'Mom needs help. I'm going to work.' The pandemic's toll on the education of Florida's migrant students

This story was produced by Janine Zeitlin, a participant in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism's 2020 Data Fellowship.

Her other stories include:

What is Florida’s plan for vaccinating thousands of farmworkers? It’s unclear

Nikki Fried to Gov. DeSantis: Give Florida farmworkers, all teachers COVID-19 vaccines now

How Florida left farmworkers out of its COVID-19 pandemic response

Florida farmworkers struggled to get vaccinated. But health officials finding ways to help

We had to work twice as hard': How the pandemic magnified inequities for Florida's migrant students

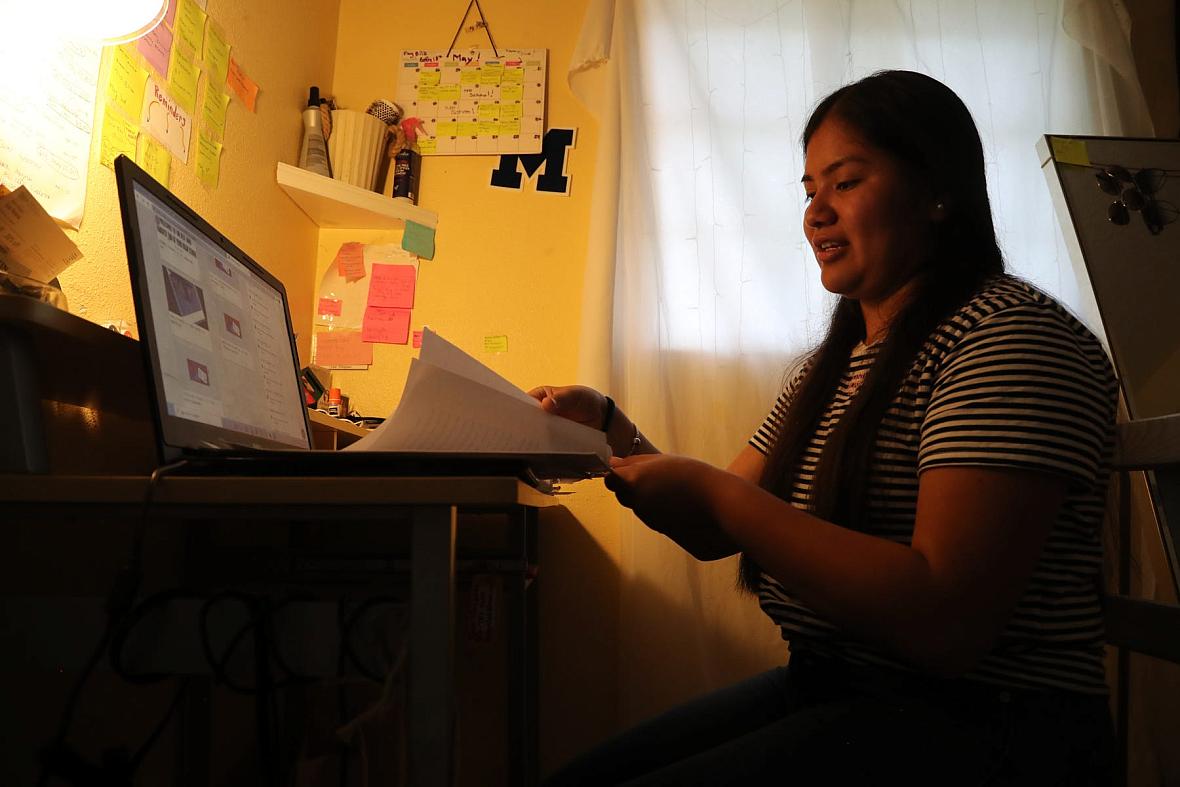

Luz Vazquez Hernandez talks about the papers she wrote for scholarships for college. Vazquez, 18, is the daughter of farmworkers who migrate between Florida and Michigan. Shortly after her 14th birthday, she began working in the fields with her parents. Last year during the pandemic, she picked crops during the day and did her homework at night. "I just made it work."

ANDREA MELENDEZ/THE USA TODAY NETWORK-FLORIDA

During the pandemic, farmworker parents struggled with basic bills like rent and water. Many are still catching up. Migrant mothers stopped working to care for children. Students juggled virtual school with work, sometimes alongside their parents in fields. Some fell behind as they fought spotty internet connections.

But when migrant students did go back to the classroom, sometimes months after schools opened, parents often saw dramatic improvements, allaying some fears their children will be left behind.

The USA TODAY Network-Florida spoke with migrant students and parents across the state as part of a monthslong effort to highlight the vulnerabilities Florida farmworkers and their children have faced during the pandemic.

Here are some of their stories, in their own words. (Interviews were lightly edited for space and clarity and in some cases conducted in Spanish.)

Luz Vazquez Hernandez, 18

My parents are both farmworkers. Here in Florida, they pick strawberries, and later squash. Last year was our first time staying in Florida for the summer because of the pandemic. They didn’t want to risk it.

Usually when we go up north, in Michigan, my parents, brother and I would go to pick blueberries. My birthday is in the summer. When I turned 14, that day, that morning, my mom took me to the office and we filled out the paperwork. They told us, "She can start tomorrow." The next morning, I woke up with my brother, my dad, my mom. I was excited. But from there on, it was just repetitive.

Here in Florida, I do work weekends or days off with my parents. (Florida allows children to work in agriculture at age 14 outside school hours.)

Calabaza crece en un campo alrededor de Dover en el condado de Hillsborough, Florida. Es el hogar de muchas familias migrantes. Andrea Melendez/The USA TODAY Network-Florida

Once school closed, I went with my mom while I did online learning. My mom needed transportation. Dropping her off, I felt bad, and it was a waste of gas if I went back and forth. I told my older brother: "I think Mom needs help. I’m going to start working with her."

My mom would wake me up at 6, 6:30. She would make lunch, and I would start loading everything into the truck. It was the ending of strawberry season.

During work, sometimes my teacher might do a Zoom meeting and I would tell them, "Oh, I’m occupied" and would send my teacher a message. They told me as long as I turn in my stuff on time I would be good. I would always write anything I remembered during work in my notes in my phone.

I would typically get home around 4 to 5. Sometimes I would sleep and didn’t notice the time and it was like 7. I did schoolwork from around 8 to midnight or until I was done. I was taking three AP classes. I managed to turn everything in on time and still wake up early. It was quite tiring.

That lasted until June. My dad had started going into roofing. I knew my dad wouldn’t make enough if he worked by himself, so I started going. My mom was afraid of heights, so I didn’t want to risk her going up there. That was the first year I did roofing, pulling off shingles. It was really intense. The heat was just not the same as out in the fields. I lasted longer sometimes than my dad.

We used to live nearby in Dover, Florida, us and another family in a trailer. It was just one room we all shared. Me and my older brother shared a twin bed. The younger ones would sleep with my parents, so four in a bed. I was always against the wall, like really squished. Once my older brother got older, he started sleeping on the couch.

Luz Vazquez Hernandez in her room in Mulberry, Florida. This is where she spent most of her time working on homework during the pandemic. She was taking three AP classes during virtual school, which she balanced with working during the school day in the fields. This spring she graduated with a 3.9 GPA. ANDREA MELENDEZ/THE USA TODAY NETWORK-FLORIDA

Me and my older brother, we just hope that my younger ones don’t have to go out there and do the same things that we have to do. Sometimes we have taken them. My parents see it as a life lesson, just to see what they’re doing and how money is earned. To see the pain and work.

Coming from a migrant culture, we know what hard work is. Many people do not. I’ve been told I’m a hard worker, and I do believe that too.

I was accepted to Michigan State University. My brother will be a senior there. He hopes to get a good job and give back to my parents. He’s been getting internships, and I hope I get that too, so I can have an indoor job.

I do feel like I missed out on things, but I know for many other older children in the migrant culture, it’s a normal thing that they have to go to work. Sometimes my brother and I, we’d go through social media: "Oh look, our friends are at the beach or having parties" and we’re just like working all day, but we just kind of laugh about it.

Everyone in my family is really close, so we do have moments in the field, we tell each other, "Right now, we could be in a pool or something." We just tell each other, "One day, we’ll become something in life."

Luz Vazquez Hernandez, 18, graduated from Mulberry Senior High in May. Her family typically migrates to Michigan to pick blueberries.

Matilde Angeles, 51

Virtual school was very hard for me. I’m not very familiar with technology or the computer. How could I teach my son if I didn’t know what to do myself?

But in virtual school, my son had more time. He spent more time with his books. In spite of being left alone all day – because everyone else in the house leaves to go to work – he focused on studying. He wants to get good grades so in the future he can receive scholarships.

(His grades rose from a B to an A average during virtual school.)

Matilde Angeles, 51, is a Naples resident and mother to a 16-year-old son. She migrates during the summers for tomato work.

Jesus Hernandez, 44

Jesus Hernandez and his wife, Julia, both farmworkers in the Plant City area, with their daughters Zaira, 4, Yaretzi, 7, Yareli, 7, and Yulisa, 5. Right, Yulisa and Zaira Hernandez in preschool at Redlands Christian Migrant Association center in Dover, Florida. The organization provides bilingual education. At the preschool, teachers use English and Spanish to bolster language skills. The girls now speak English too. ANDREA MELENDEZ/THE NEWS-PRESS/USA TODAY,FLORIDA NETWORK

When this started, we didn’t have enough work. There weren’t buyers for the harvest we were working, picking squash. We didn’t have enough money for rent, food, the electricity. It varies, but typically my wife and I, we can each earn about $400 a week.

What worries me the most now is that my 7-year-old daughters are a little behind in school. The teacher says they’re doing fine in math and other subjects, but they can’t read.

Because I can’t speak or read English, I couldn’t teach them that when school closed.

Sometimes I think, "I’ve lived here 19 years and I’ve always worked only with Hispanic people." With my co-workers, we always speak Spanish. Because of that, I didn’t think it was very important for me to speak English until this happened.

During the struggles with homework, I thought, why didn’t I study English? If I had studied a little English, maybe I could have taught them more words. And now I feel guilty, that it’s my fault that because I didn’t get help to learn English, that it’s my fault they’re behind.

Jesus Hernandez, 44, of Plant City is the father of four daughters: 7-year-old twins and 4- and 5-year-old preschoolers. The family migrates to Ohio for the summers.

Brandon Garcia, 13

Brandon Garcia, 13, found virtual school to be tough. His grades slipped and some days he climbed an apple tree to connect to school because the internet connection was better. ANDREA MELENDEZ/THE USA TODAY NETWORK-FLORIDA

Virtual school was very tough. The Wi-Fi went in and out, in and out. I tried logging in, and the password wouldn’t work. I was kind of late to the classes because of the internetconnection. I tried my best, but it didn’t go really well. I had a tablet. That was also very challenging. Sometimes you need like, an actual computer. It wasn’t programmed by the school to have all the things you need.

I’m doing better face to face. My grades have gone up. I have some C’s and B’s. I’ve made more friends. Not just that, I’m trying to be more of a better person, trying to be more focused on school. I get easily distracted talking to other kids. I try not to, but their topics are so interesting.

Brandon Garcia, 13, lives in Plant City. His family migrates to Michigan for the summer.

Claudia Landeros, 32

My husband and I both pick cherry tomatoes. I had to stop working to devote my time to the girls and to try to help them with their schoolwork.

In the beginning, the girls liked the virtual school because they didn’t have to go to school, but when we started this school year, it was completely different. They didn’t like it and their grades dropped, for both of them, but more for my daughter in third grade. She had been on honor roll and her grades dropped to F’s and D’s.

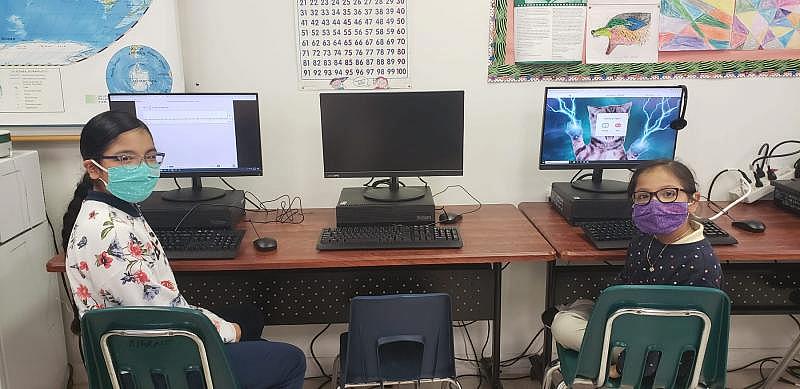

The daughters of Florida City migrant worker Claudia Landeros returned to in-person school in Florida City because their grades were dropping while they were in virtual school, Landeros said. MIAMI-DADE PUBLIC SCHOOLS MIGRANT PROGRAM

Since about March, the girls returned to school, face to face. With every precaution I could take and with the fear of the world on my shoulders, I sent them because they needed to go. I didn’t want them to get left behind.

I told them, "I don’t care if other kids look at you like you’re crazy, clean everything that you’re going to touch." The worry will be there until this virus goes away.

Their grades have gone up significantly.

This year, they’re doing testing, and the stress of testing doesn’t seem fair to me given the stress of everything that’s happened.

They ask me, "Mami, what if I don’t do well?" I tell them: "Try your best. If you fail or you don’t fail, we’ll focus on next year and keep moving forward."

Claudia Landeros, 32, of Florida City, is the mother of four daughters: 11, 8, and 4-year-old twins. The family typically migrates to South Carolina for summer work.

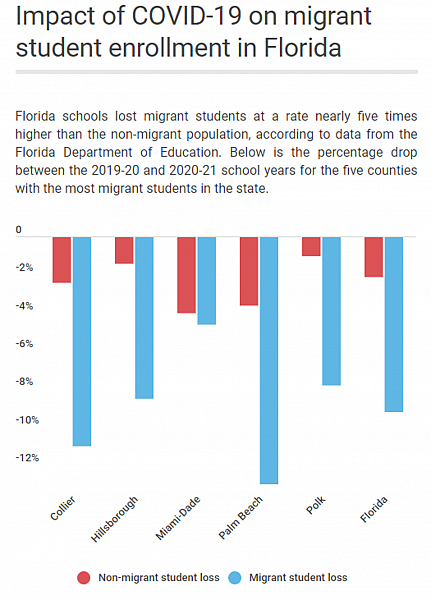

Up next: A deeper look at the data

How COVID-19 magnified inequities for Florida's migrant students, coming June 30.

Janine Zeitlin is an enterprise reporter in Southwest Florida. She reported this story while participating in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2020 Data Fellowship. Connect with her on Twitter @JanineZeitlin or at jzeitlin@gannett.com.

[This story was originally published by USA TODAY and Naples Daily News].

Did you like this story? Your support means a lot! Your tax-deductible donation will advance our mission of supporting journalism as a catalyst for change.