became an important part of the story, and one that helped to frame the most important part — the mothers’ stories.

The Office of Diversion and Reentry was very accommodating with this portion of my reporting process. Case managers asked their clients whether they would be comfortable talking with a reporter, and compiled a list of names and phone numbers for me. I also asked some of the women who agreed to interviews whether they knew anyone else who might want to talk about their experiences.

At the beginning, I asked mothers if they would be comfortable with the interviews being recorded or videotaped, so that they could tell their own stories, in their own voices. Some were happy to be recorded, others told me they were uncomfortable with the idea. The mix of media types turned out just fine.

I was also worried that interviewing the mothers who agreed to share their stories with me might dredge up traumatic experiences.

And women did share stories of living unhoused, of past domestic violence, of sex trafficking, and of terrible things that happened to them in jail. I handled their stories with care, and left space for the mothers to withdraw parts of their stories they were uncomfortable having published on the internet.

One mother agreed to an in-person interview, but called back hours later to say that she was feeling distressed by the idea of rehashing her old traumas. She had already processed those events in therapy, she said, and she was finally happy and doing well. This mother shared her thoughts about the diversion program and about the all-too-common cycle between homelessness and incarceration, but she also wanted to leave the details of her past — which included enduring several pregnancies while unhoused — behind.

Yet I was surprised by the fact that most mothers I contacted were eager to tell me about their experiences. One mother said the interview process was therapeutic. Another said she was shocked that anyone would even care to listen to her story. They all said they hoped sharing might help other pregnant women and mothers in similar circumstances feel less alone.