'I don't want to hurt nobody' | Woman with autism confronted by police

This story is part of a larger project led by Rebecca Lindstrom, a 2020 Data Fellow who explored which children are most at risk of abandonment and why.

Her other stories include:

Georgia Families Struggling With Access To Mental Healthcare Will Soon See Changes

Broken furniture, broken hopes: Georgia mom stuck in loop trying to get help for son with autism

Teen finds team to score touchdown in life: How new DFCS program could prevent child abandonment

Homeless. Jail. Sexually exploited. The Game of Life never talked about this.

Sexual exploitation, just one more danger to a mental health crisis

Georgia lawmakers commit to tackling child abandonment in next legislative session

Mom says she left note with abandoned child, police never found it

The Reveal

NEWTON COUNTY, Ga. — You can learn a lot by watching an officer’s body camera video. We wanted to know what happened in 2019 when Kayleigh, an 18-year-old with autism, ended up in a Newton County jail after refusing to leave a gas station parking lot.

Sitting on a park bench months later, I asked Kayleigh, “How was jail?” Her response was simple. “It was not good.”

But knowing she doesn’t want to go to jail, doesn’t seem to stop Kayleigh’s behavior. She’s spent time in three county jails in two years for offenses related to disorderly conduct.

“When I’m mad, I’m not going to be quiet. You’re not going to silence me,” Kayleigh said.

The past few months, many have been moved by Kayleigh’s story as we’ve tried to explain the gaps in our behavioral and mental health system, leading some parents to abandon their children to state custody.

Credit: WXIA

Kayleigh has autism, developmental disabilities and behavioral problems that make it impossible for her to live alone and be vulnerable to predators. The world’s rules on how to behave don’t come naturally and her mom says until now, therapies that could help, have been denied by Medicaid.

“It’s truly unfair for these children,” her mom, Christina Henry said.

As a result, Kayleigh has a tendency to run away. On the streets, she’s been the victim of sexual exploitation and rape. She has been homeless and she has come into contact with police again and again.

According to an open records request with the Department of Family and Children Services, of the children abandoned in the past five years, 42 percent of those that left care returned to a parent or family member. Six percent were no longer tracked because they ran away. Another three percent ended up in youth detention or jail.

There are no statistics to track what happens to the children with the same behavioral challenges, but their families find ways to keep them at home.

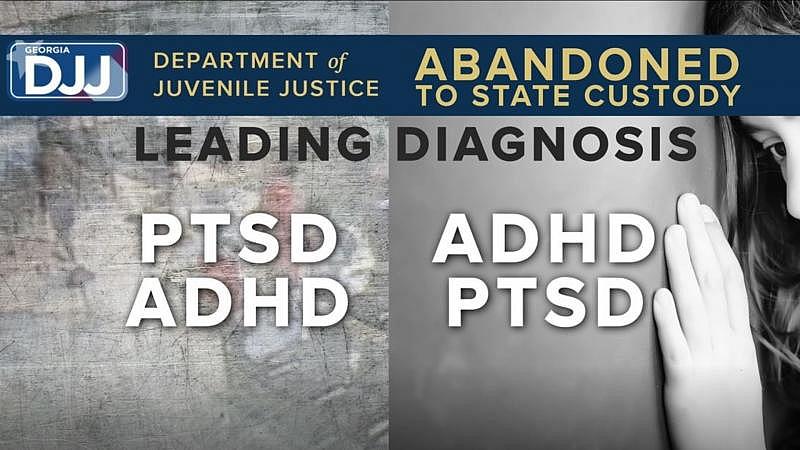

What we do know is that the Department of Juvenile Justice (DJJ) says it’s treating 60 percent of the children in its custody for some type of mental health disorder. The percentage increases to 77 percent when you look at the youths in custody for the most serious offenses.

The top diagnosis PTSD and ADHD, almost identical to the top diagnosis we found in the children abandoned to state custody.

Child welfare advocates like Susan Goico, an attorney who leads the Disability Integration Project at Atlanta Legal Aid, see it every day.

“[They end up in] the criminal justice system. We see that a lot with the kids who are in juvenile justice because they are not getting the supports that they need,” Goico said.

When Kayleigh’s outburst started leading to arrests, she was too old for DJJ. That’s why we were able to obtain body camera video showing two different calls to Newton County’s 911 – with two very different outcomes.

In the first incident, Kayleigh was seen pacing in a gas station parking lot. In the video, you can hear a witness ask the officer, “Is it a mental problem?” The officer responded, “I think it might be.”

The officer tried several times to talk with Kayleigh, but each time Kayleigh refused to give her name, hurling insults at times instead.

When her mom arrived, she denied the relationship and pushed her away. That’s when another officer decided the situation had gone on long enough.

As he approached to put her in handcuffs, she repeatedly yelled, “Don’t touch me.” The more he touched her, the more upset she became.

The body cam clips are broken, but the time stamp indicates that within ten minutes of the officer’s arrival, Kayleigh was in handcuffs.

Kayleigh was then booked in jail where she remained for three weeks.

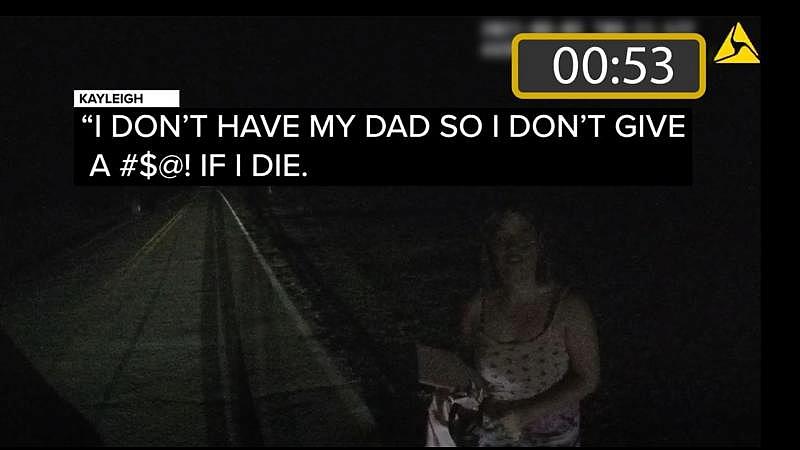

The second response came a year later. Kayleigh had run away in the middle of the night, upset about the anniversary of her father’s death.

“I don’t have my dad, so I don’t care if I die!” Kayleigh said, as heard in the body cam footage.

Credit: Newton County Sheriff’s Office

In this case, Newton County Corporal Jathan Nagrodski arrived on scene with two other officers – all with crisis intervention training.

“Most times they’re talking, they’re telling you things that will trigger them or may escalate the situation. So you have to really pick up on that," Cpl. Nagrodski said.

Triggers like the bright lights of a car or getting too close. Again in this case, you hear Kayleigh repeatedly tell the officers to keep their distance and not to touch her.

CIT is an intensive week-long course for police. And on this night, that training helped the officers to calm Kayleigh down, allowing her to think about her actions and finally accept her emotions.

“I don’t want to hurt nobody. I’m trying to fight my impulse to run,” she told Cpl. Nagrodski before falling to the ground in tears.

Cpl. Nagrodski said he appreciates the opportunity to share community resources with families that may not have known places to go for help.

“We want to get them help because going to jail isn’t going to give them support or help. It’s going to further the problem,” he said.

It’s one reason why the Newton County Sheriff’s Office decided to mandate the training for all of its deputy sheriffs, uniform patrol deputies, and school resource officers in 2020. The department is also trying to put together a dedicated CIT team to respond to calls they know are mental health-related.

According to Georgia Public Safety Training Center, 7,565 officers have received the training in the past five years. COVID-19 slowed the progression but the data indicated registrations are starting to pick back up.

[This article was originally published by 11Alive.]