An India-West Special Report: As Death Approaches, Older Indian Americans Unprepared for the End

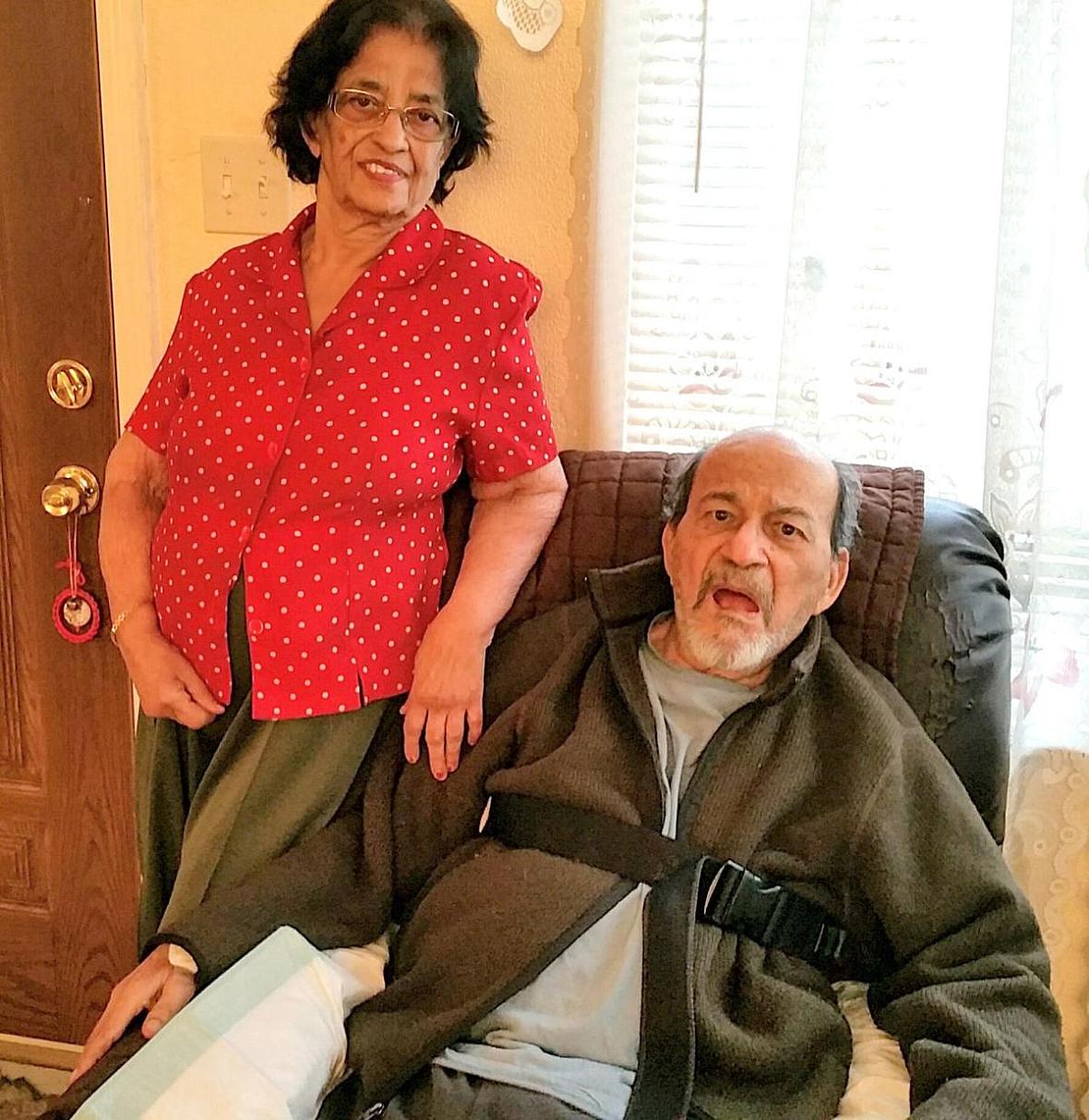

San Leandro, Calif., resident Bella Comelo, and her husband, Ernest, have written their living wills.

Viji Sundaram photo

The 88-year-old man looked gray and emaciated, the outline of his collarbones clearly visible under the loose fitting gown he wore as he lay in a narrow hospital bed in an East Bay nursing home. His eyes were closed, his mouth agape. A tube delivered both medicine and food directly into his stomach. He didn’t appear to know what was going on around him.

Nearly two years ago, aspiration pneumonia put Chandra Bhatia (his wife asked that his real name not be used) in the hospital. Since then, other health crises have kept him cycling among the hospital staff, the nursing care facility and his home. For a time, his breathing became so labored he was put on a ventilator. Now, nurses were injecting the Indian American with blood thinners twice a day.

Doctors told Bhatia’s family categorically that his many medical problems couldn’t be treated or cured. Machines and medications would likely do nothing to improve his condition. And yet, his wife had put him on “full code,” a medical term requiring doctors to do everything they could to keep him alive in the event his heart, lungs or kidneys began to fail, said their daughter.

While Bhatia was still lucid, his wife had been reluctant to have him fill out an Advanced Health Care Directive (AHCD) the hospital had given him. She erroneously thought that doing that meant she had accepted the possibility of him dying, her daughter said, a possibility she wouldn’t even discuss with her.

Palliative care, hospice care and AHCD are foreign concepts

Mrs. Bhatia’s discomfort with end-of-life care discussions is not uncommon among many older immigrants in the United States. Many of them come from countries where palliative care – making patients comfortable physically and emotionally towards the end of their lives – and hospice care — a setup where patients facing a life-limiting illness or injury are placed in with the approval of at least two doctors – are foreign concepts. And writing an AHCD is virtually unheard of.

A legal document in which people specify what medical interventions should or should not be taken if they are no longer able to make decisions for themselves because of illness or incapacity, the AHCD can be changed as often as a person wants. A living will is one form of an AHCD. Anyone over the age of 18 can prepare one, naming one person as the decision maker.

It wasn’t until 2006, following a strategic campaign led by Dr. Susan Block, a palliative care pioneer in Boston, that hospice and palliative medicine became a defined medical specialty in the United States. In 2011, U.S. medical schools began offering it as a specialty.

In India, the unflagging efforts of M.R. Rajagopal, a Kerala anesthetist and founder of Pallium India, have brought a sea change in the palliative and hospice care landscape, especially in Kerala, where community health care workers are getting trained in palliative care. Until 2015, India was near the bottom of global rankings of accessibility of end-of-life care, according to the Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance, a London-based organization.

“I think palliative care is the most ethical medicine one can practice,” asserted Dr. Suresh Reddy, who supported Rajagopal’s campaign. “It encompasses sociology, ethics, psycho-social issues, psychiatry, patient advocacy and medicine, of course. It’s a cutting edge technology.”

Reddy is the section chief and director of education at the Department of Symptom Control and Palliative Care at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas.

Last year, India’s Supreme Court passed a law legalizing “passive euthanasia,” allowing medical decision-makers to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatment from terminally ill patients. Rajagopal, while lauding the law, says he is unhappy with the term “passive euthanasia,” a feeling shared by many in India and abroad.

“The word euthanasia refers to an act (done) with the intention of ending a life,” said Rajagopal. “How can allowing natural death be given the name euthanasia even if we use the prefix ‘passive’?” He suggested that the better term would have been “withholding or withdrawing futile treatment.”

East Bay resident Immanual Joseph was quick to agree: “The word, euthanasia, has no compassion attached to it,” said Joseph, who until two years ago ran an in-home caregiver agency called Acti-Kare in Fremont, Calif.

Impediments to accessing end-of-life care

Researchers at Stanford University say that regardless of ethnicity, access to good quality end-of-life care is often impeded by a lack of financial means, poor communication with health care providers, cultural mores and family conflicts.

Although these factors cut across all ethnicities, some doctors and researchers say it is more pronounced among older Asian immigrants, especially those from the Indian subcontinent.

“It’s difficult to talk about end-of-life issues with them,” asserted Dr. Reddy, “Culturally, we are not comfortable with making living wills.”

In a few families, though, it’s the elders who take the initiative to prepare for their end. Bay Area resident Bella Comelo, 80, decided early on that she and her 87-year-old husband, Ernest, would prepare for their end, leaving no tough decision-making to their four U.S.-born children. In addition to writing their AHCD, they have bought funeral service insurance, stipulated what hymns they would like to have sung at their funeral and who should deliver the eulogy.

“At the last minute, we didn’t want our children running around trying to (second guess) what we would have wanted,” Comelo said, noting that the first time they brought up the subject of getting their AHCD done with their children, “they said they didn’t want to talk about it, it was ‘too morbid.’”

Dr. Vyjeyanthi “V.J.” Periyakoil, who directs Stanford University’s Palliative Care and Education Program, is hoping that the letter-writing project she launched in 2015 will overcome some of those hurdles. The Indian American physician gets her patients to put down on paper their “bucket list,” spelling out their wishes and goals.

The project is intended to help people from various backgrounds write a simple letter to their physician and their loved ones, making clear what they would like to do. The letter also allows participants to make their own end-of-life medical care decisions.

“Knowing my patients’ bucket list goals has prevented me from implementing medical interventions that subvert them,” Periyakoil said in an opinion piece in the New York Times last year.

Several newer nonprofits serving the Indian American immigrant community are tackling the issue through specially developed games they’ve come up with, played in a community setting that encourage people to be open about how they want to live in their sunset years, as well as how they would like to die. The Austin-based Aspire to Age is one of them. Its president and founder, Shubhada Saxena, said that she has found that community-initiated discussions on death and dying are far easier among Indian Americans than those initiated by the family. And once they understand what an AHCD is, they are willing to prepare one for themselves.

In the South Bay, the two-year-old nonprofit Sukham – a Sanskrit word for wellbeing – says its purpose is to promote the practice of living and aging well while preparing for life’s transitions. (See side bar on Sukham.) Through skits and discussions at Indian American community gatherings board members drive home the need to plan ahead.

According to AAPIdata.com, there are roughly 258,000 Indian Americans nationwide who are age 65 and older. And of the 755,221 Indian Americans in California alone, 20, 391 are over 75. This segment is either already facing end-of-life issues or is about to soon.

‘Inauspicious’ to talk about death

Dr. Jyoti Lulla, a recently retired physician at Kaiser Permanente in the South Bay and a board member of Sukham, said that she has seen many older Indian Americans look uncomfortable when the topic of death and dying come up. She said one woman clapped her hands over her ears and said, “shub, shub bolo,” (which in Hindi means please talk something auspicious).

Lulla, who from time to time does volunteer chaplaincy for the Hindu community, has heard Indian Americans say that if they talk about death, they worry that it could become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Another end-of-life care advocate said that doctors have to deal with a unique phenomenon when they are dealing with older Indian American patients, for many of whom religion plays a central role in their lives. Ingrained in the DNA of Hindus, Buddhists and Sikhs is a fatalistic attitude stemming from their belief in the law of karma. Why, they ask, should they bother to put their end-of-life care wishes on a piece of paper when the law of karma will prevail in the end.

“Yes, this karma thing is a huge barrier,” observed Kavita Radhakrishnan, an assistant professor in the School of Nursing at the University of Texas at Austin. She, along with a cohort of South Asians in Texas has done studies on the barriers that keep the community from engaging in AHCD behaviors.

Tearing family members apart

In an editorial in the Journal of the American Medical Association, Dr. Atul Gawande, author and staff writer for The New Yorker, who practices endocrine surgery at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, emphasized the importance of advance planning conversations in families.

Only with such conversations can people at the end of their lives “ensure alignment between the treatment they receive and their goals and values.

“But most people do not have these conversations with their clinicians or family members,” he lamented.

This failure has frequently torn family members apart when a loved one is dying. It did in the case ofretired South Bay engineer Saroj Pathak, one of six siblings, three of them living in India.

When her 85-year-old widowed mother, Raj Gupta, fell in the bathroom 10 years ago in her home in Indore, she slipped into a coma within minutes. She was rushed to the ICU.

Pathak said her mother had always been very independent. Time and again, she had told Pathak that should she become incapacitated, no heroic measures should be taken to keep her alive.

Pathak said it broke her heart to see her mother lying in a coma. When a doctor recommended a procedure to drain fluid from Gupta’s brain, Pathak tried unsuccessfully to persuade her siblings to let their mother die in peace. The surgeon even warned them that the procedure was unlikely to bring Gupta out of her coma.

“Three of my siblings told me I was too Americanized and that was why I wanted care to be withheld,” Pathak said, crying as she recalled the incident recently. She said they told her it was not fine for her to parachute into the country and make life and death decisions about their mother.

On the 23rd day after she had slipped into a coma, and minutes after doctors decided that Gupta should be put on a ventilator, she died.

Pathak said it’s been 10 years since her mother’s passing. Even so, “until recently” her relationship with one of her siblings had been strained because of that disagreement in the Indore hospital.

“All that could have been avoided had my mother put her end-of-life care wishes on paper” and if she and her siblings had sat together with her earlier on and had an advance care planning conversation, Pathak said.

Dying in dignity

Mrs. Bhatia spends her days at her husband’s bedside. The thought of living without her husband is inconceivable, she confided to a visitor. Among many Indian communities, a wife’s worth is still measured by the accomplishments of her husband. Bhatia is well known for his academic and social justice work.

Watching her dad’s life draw to a close, and with him clearly in discomfort, has not been easy for their daughter, who spends all her free time at the nursing home.

“My dad would not have wanted to have his life prolonged like this,” she said. “He would have liked to die in dignity.

“But my mom sees it differently. She and I are constantly fighting over this. She doesn’t even want to talk about his imminent death.”

(This article was written with the support of a journalism fellowship from the Gerontological Society of America, Journalists Network on Generations and the Retirement Research Foundation.)

Volunteer Group Helps Community in Transitioning

Sukham (a Sanskrit word meaning well-being) is an all-volunteer non-profit organization started three years ago in the San Francisco Bay Area. Its objectives were driven by the personal experiences of its six cofounders – Dr. Jerina Kapoor, Mukund Acharya, Jaya Desale, Dr. Jyoti Lulla, Mangala Kumar and Smita Patel.

“I lost my wife in 2014, and that was the inspiration for me to get interested in wanting to do something in the area of palliative care,” Acharya said.

It was Kapoor’s meeting in 2010 with M.R. Rajagopal (see main story), known as the father of Palliative Care in India, that inspired her to launch Pallium-India USA five years later. The next year, the organization morphed into Sukham (www.sukham.org). In 2017, Sukham was registered in the Bay Area as a non-profit. Nearly a dozen volunteers, largely professionals, currently serve on its board.

“There’s a need for such an organization, given that the South Asian community is rapidly growing,” said Acharya, who also volunteers at Spiritual Care Service at Stanford University and the San Mateo-based Mission Hospice and Home Care.

As part of its outreach, Sukham has made a number of presentations at Indian American gatherings, including at temples and the India Community Center in Milpitas, Calif.

“But in order for us to be effective, we need the community to be committed at every stage of their life, and not wait until they get old,” Acharya said. Sukham’s tagline, “Live Healthy, Age Well, Find Peace and Joy,” is what the organization is all about. IN other words, it’s about transitioning well.

A plan is currently under way for Sukham to collaborate with Mission Hospice, Acharya said.

Sukham is supported by donations and grants.

-- Viji Sundaram

[This article was originally published by India West.]