Life Under The Gun: How Compton Survives Deputy Shootings

This project was originally published in Knock LA with support from our 2023 Health Equity Impact Fund

A portrait of Keishia Brunston reveals a tattoo in remembrance of her nephew, Deondre Brunston, who was killed by the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department in 2003. July 2023.

Photo: Jayrol San Jose | Knock LA

Fred Williams Jr., whose son was killed by a Los Angeles County Sheriff’s deputy in 2020, raised his son on the same street that he grew up on in Willowbrook. At Mona Park, which sits at the end of their block, Williams Jr. recalled watching the community’s relationship with policing agencies change over the years.

“This is the meeting ground right here,” Williams Jr. said, gesturing around the park. “No matter what generation.”

Williams Jr. played in the park’s youth sports league as a child. He remembers the Lynwood sheriff’s station sponsoring his team and cheering them on at games. His positive relationship with the deputies shifted around 1995, when the Century Regional Detention Facility opened.

“The sheriffs in Lynwood started coming over here all, ‘This ‘bout to be our neighborhood, we ‘bout to take over this,’” Williams Jr. said.

Williams Jr. said he has watched his generation and the next be disappeared from the area via incarceration. Once he became a teenager, constant surveillance and harassment from deputies began. He said his son, like every other boy in the neighborhood, went through the same thing. “As soon as they landed right there, it’s been hell around here.”

Although the city of Compton has had Los Angeles County Sheriff’s deputies patrolling its streets for less than 25 years, it has had more deputy shootings than any other neighborhood or contract city where LASD is present.

Since 1984, at least 88 people have been shot at by deputies in Compton. According to the data, Black men between the ages of 18 and 30 were most frequently the victims of deputy shootings in the city.

Sheriff’s Deputies Come to Compton

From its founding in 1888 through 2000 — apart from a brief interruption in the 19th century when the population reduced to just five people — the city was policed by the Compton Police Department. Reports of corruption, manipulation of evidence, excessive beatings, killings, and even contemporary ties to the murders of Tupac Shakur and The Notorious B.I.G. within the ranks date back just as far.

In 2000, led by then Mayor Omar Bradley, the Compton City Council voted to disband the CPD. The council cited the department’s inability to curtail a wave of violence in the city, which included eight murders in 10 days. A contract for law enforcement services was given to the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department (LASD), at the time the most expensive of the 41 cities patrolled by deputies. The city council claimed the move would save residents $7.6 million annually.

Several residents who spoke with Knock LA expressed that they missed the days of the Compton Police Department.

“I had a different respect for the Compton Police Department,” Denise Tousant, whose 16-year-old grandson was killed by LASD deputies in 2009, told Knock LA. The father of her children was a Compton police officer. Tousant said that community ties like that led to more respect for residents and their kids. “You don’t have the same mentality of people from back in the day that you have now. Your child is just the subject in the street now. He’s not anybody.”

Compton continues to maintain its contract with LASD.

Yet in just 23 years, LASD deputies on the streets of Compton have shot more people than they have in any other neighborhood or contract city.

The 88 shootings by LASD in Compton is more than just a statistic. The people who were shot at, wounded, or killed have families and communities who have continued to face the effects of the trauma of the incident, both mentally and physically.

Deondre Brunston

The Brunston family migrated to Compton in the late 1960s from Arkansas as part of the Great Migration of Black Americans from the South to northern and western states. Almost a decade later, Deondre Brunston was born in 1979. He did not have an easy childhood: his mother left him and his younger brother when the boys were aged seven and two. This set off a chain of moves from household to household for Deondre. His aunt, Keishia Brunston, took him in for a time and paid special attention to him.

“I was more like Deondre’s mother than his auntie though. I just felt like he needed that extra love,” Keishia said during an interview at her Compton home. “He was loved, but I’m sure he wanted to be with his mother.”

At 16, Deondre welcomed twin boys, his first children. He had big dreams for his family and himself: he dreamed of becoming a rapper. In the meantime, according to Keishia, he was working different temp jobs and planning to go back to school.

Keishia Brunston points out bullet holes that are still present on the walls of the house where the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department fired 81 rounds at her nephew, Deondre Brunston. July 2023.

(Photo: Jayrol San Jose | Knock LA)

During the early evening of August 24, 2003, Deondre was at his aunt Keishia’s home. In a common grassy area of the complex, a young woman pregnant with his third son, Deondre Brunston Jr., argued with another woman. Keishia says the two women were fighting over Deondre. According to a district attorney report, one of the young women called 911 and reported Deondre as her assailant. Deputy William Zollo and his partner, whose identity is redacted in department records, responded to a radio call for a domestic violence incident.

Deondre was in Keishia’s apartment. When the deputies knocked on her door, he jumped out of a window and took off running down the street. He took shelter on a porch just a few houses away from his aunt’s home. Deputies surrounded him with guns drawn. One set up a video camera. Inside the home, according to LASD’s investigative report, a man who lived at the home heard deputies yelling at Deondre and ordering his family to lay on the floor.

Meanwhile, additional deputies came to Keishia’s home and asked her to come with them. She said they told her they would take her to speak with Deondre. “Had I known I was never going see Deondre or talk to Deondre, I would never went with the police anyway,” she recounted. Instead of taking her to where her nephew was being held at gunpoint, she was placed in handcuffs and put in the back of a patrol vehicle parked several blocks away. “They kidnapped me and lied to me, held me hostage.”

Deputies held Deondre on the porch for nearly an hour. A plan was hatched to send in a dog to apprehend him, with deputies Kamal Ahmad, Raymond Munoz, John Perez, and David Piquette standing by with various firearms.

Ahmad had previously shot at two unarmed men in March 2001 in the Florence-Graham neighborhood. He shot and killed 41-year-old Eddie Junior Tapia on September 10, 2015. Perez also had a previous shooting, where he shot and killed 58-year-old John Dennis Marshall on July 20, 2000.

The 2003 tape shows deputies saying that Deondre must give up or they will release a dog. The lieutenant overseeing the K-9 handlers, Patrick Maxwell, was not on the scene, according to reports and deposition testimony. Maxwell was at a party, and had consumed several drinks. From there, he gave the order to release the dog.

On the recording, Deondre says that he will shoot the dog, but also clearly states that he has not shown a gun, and encourages them to continue filming. He was holding a sandal. The deputies respond to his threats to shoot by saying they “have way more guns.”

One deputy tells Deondre to “put the gun down.” Simultaneously, the dog is released and charges toward the porch. Deondre tosses the sandal he was holding, which deputies later claimed in reports to be a gun, towards the dog. At least ten deputies opened fire.

“I’’m still just in the car you know, when I finally hear gunshots,” Keishia recalled with tears in her eyes.

As Deondre bled out on the steps, the dog was airlifted to a veterinary hospital in Norwalk where it was pronounced dead. Deondre’s body remained at the scene for hours. “That was so reprehensible that a human being is less than a dog,” said Luis Carrillo, an attorney that represented Deondre’s five-year-old sons.

“When they got ready to embalm him they had to wrap him in plastic. They had to put his face back together and things like that. He ended up having a plastic thing (covering him) that you could see through,” Keishia said. She is still haunted by the memory of a persistent odor in her downstairs bathroom. “I raised the plastic thing up, and that smell is the same smell I smell in that bathroom.”

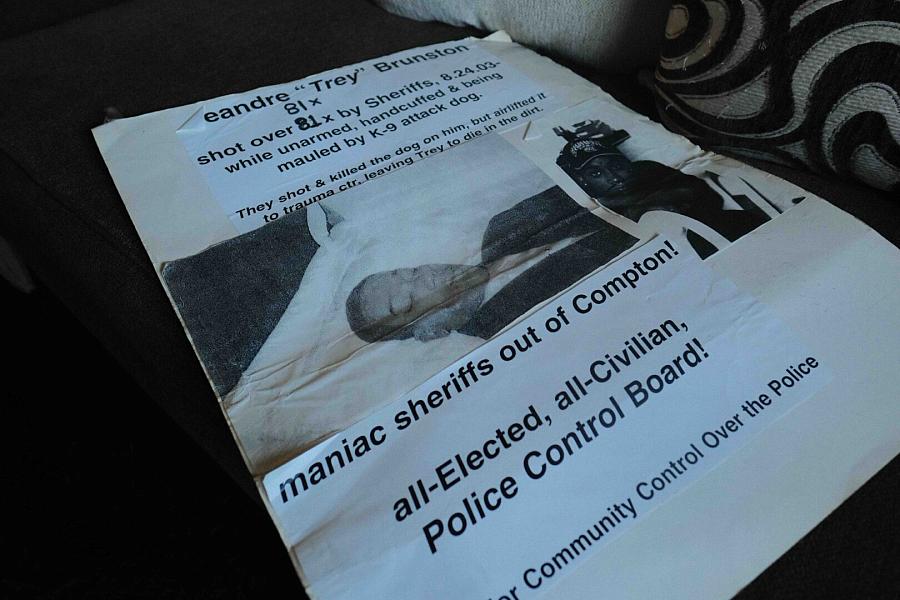

A sign made by Keishia Brunston in 2003 displays a photo of her nephew, Deondre Brunston, in a casket. Deondre was shot and killed by the Los Angeles County Sheriff’’s Department. July 2023.

Photo: Jayrol San Jose | Knock LA

None of the 10 deputies that shot Deondre were criminally charged. Former LA County district attorney Jackie Lacey’s investigators appear to have taken the deputies’ testimonies, proven to be lies from the video they took, as absolute truths in their decision to not prosecute.

An internal LASD investigation into the deputies’ actions found William Zollo, Travis Morrow, Ronald Licata, and an unidentified deputy violated policy by firing their weapons without being a designated shooter — meaning they had not been selected to fire weapons. They were given two-day suspensions without pay. Zollo was able to have that decision rescinded on appeal. Actions of the other seven deputies were deemed “unfounded” or “unresolved.”

The mothers of Deondre’s sons and Keishia filed civil lawsuits against LA County for his death. The mothers’ claim was settled for just under $445,000. Keishia’s case was dismissed after a meeting in the judge’s chambers.

“They took me in the back of the judge’s chambers and the judge told me that I better take the money — and that if I didn’t take the money, they would make sure that I lose and I would lose at everything that I do. I’ve been losing ever since.” A review of civil lawsuits Keishia has filed in Los Angeles Superior Court shows that each of her claims has been dismissed.

Keishia says that the settlement money did not repair the harm done to her family. “Families have to stick together,” she shared. “The money’s gone or you bought whatever you’re gonna buy, that problem is still there.”

Avery Cody Jr.

By 2009, Avery Cody Jr.’s family had been in Compton for over 40 years. His grandmother, Denise Tousant, came to the city in 1967 from Louisiana as part of the Great Migration of Black Americans out of the South.

Cody began living with his grandmother and father, Avery Cody Sr., when he was around two years old. Little Avery, as he was known, was the oldest of eight children on his father’s side, and the second-oldest of four on his mother’s side of the family. His siblings, parents, aunt, and grandmother each described him as the glue that kept them all together. Each remembers Little Avery taking it upon himself to care for his younger siblings when they came to visit their father on the weekend. He encouraged his brother and sisters, and even older family members, to follow their dreams, and was known for his sense of humor.

“Little Avery was the type of person who always challenged me,” his father said during an interview in the family’s Compton home. “That made me just feel like I could outdo anybody as a father, because he used to be like, ‘Can’t nobody do nothing better than my daddy.’”

Little Avery generally kept close to the house. “We usually didn’t let him out of our eyesight,” Cody Sr. said. His son was a fixture in the neighborhood, known for riding around on his bike while playing music over a speaker. Cody Sr. recalled circling the block and driving alongside behind him, always keeping an eye. But on Fourth of July weekend 2009, for the first time, Little Avery was allowed to go out with his friends alone.

At 3:39 PM on July 5, Little Avery was walking west on Alondra Boulevard toward South Poinsettia Avenue with a group of his friends. As the teenagers made their way, they crossed in front of an unmarked patrol car occupied by deputy Sergio Reyes and sergeant Dana Ellison. The officers were part of Operation Safe Streets Bureau’s gang enforcement team and assigned to a Summer Enforcement Detail. These teams have been described by deputies as targeting men of color. According to LASD’s report of the incident, Reyes and Ellison focused on the teens and believed they were gang members simply “based upon their manner of dress, gait, and gesture.”

James Nelson, an organizer at the abolitionist nonprofit Dignity & Power Now, said that describing men of color as gang members has become a common practice for deputies in the Compton area. “ID’ing you and wherever you were at, that’s what neighborhood they put you down as being from. That’s how they start off with identifying folks and put them to a territory, a gang.”

In an interview for the department’s investigation into the shooting, Ellison stated: “One thing I see is one of the dark, darker complected ones … I see his face … They’re looking at me, looking back at each other, and I’m going, ‘they look like they’re up to something.’”

The deputies called the teens over to their car. Little Avery hesitated for a second, walked toward the car, then ran.

“I couldn’t figure out what made little Avery run that day,” his grandmother Denise Tousant said. “He would always want to know why somebody is running from the police. They’re going to get caught.”

Little Avery ran about 80 feet north on Alondra Boulevard with Reyes behind him. When he reached the middle of the street, Reyes fired his gun, striking Little Avery in the back.

Avery Cody Sr. holds a photo of his first son, Avery Cody Jr., who was killed by LASD deputies shortly after his 16th birthday.

(Photo: Wilder Rush | Knock LA)

Deputies said in their statements that Little Avery had a gun. A pistol with a serial number removed was recovered from the scene by Ellison, but the DNA did not yield a match for the teen. Furthermore, surveillance video of the shooting did not line up with either deputy’s story, or show Little Avery with a gun in his hand. Video obtained by John Sweeney, attorney for Little Avery’s family, shows that Reyes touched Little Avery’s body after shooting, even though he made statements that he did not. Sweeney alleged this video proved gunpowder residue found on the teen was there because Reyes touched him, not because he had a gun.

Ellison said that during the shooting Reyes “did a pretty good job” and that he had to “give [Reyes] his props.” Reyes’ actions were found to be in line with department policy, and he was not criminally charged.

“It’s been too many times that they’ve just been slapped on the wrist, just outright interfering and interfering with investigations and so on and so forth,” Dignity & Power Now’s James Nelson said.

Little Avery’s family sued LA County for his death. As they battled the county in court, their sense of security at home came under threat.

“They [deputies] used to come in to sit in front of our house,” Cody Sr. recalled, looking out of the home’s living room window one Sunday afternoon. “I heard down at the police department they had a picture of me.”

Cody Sr. said that both he and his then girlfriend were shot outside of the home at one point. The two sought treatment at a hospital in the city of Long Beach. Yet deputies from the Compton station showed up to investigate. Because of the constant presence of deputies, the family had installed security cameras in the front. Following the shooting, deputies removed the cameras from the property. When Cody Sr. inquired after what was on the recording, deputies told him nothing had been captured. “They said a bird landed on the camera.”

In March 2011, a mistrial was declared in the civil lawsuit when attorney Sweeney revealed he had videotape proving Reyes lied on the stand about touching Little Avery’s body. Later that year, the family accepted a settlement of $500,000.

Ellison retired from the department in 2014 and receives a pension. Reyes was promoted to sergeant in 2016 and appears to have served in the department through 2020, according to salary records.

A mural depicting two children playing at the Mona Park recreation center, near where Fred Williams III was killed by LASD. July 2023.

Photo: Rodrigo Magaña | Knock LA

Fred Williams III

Fred Williams Jr. spent his formative years on East 121st Street near Mona Park. He grew up in a ranch-style home with his mother and older sister in the Willowbrook neighborhood. He says that his life was great until he turned 14, in the early 1990s.

“That’s when the pressure comes from joining the gang or wanting to be with the in-crowd,” he recalled on a cool spring afternoon in Mona Park. “And then my friends started dying. And then that’s when the reality kick in.”

Just a few years later, his girlfriend at the time gave birth to his first son, Fred Williams III. Williams Jr. said that he and his son grew up together at the home of Williams Jr.’s mother.

Williams III is described by his father, grandmother, and aunt as a laid-back, respectable young man who loved to joke around. He was very popular throughout the neighborhood and had many friends. He played seasonal basketball and football at Mona Park as a child, and enjoyed the pool and gym activities off the field.

Williams III also played youth sports, and was affiliated with a local gang that has been present in the area for generations.

“He taught me how to be a father. But at the same time he didn’t get no benefits from that,” Williams Jr. said. “That’s one of the things I regret most in life right there, exposing my son to that lifestyle.”

Williams III spent many of his teenage years and early 20s incarcerated for nonviolent crimes. His father says he never spoke much about his experiences in custody. “He always tried to not show me no type of weakness. That’s another thing I regret doing because I’m basically forcing you to be a tough guy, you know? And that ain’t how life work.”

Williams III was released on August 5, 2020, and came to live with his grandmother and father in his childhood home. His father says he was excited to get back to his normal life outside of incarceration — he was just 25 years old. Two months later, deputies shot and killed him.

A family walks past the Mona Park sign located in the Willowbrook neighborhood. July 2023. Credit: Rodrigo Magaña for Knock LA.

Photo: Rodrigo Magaña | Knock LA

Williams III spent the early evening of October 16, 2020, as he had many others like it: in Mona Park with friends. At 5:30 PM, deputies Adrian Ines and Shane Lattuca drove through the parking lot. According to a report from LA County District Attorney George Gascón’s office, the deputies say they spotted the group and made eye contact with Williams III, who broke away from the group. Ines claims he saw Williams III holding a gun and chased him through the parking lot and into the backyard of a neighboring home.

Video shows that although Williams III held a gun in his hand, he never pointed it at the deputies. However, Ines falsely stated to dispatch that Williams III pointed the weapon at him. Williams III ran through the yard and climbed on top of a shed to hop the fence. As he jumped, Ines fired his weapon at Williams III, fatally striking him in the back.

Williams Jr. recalled that following his son’s death, many people continued to stop by their home to pay their respects. “I miss him, though. We didn’t get to really bond like we could have.”

Impact of Shootings

Each of the families who had family members killed reported significant changes for the worse to their physical and mental health.

Keishia Brunston, whose nephew was killed by deputies, says his killing led to a significant weight loss and mental anguish. “I started seeing different psychiatrists. They were giving me all this medicine. I didn’t go back to work, I couldn’t. I didn’t go back to school. Just my life was just turned upside down.”

Ivery Cody was 11 years old when her older brother, Avery Cody Jr., was killed by Compton deputies. “I would describe the whole month after it, was just really traumatizing. That was the first time I had ever seen my dad cry,” she said in a phone interview. “When the sheriffs brought the belongings that they gave back to my dad, he just cried. Seeing him cry like that, that was a lot for me.”

Her father, Avery Cody Sr., said he is not the same person he was before his son’s death. “I’m never going to be that person.”

Ivery recalled the days after the shooting were filled with press conferences, but also shared she does not remember anything about the following months. “At that point [my mind] kind of went blank. I don’t remember the rest of the summer. If I wasn’t physically sick, I was mentally sick.”

Lifestyle changes for families are also common in the aftermath of a deputy killing their loved one. Brunston reported that she stopped using her downstairs bathroom because the smell inside reminded her of embalming fluid. Denise Tousant, whose grandson was killed by deputies in 2009, stopped seeing her regular barber, who she had gone to for over a decade.

“Because me and little Avery used to get our hair cut by the same guy,” she said.

Fred Williams Jr. shared that since his son’s killing, he has been diagnosed with high blood pressure, heart failure, and thyroid issues. “I got a laundry list of things that I didn’t have before this happened. Thinking back now, it’s the stress that probably caused most of it.”

During the reporting of this story, he suffered a seizure and was hospitalized.

He said his children have also changed. He described them as being more withdrawn and beginning to rebel. “It shocks your mental, and that’s tough for a kid. They don’t know how to process that.” He too said that he has become less social. “I think I shell up a lot. I spend time on my own. I try to deal with it on my own. That’s not healthy though.”

Dr. Lawrence A. Palinkas, Albert G. and Frances Lomas Feldman professor of social policy and health at the University of Southern California, said that these symptoms could indicate post-traumatic stress disorder. “The sad thing about PTSD is oftentimes what’s really traumatic is it separates us from our communities.” Furthermore, diagnoses are not limited to the families of people killed by police — they can affect entire communities.

Keishia Brunston holds up a portrait of her nephew, Deondre Brunston, who was shot 22 times by the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department in 2003. July 2023.

(Photo: Jayrol San Jose | Knock LA)

“The idea that you walk out of the house and there’s already a target on your back … because you’re Black or Latino or because you’re Native or because you’re Asian … This is why for these communities who have high rates of cardiovascular disease, disproportionately high rates of obesity, and some of the other negative health impacts,” said Dr. Alfiee Breland-Noble, founder of the AAKOMA Project, a nonprofit focused on studying mental health in youth of color.

Psychological issues that can be seen on a community level include acute stress, anxiety, depression, and PTSD.

Dr. Breland-Noble also stated that community concerns over LASD violence being historically disregarded has a negative impact on the community and is called “vicarious trauma.”

“When you have people who for years, decades have talked about these things but not been believed or their stories had been minimized or their stories have been just flat-out ignored, that has an emotional impact,” she said. “People in those communities get the message that who they are is not important.” Experts agreed that this can also lead to community-wide fear and distrust of policing agencies.

However, tightly knit communities are also more apt to build systems to address these issues. “In closely affected communities, while you’re likely to experience secondary trauma because of that connectedness, you’re also more likely to gain the kind of support that you need to deal with that trauma, particularly from people who understand where you’re coming from, who’ve shared similar experiences,” Dr. Palinkas said.

At a town hall on LASD violence hosted by Knock LA at the New True Faith Missionary Baptist Church in Compton, residents and community organizers gathered to share stories about interactions with deputies and the resulting trauma. People also offered possible solutions.

The Coalition for Community Control Over Police (CCCOP) continues to advocate for a democratically elected civilian board to oversee LASD and discipline personnel.

“The community should have absolute authority and say-so over every aspect of that agency,” said Cliff Smith, an organizer with the group. “Let the police unions run their representatives to control the board and let us run our representatives to control the board and see who can organize better. Let’s have that fight. The mechanism needs to be established because otherwise they have absolute control and there’s not even the opportunity to fight for it.”

CCCOP does not believe that policing agencies should be abolished. “If you abolish the public nature of policing, you’re left with this private policing, and if you think that having private armed military forces guarding everything is going to give you more safety or justice, I think you’re not really thinking things through or you have a different agenda,” Smith said.

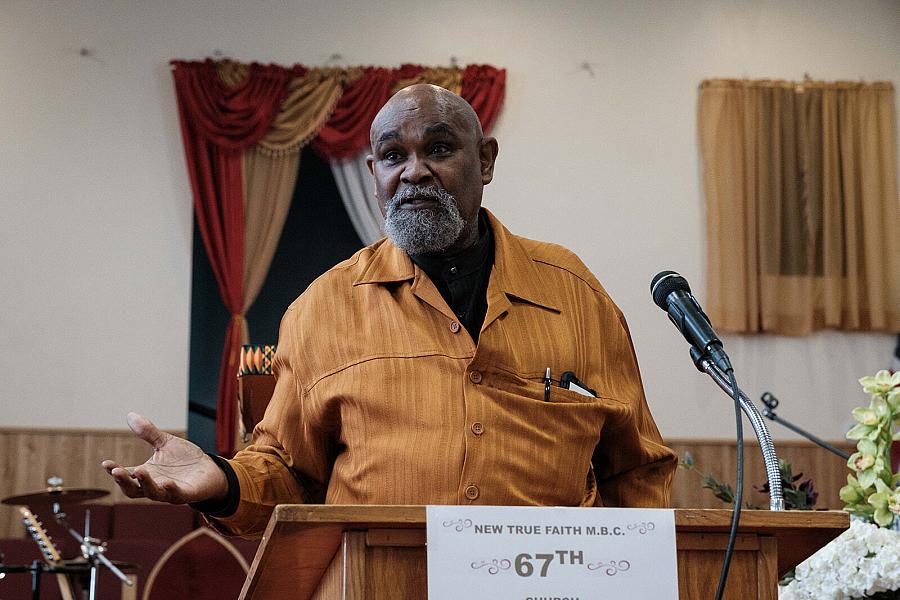

Pastor Thompson speaking during Knock LA’s Town Hall at New True Faith Missionary Baptist Church. May 2023.

(Photo: Ben Camacho | Knock LA)

However, many community organizations and nonprofits organizing to combat deputy violence are explicitly abolitionist.

Dignity & Power Now, a nonprofit dedicated to abolition of the LASD, offers several programs dedicated to providing aid to victims of deputy violence and those impacted by the criminal justice system.

“We don’t want police,” Hilda Eke, the co-executive director, said in an interview. “The first resort is policing. It shouldn’t be. … I think if I’m going through something, I want someone who understands me and sees me when I’m strong to talk to me. I don’t want a stranger with guns and pepper spray.”

Emilio Lacques-Zapien of the Youth Justice Coalition (YJC) agreed. “There are tangible demands on the ground around defunding the sheriffs, around abolishing sheriffs,” he said in an interview. Police agencies are not allowed inside of YJC buildings. Insead, the organization works with trained peace builders, people from the community who are responsible for maintaining a safe environment. “The same things keep coming up in every survey and every town hall: young people in communities need jobs. They need intervention workers and they need access to youth centers.”

Dignity & Power Now also campaigned for the closure of Men’s Central Jail and for Measure J, a ballot measure that required the county to invest 10 percent of its unrestricted revenues — estimated in November 2020 to be between $360 million and $900 million — in community-based care.

“We’re saying ‘Give us the opportunity to prove that this works.’” Eke said.

The families of those killed agree that they would like to see the people responsible for the deaths incarcerated.

“If it was up to me, I want the guy in jail,” Avery Cody Sr. said of deputy Sergio Reyes, who killed Cody’s 16-year-old son.

Fred Williams Jr. wishes the same for his son’s killer. “I want that officer arrested. But I know that’s not going to happen because they already said they’re not filing charges. They’re protected — I knew that. Protected by the government.”

Keishia Brunston would like to see a restructuring of settlement payments to victim’s families. “If they make people start taking responsibility — and not just offer this money — but take it from the officers that actually do the murders, take it out their pocket, out they household, I don’t think we will be going through this like we’re going through it now,” she said.

As the fight to right the generational wrongs of Compton deputies and the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department continues, the relationship with the community continues to disintegrate and cause harm.

“The nightmare is still going,” Brunston said. “When do it stop?”