Homeless. Jail. Sexually exploited. The Game of Life never talked about this.

This story is part of a larger project led by Rebecca Lindstrom, a 2020 Data Fellow who explored which children are most at risk of abandonment and why.

Her other stories include:

Georgia Families Struggling With Access To Mental Healthcare Will Soon See Changes

Broken furniture, broken hopes: Georgia mom stuck in loop trying to get help for son with autism

Teen finds team to score touchdown in life: How new DFCS program could prevent child abandonment

'I don't want to hurt nobody' | Woman with autism confronted by police

Sexual exploitation, just one more danger to a mental health crisis

Georgia lawmakers commit to tackling child abandonment in next legislative session

Mom says she left note with abandoned child, police never found it

(Image via 11Alive)

Credit: WXIA

It sounds cruel. But listen to the stories of those who have done it, and you'll quickly realize it is often a heartbreaking act of love.

The families confronted with this decision may be out of ideas for how to keep their children with autism safe as they violently fling their bodies against a wall. Parents struggle as children with dual diagnoses like impulse control disorder and intellectual disability wander out their door and into the arms of child predators.

The stories are real. For parents navigating programs that try to help, looking for the one that will actually make a difference, it is exhausting.

As part of a data fellowship with USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, 11Alive's investigative team, The Reveal, wants to show how the challenges of raising children with severe emotional and developmental disabilities can lead to abandonment.

In the past five years, 1,268 Georgia children were abandoned or surrendered due to a parent's inability to cope or the child's behavior. More than half of those children were surrendered twice - either abandoned again by their parents, another family member, a foster parent, or an institution that thought it could help.

These are their stories.

#KEEPINGKAYLEIGH

Kayleigh was born with multiple mental and physical disabilities. Early on Christina Henry knew something was wrong.

“She would projectile vomit across the room, and just kind of sometimes she would like seize in my arms and kind of her eyes would roll back,” Henry remembered.

Doctors believed the seizures were caused by a Chiari malformation, which essentially meant her brain was too big for her skull. Two surgeries addressed the deformity, but Kayleigh’s developmental delays and behavioral issues continued to get worse.

By the time Kayleigh was a teen, she’d been diagnosed with an intellectual disability, mitochondrial disorder, leaky gut, Oppositional Defiant Disorder, ADHD, and PTSD – just to name a few.

It also means Kayleigh is impulsive, has had fits of aggression, and a habit of running away. The last time she ran away, her mother found her malnourished, covered in bruises, with signs of rape and human trafficking.

Christina said it was after Kayleigh tried to kill herself – overdosing on two medications meant to treat depression – that the mother became desperate.

Believing the state could help her daughter access better treatments, she gave up custody.

“Never did I want my child to leave my home. I just wanted help. I just needed that village. And it was awful. It was such a traumatic experience. I just felt like I failed her," Christina explained.

Kayleigh, now 19, has returned home. Ironically, her mother has gone to court to win guardianship over her now-adult daughter, to remain an advocate in her medical care.

Kayleigh's struggles remain the same, except now she is at an age where treatment is even harder to get approved.

BY THE NUMBERS

Depending on who has custody of the child, there are potentially four different state agencies involved in providing care: the Departments of Community Health, Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities, Education, and DFCS.

Between them, parents argue, there’s little to no case management looking at the big picture. Just as frustrating, the child’s primary diagnosis – like bipolar disorder or autism – can greatly limit the type of services and support available.

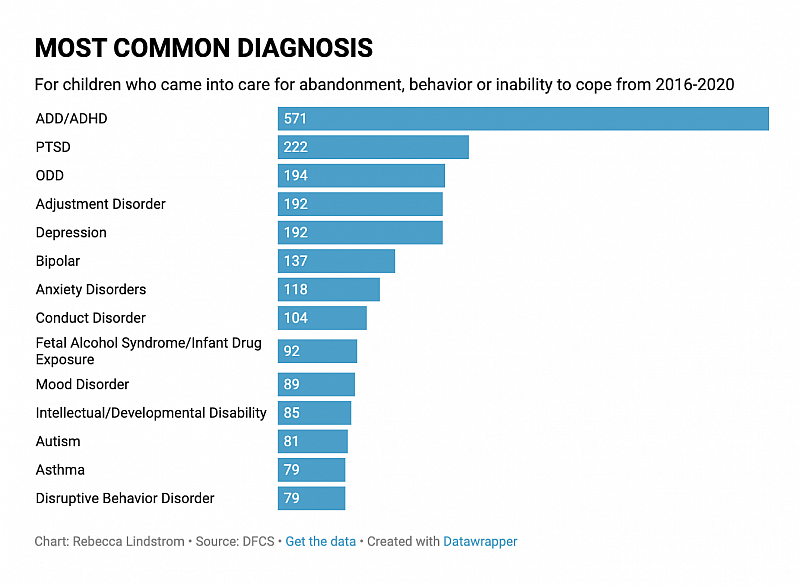

Of the children with a diagnosis listed, 58% have severe behavioral or mental health challenges, 40% have a developmental disability. More than a third come into care with both.

#KEEPINGBRADLEY

A non-verbal teen with autism sits in a residential treatment facility four hours away from home.

“I thought, this is going to be a couple of months and he’ll come back and we will have a plan on how we can help him on the daily, how I can help de-escalate and things of that nature,” April Bonaccorsi explained.

But two years later, she said her family still has none of that, despite the fact Medicaid insists that level of care is no longer a medical necessity. And it probably wouldn’t be if Bonaccorsi could find local therapists trained and willing to work with 14-year-old Bradley at home.

Unable to use words to communicate his feelings, he often speaks through aggression.

“He would wrap his whole body around your legs and bite you. And it would be to where for a year I had a piece of flesh that was just misshapen on my leg. He’s just very, very strong,” April explained.

For years, she tried to get Bradley behavioral therapy, but all she received was a slot on a waiting list. Georgia covered the service, but there weren't enough therapists available.

That’s how Bradley ended up at Springbrook Autism Behavioral, a treatment facility in South Carolina.

The Americans with Disabilities Act requires that people receive care in the most integrated setting. That means, if Bradley can be treated in the community instead of a residential treatment facility, then he should be. And it's the responsibility of the state to make sure that care is accessible to him.

April reached out to the Georgia Advocacy Office when she felt pressured by Medicaid to bring Bradley home regardless. When she pushed back, she said her insurance offered a solution.

“Well, you can give up partial custody to DFCS and then he’ll get the resources that he needs," April recalled.

She never did give up custody, and the Department of Community Health has agreed to extend his stay at Springbrook while they search for therapists to work with him at home.

But as the fight for state services continues, Bradley may not receive the in-home kind of support he needs until he becomes an adult.

SYSTEMATIC BLOCKS

One challenge is that doctors don’t always know how to express the supportive services that help keep the child healthy. It’s clear what medications or treatments might aid a physical disability, but behavioral therapies and in-home aides to help with bathing and quality of life are often not considered.

“What we see all the time is children with a more complicated diagnosis, or multiple diagnoses, fall in what I call the Grand Canyon of service gaps. Because the service systems have a hard time working together,” said Susan Goico, the Director of the Disability Integration Project at Atlanta Legal Aid.

Credit: WXIA

But improving the system will require creative incentives to bolster the state’s mental health workforce, especially in rural areas.

Parents say we also need to take a close look at what health insurance – both commercial and managed care – provides. Voices for Georgia’s Children is currently studying denials within the Medicaid system to find out why families are failing to get access to services.

Even parents who get approved for services sometimes fail to access them, either because of limited hours of availability or no providers in the areas where they live.

And just about every group that has studied this issue says we need to enforce parity, essentially equal access to mental and behavioral health services as is provided for physical medical conditions.

#KEEPINGJAYLEN

When Jaylen rocks a stair banister, it breaks. When he repeatedly jumps on his bed, the metal frame bends. But his mom Maria doesn’t know how to stop him or what he’s trying to communicate when he does these things.

The 17-year-old has autism.

Maria remembers a few years back when he started to physically injure himself. Even then, there was no way as a single working mom that she could watch him 24 hours a day.

“I said if you guys don’t help him, I’m at the part where he’s just going to get dropped off at Children’s. And I meant it. Did I want to do it? No,” Manning said, fighting back the tears. “I felt it was the only way I could get some help for him.”

Jaylen is a good example of the problem with getting government approval for services - but lacking access. He was approved for behavioral therapy to help him find better ways to communicate. But when Jaylen was younger, Maria couldn’t juggle the limited appointment times with the hours of her job. Now that she’s working from home, therapists say at 17 he’s too old.

While there are likely therapists that would work with Jaylen, Maria hasn’t found them.

“I love my son. I love him so much but it’s like am I the best thing for him? Some days I don’t feel that way," she said. "What is he learning from me? How am I helping him? What can I do? I feel helpless. I’m his advocate and I feel helpless."

ABOUT THE DATA: We asked for data on all of the children that came into DFCS custody from 2016 to 2020 for abandonment, relinquishment, child behavior, and inability to cope. There were more than four dozen diagnoses associated with those children. We categorized those diagnoses into developmental, mental/behavioral, and medical for our analysis.

The Reveal is an investigative show exposing inequality, injustice, and ineptitude created by people in power throughout Georgia and across the country.

[This story was originally published by 11Alive.]