Free phone calls for the incarcerated improve their mental health. So why are costs exorbitant?

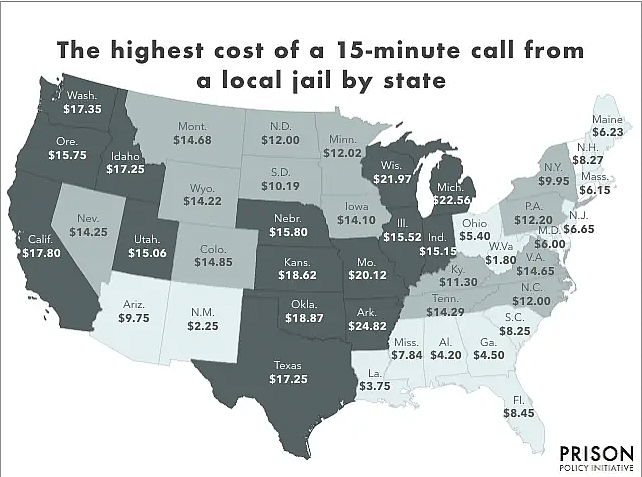

(Credit: Prison Policy Initiative)

In the 17 years Shannon Ross was incarcerated, he estimates his parents spent about $17,000 to receive phone calls from him.

These calls helped him maintain his mental health. When he was released from prison, he felt the weekly communication eased his transition to life on the outside.

“I was lucky. My family could afford it, although I know many families can’t,” said Ross, founder and executive director of The Community, a nonprofit newsletter and organization working to help recently incarcerated people transition back into society.

Ross, 39, spent nearly half of his life in prison for a murder he committed at 19. He earned a bachelor degree there. After he was released in September 2020, he became a dad and received a Master of Sustainable Peacebuilding degree from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

He credits some of his success since his release to the phone calls that kept him in close contact with his parents — hearing their encouragement and keeping him up to date on the things he would have otherwise missed, like birthdays and anniversaries.

Phone calls are critical for inmates to keep up with their family. But depending on where someone is incarcerated, the costs vary significantly: A 15-minute in-state call from an Illinois state prison is 14 cents compared to $4.80 from an Arkansas state prison.

Calls from jails are even more expensive. Prices for that 15-minute call range from $1.80 (in West Virginia) to $24.82 (in Arkansas), according to the Prison Policy Initiative.

Those costs fall heaviest on low-income people and people of color, who are disproportionately incarcerated. Some families are forced to choose between talking to their loved ones behind bars or putting food on the table.

For years, prison advocates and the American Civil Liberties Union have pushed to make phone calls inside prisons and jails for free or low cost. Cutting prisoners off from their families because of excessive costs only exacerbates mental health risks for those incarcerated and for their children, parents, aunts, uncles, brothers and sisters who remain free.

While incarcerated people are there for punishment, their families also do the time with them. Contact with loved ones behind bars is especially important for the 1.7 million children who have parents in prison, and millions of others whose parents are in jail.

Lawmakers move to make calls free

In July, two years after pledging to make phone calls free to the 13,000 people incarcerated in Los Angeles County, the Board of Supervisors issued a Dec. 1 deadline for making the switch.

The Board said the decision comes after growing pressure from advocates and attorneys who say inmates and their families — among the state’s poorest residents — are being extorted by the steep prices in jail.

In 2021, Connecticut became the first state to make all prison phone calls free. California, Colorado and Minnesota have followed.

A dozen additional states have either introduced legislation or are organizing to present legislation to have free calls in state and local facilities.

A study by The Marshall Project shows that phone calls go a long way toward keeping people out of prison after they are released, and help to improve outcomes for their children.

A research report also documented the benefits for children:

- Children who had contact with their incarcerated parents reported fewer feelings of alienation toward that parent than children who had no calls, visits or letters.

- Children who had contact with incarcerated parents were less likely to drop out of school or get suspended.

- An analysis of 92 incarcerated mothers with young children found that children who visited and talked to them on the phone were likelier to express warmth, closeness, and loyalty to their mothers.

Sharon McMurray, president of Table of the Saints, Inc., a Milwaukee-based organization that helps incarcerated people make a positive transition back into the community and family life, said the phone calls from prison are a lifeline for everyone involved.

“We know how expensive everything is now, and people make tough choices daily. One choice they should not have to make is talking to their incarcerated loved ones,” she said.

While phone calls are essential, McMurray doesn't think they should be free.

“The price should be reduced, but people should still need to earn the right to use the phones,” she said.

"Those calls are all you need to keep going.”

Over the years, I have taken dozens of phone calls from prisoners who wanted to talk to me about their cases or inform me about the abuse they deal with while incarcerated.

My prison project, “Life Correction: The Marlin Dixon Story,” chronicled the life of a young man who was sentenced to 18 years behind bars at the age of 14 for his part in the mob beating death of Charlie Young Jr. in 2002. When I was working on it, I started communicating with Dixon via letters and calls eight months before he was released from prison in 2020.

Dixon told me that the phone calls with his mother kept him going when he wanted to give up.

“When you are locked up, people on the outside keep living. They travel, have birthdays, go to parties and sometimes you don’t have anything going on when locked up. Those calls are all you need to keep going,” he said.

“We were poor. There were times when we didn’t have no food in the house, and I know it was hard for my mom to come up with the money to call me when I was locked up, but when she did, those calls helped me,” Dixon added.

The calls also helped him to talk to his daughter, who was an infant when he was sentenced. Had it not been for those phone calls, he would have never heard her voice after the visits stopped.

One last factor for moving toward free phone calls is safety for inmates and officers.

When inmates have frequent contact with loved ones, the rate of violent incidents in prisons declines by 20%, according to the 2013 study “Ways of Coping and Involvement in Prison Violence.”

If a free phone call improves the mental health of inmates and their families and makes it safer for correctional officers, it seems like a plan states should not hang up on.

What does your state charge for phone calls?

Are any efforts underway to reduce the cost of calls or make them free?

Do free or low-cost phone calls make sense?