Learning lessons: Community seeks path to health equity as COVID retains grip on Santa Maria

This is the final of four stories in the weeklong series "COVID Hot Spot: an at-risk city" produced by Laura Place for the Center for Health Journalism's 2021 California Fellowship.

Her other stories:

Part 1: Left behind: Why Santa Maria became the epicenter for COVID-19 in Santa Barbara County

Part 2: Lost in translation: Language gaps hinder critical COVID-19 outreach in Santa Maria

Ana Huynh, shown in her Chapel Street office, is the program director for Mixteco Indigena Community Organizing Project in Santa Maria.

Len Wood, Contributor

Marian Regional Medical Center's 20-bed intensive care unit is unexpectedly quiet, despite being filled almost entirely with COVID-19 patients on a recent Thursday, but that's not unusual considering the majority are sedated and intubated.

Once on a ventilator, COVID-19 patients in the Santa Maria hospital receive the equivalent of 15 two-liter bottles of oxygen per minute to stay alive, and are medically paralyzed to prevent their skeletomuscular system from using any oxygen their body can spare.

"The treatment to save their life is huge. It's one of the most severe treatments you can have," said Tim Wendling, a physical therapist at Marian. "But in this wave, I feel like they're so much more sick that they are not recovering."

Santa Maria has been a hot spot for COVID-19 spread since the beginning of the pandemic and, consequently, Marian Regional has received more COVID-19 patients than other Santa Barbara County hospitals. This month, over two-thirds of COVID-19 patients at county hospitals have been treated at Marian Regional, according to state data.

Around 40% of Santa Maria residents eligible for the COVID-19 vaccine remain unvaccinated, and since the delta variant took hold in early July, Marian Regional has seen its ICU fill with younger patients in their 20s, 30s and 40s. On that quiet Thursday, Sept. 9, all but one of the patients in the unit were unvaccinated.

"We’ve basically run at 110% for the last 18 months. We’ve stepped up to every challenge and met every disaster head-on, but we can’t run at 110% forever," said respiratory therapist Johnny Rios.

Health officials say the surge illustrates the deadly consequences of low vaccination rates, the unpredictability of COVID variants, and the need for continued partnerships to address health-care access disparities and dispel vaccine misinformation.

Of the 21 Santa Barbara County residents who died from COVID-19 in the first three weeks of September, over half resided in Santa Maria. They ranged from residents in their 70s to a football coach in his 20s, and several of them passed through Marian's ICU.

"If everybody in this community were vaccinated, we would have one person in the ICU. One," Marian Regional pulmonologist Zacharia Reagle said.

Gearing up for another surge

Santa Maria residents and Latino/Hispanic residents are the two groups that make up the majority of cases in Santa Barbara County, while inversely experiencing disproportionately low vaccination rates.

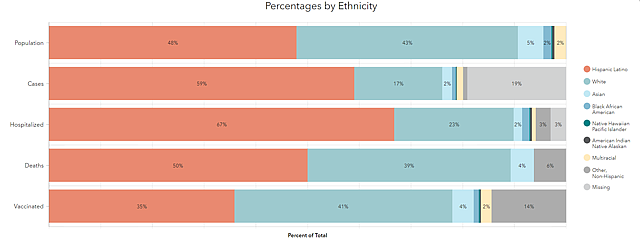

The county's most recent COVID-19 demographic study published June 30 indicates that Latino and Hispanic residents, who comprise 48% of the county population, have made up 59% of cases, 67% of hospitalizations and 50% of deaths since the pandemic began.

This Santa Barbara County Public Health Department graph illustrates how different ethnicities are represented in the county's population compared to COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations and deaths as of June 30. The Hispanic/Latino population, shown in red, is overrepresented in cases and hospitalizations but underrepresented in vaccines. Santa Barbara County Public Health Department, Contributed

"I would be surprised if there is anything out of whack with the proportions,” she said. "Even in death, it’s significantly more than what they are in the population. Sadly enough, [for] protective factors like vaccination, they are underrepresented."

To date, 45% of Latino residents are fully vaccinated compared to 51% of Whites, 49% of Asians, and 75% of Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders, highlighting the need for continued vaccine outreach and education.

"We need to stay diligent to our efforts, to our outreach, to ensure access, to ensure that community members from the Latino population are feeling protected and get the opportunity to get vaccinated, which also means education in a setting that is comfortable, that is trusted and that’s convenient," Do-Reynoso said.

Mobile vaccine clinics staffed by bilingual and trilingual staff throughout the county have strived to create such an environment for vaccination in areas that are convenient for residents in underserved communities.

Santa Maria resident Janae Sixto attended one such clinic at the Good Samaritan Emergency Shelter in Santa Maria on Sept. 15, with mother Lisa Ortiz and grandmother Graciela Martinez in tow. All three women contracted the virus in August, and Martinez had to be hospitalized and intubated.

"I thought it was just like the cold, but it's scary," Sixto said of her family's experience with the virus, from which they have now recovered. She ended up hearing about the nearby clinic and decided it was high time to get the vaccine. "We decided to get the shot for [my grandma]."

Santa Maria resident Janea Sixto, left, is accompanied by her mother, Lisa Ortiz, center, and her grandmother, Graciela Martinez, as she gets her COVID-19 vaccine on Sept. 15 in Santa Maria. After the three contracted COVID-19 in August, leading Martinez to be hospitalized, they decided it was time to get the shot. Randy De La Peña, Contributor

Vaccine demand peaked in April with 150,000 doses administered over the course of the month, but has declined significantly; around 19,700 doses were administered in July, and 27,000 doses were administered in August, according to county data.

Since then, the Public Health Department has continued collaborations with advocacy groups to target ZIP codes with a low vaccine equity metric on a scale of 1 to 4. Areas that ranked lower on the scale are determined to be less healthy based on social determinants such as neighborhood environment, access to health care and income levels.

Those involved in outreach have seen recent success, however slow. In the first week of September, the county's lowest-equity ZIP codes in Santa Maria, Guadalupe, Lompoc and Cuyama saw the greatest increases in vaccination rates anywhere in the county, ranging from 0.7% to 1.2%.

The slight uptick could mean fewer patients for local health-care workers who are feeling the emotional toll of increased hospitalizations, rapidly filling ICUs and deaths resulting from a vaccine-preventable disease.

"It’s not sustainable for nurses, not just professionally, but physically and emotionally. You go home to your own family, and you're trying to meet their needs but you feel so drained," said registered nurse Dana List. "I’ve been a nurse for 20 years, mostly in the ICU, and I've never seen so many patients go so quickly."

Turning the dial

While it's unclear what the future will bring in terms of COVID-19 cases, Do-Reynoso and local advocates are certain about the need for continued collaboration in terms of COVID-19 response and addressing other health disparities that preceded the pandemic.

One of the great successes during the course of the pandemic in Santa Barbara County has been the newfound collaboration with trusted community groups embedded in Santa Maria's immigrant and Hispanic communities such as MICOP, Central Coast Alliance United for a Sustainable Economy, and Lideres Campesinas.

Registered nurses Karen Miner, left, and Dana List check on a COVID-19 patient in Marian Regional Medical Center's critical care unit on Sept. 9. Randy De La Peña, Contributor

"That was huge, a huge huge part of successes in general, the willingness of the Public Health Department, how approachable they were," said Ana Huynh, director of Mixteco Indigena Community Organizing Project’s Santa Maria office.

While the task force was preparing to disband in early July, low case rates climbed from the single digits to double digits and then to well over 100, so they remobilized.

“We were all premature in thinking the pandemic was winding down, at least in our county,” Do-Reynoso said. “We had demobilized our big response efforts and … bam, delta happened, and we quickly had to gear up.”

While navigating the new challenges of the delta-driven surge, the Public Health Department is working on a health equity work plan with strategic steps for addressing health inequities throughout the county, developed by recently appointed Health Equity Officer Tim Watts.

Do-Reynoso has yet to announce the specific types of health inequities the plan will address outside of COVID-19, but said it should be ready at the end of the month and will increase accountability through regular reports to the Santa Barbara County Board of Supervisors, which has the ultimate say about how county funding is used.

For now, the main focus in Santa Maria will continue to be increasing vaccinations and finding ways to support community groups involved in health equity work, she said.

“We have the ingredients to turn the dial on health equity. It’s humbling, because I think this pandemic has shown us the gaps and the worries and the anxieties, and it’s humbling to know there are so many incredible partners waiting in the wings to help,” Do-Reynoso said.

At the MICOP office in Santa Maria, Huynh echoed the need to continue tackling pre-pandemic issues like housing shortages and disparities in health-care access.

"I wish we could just focus on COVID stuff, but we can't not talk about housing stuff that's related to that. We can’t not talk about health access when a woman is pregnant and expecting a baby in the middle of a pandemic," Huynh said.

In Santa Maria specifically, city spokesman Mark van de Kamp said the city's Special Projects Division, which manages Community Development Block Grant monies and other funds, is working on providing key documents and information in Spanish as well as increasing cultural competency.

"The division also does its best to participate in cultural and ethnic training, most recently attending a virtual training on Mixteco Cultural Competency which was organized by Fighting Back Santa Maria," he said.

Looking back now, City Councilwoman Gloria Soto said it was the focus on safety nets that was missing during the pandemic; residents were unsure whether they would be evicted, and whether they would be fired or lose income if they were to contract COVID-19 and have to take time off.

Over a year and a half since the pandemic began, undocumented residents continue to be ineligible for the majority of financial aid offered by the state and federal governments.

"If we had said, 'stay home for two weeks and we guarantee you two weeks pay,' if there were ways for people to access that, I'm sure that more people would have done that," Soto said. "Again, I think it just comes down to the policies not being in place."

[This article was originally published by Santa Maria Times.]