Even in Deep Blue California, Medi-Cal expansion for undocumented doesn’t sit well with some

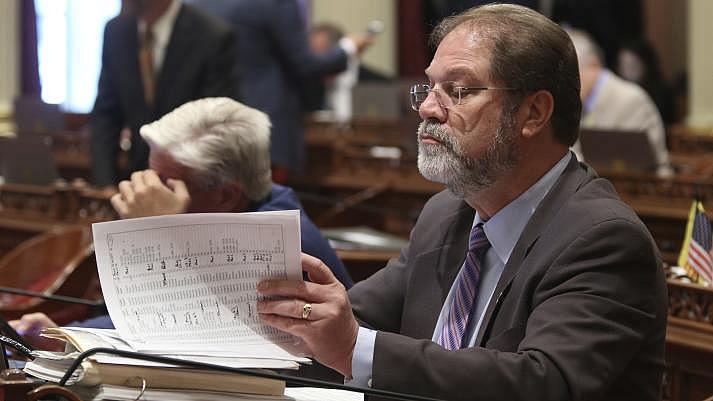

(AP Photo/Rich Pedroncelli)

It was a historic move: This summer, California became the first state in the country to offer free or low-cost health insurance to undocumented young adults who qualify.

Gov. Gavin Newsom signed the measure that will allow low-income undocumented adults ages 19 to 25 to qualify for Med-Cal, the state’s taxpayer-funded free and reduced-cost health insurance plan, starting Jan. 1. Around 138,000 people may be eligible for the coverage expansion. That’s just under 5% of the 3 million people without health insurance in the state. Immigrants, both documented and undocumented, make up 27% of California’s population of 40 million.

Although Democrats, who control the levers of power in the state, were largely united in their support for the expansion, the move was not without its detractors. Republican lawmakers and their constituents argue that the funds – the expanded coverage is expected to cost the state $98 million in 2020 — could be better spent elsewhere.

One question, going forward, is whether more centrist and independent voters will come to share those concerns. The issue of extending government-financed health insurance to undocumented residents has already become a source of heated debate in the race for the Democratic presidential nomination, with moderate candidates and voters pushing back. But that divide has been largely absent among Democrats in the Golden State.

According to a statewide survey by the Public Policy Institute of California, 63% of moderate voters supported the expansion.

President Donald Trump criticized the move, and quickly adopted it as a talking point in his reelection campaign. California doesn’t “treat their people as well as they treat illegal immigrants,” he said “It’s very unfair to our citizens and we’re going to stop it, but we may need an election to stop it.”

While Democrats have the supermajority in the California Legislature, support for the coverage expansion was not as widespread among the public as it was in the Legislature. Political analysts say the matter could become a “flip issue” alongside other immigration-related spending concerns in 2020. While some opponents say they want to push to repeal the measure, they admit it will be an uphill battle.

“My goal is to introduce the repeal, but California right now is so liberal,” said Sally Pipes, president of the Pacific Research Institute, a San Francisco-based free-market think tank that promotes “the principles of individual freedom and personal responsibility” through policies that emphasize private initiative and limited government. Pipes believes the Medi-Cal expansion is representative of a government that is too big.

“Even though many Republicans are upset with the extension, I don’t think it will make a difference,” she added. “The Dems will be in the power seat for several years to come. I wish that weren’t true. Realistically, I don’t see how the Republicans will break in on this, though.”

A poll by the Public Policy Institute of California in March showed about 63% of adult residents expressed support for expanding Medi-Cal to low-income undocumented young adults. That was up compared with 2015, when a statewide survey showed just 54% supported the idea.

However, voters also said that ensuring mental health services to those who need it and making health care more affordable were higher priorities than offering health insurance coverage to all Californians, according to a poll conducted by the California Health Care Foundation and the Kaiser Family Foundation in November 2018, when Newsom was elected.

Pipes said one of her objections to the Medi-Cal expansion was that many U.S. citizens currently are struggling to afford their health care coverage and the funds allocated to undocumented young adults instead could have helped U.S. citizens pay for their health care. Pipes also said those same U.S. citizens will now bear the tax burden of financing the Medi-Cal expansion, though they can’t even afford their own health care. However, Pipes predicts the state will continue to widen its support for undocumented immigrants, despite these criticisms.

Supporters say the expansion makes economic sense. Currently, when undocumented individuals delay care, they can end up in the emergency room. If they are unable to pay, those costs are passed on to taxpayers.

California state Sen. Holly Mitchell, D-Los Angeles, said during a May Senate session that some of the people the expansion covers would have gotten sick whether the expansion occurred or not. She said the expansion was good policy because it is treating those people in a more cost-effective manner. Now those young adults will be able to get care at a primary care office rather than seeking more expensive care at an emergency room, which taxpayers would have ended up paying for.

State Sen. Bob Archuleta, D-Pico Rivera, said he hopes this expansion is just the start to what California might do, including exploring options to provide health coverage to all undocumented immigrants.

The expansion widens the gap between California’s approach to health care and the federal government’s tack under President Trump, who has rolled back various directives that were put in place under the Affordable Care Act, including the individual mandate, transgender protections and rules on what small businesses must provide for their employees.

Kay Hillery, 83, of the Southern California community of Indian Wells, said she believes the state can’t afford to spend money on health coverage for undocumented young adults when Americans who are homeless, veterans and seniors still have great needs.

“We have a huge homeless population that need access to mental health care, and they can’t get it because it’s not funded,” she said. “We need to help our own people.”

Hillery, who identified herself as a Republican, lives in a part of Riverside County represented by state Sen. Jeff Stone. Stone, also a Republican, made similar arguments when the Legislature was considering the matter.

“We have a Medi-Cal system, a health care-delivery system, that is completely dysfunctional in the state of California. What we pay our physicians to take care of our most vulnerable populations through our Medi-Cal program is still so sub-standard that physicians won’t sign up to take the plan,” Stone said in a May Senate session.

Stone worries that providing health insurance for more undocumented individuals “will be a magnet that will further attract people to the state of California.” He said California “is willing to write a blank check for anyone who wants to be here.”

Paulette Cha, a health policy expert for the Public Policy Institute of California, said it is unlikely that the expansion will attract more undocumented individuals to California who are specifically seeking out health care.

“It’s worthwhile to compare this expansion of Medi-Cal to undocumented young adults to the 2016 expansion to undocumented children,” Cha said. “That was a much larger expansion, and we did not see an increase of immigrants because of that. The numbers have actually declined since then.”

In 2016, the first year undocumented children could enroll in Medi-Cal, just under 1 million kids were signed up. In 2017, that number was 1.59 million; in 2018, 1.57 million. If 2019 numbers continue their current trajectory, the year-end total would be nearly 1.54 million kids.

Cha said immigration is not being pushed by health care but by gang violence and poverty in other countries.

But Stone said that given the state’s limited funds, providing better health care to citizens should be prioritized first, especially those who are homeless and living in deep poverty.

“That doesn’t mean we can’t be humanitarian and take care of other people,” he said. “But it means we need to take care of our citizens first.”

Other local Republican politicians agreed.

Expanding Medi-Cal to undocumented individuals and burdening the system further is not the answer, said Orange County Supervisor Don Wagner, a Republican who served in the state Assembly for six years and was a member of the Assembly Health Committee. He said Newsom's proposal to expand Medi-Cal to undocumented adults is troubling.

"When we have finite resources, the priority should be to provide health care access to the folks who are here, have insurance and are following the rules," he said. "If these people are unable to get proper access, then that's simply not fair."

The solution may lie in public-private collaborations, Wagner said.

"Hospitals, insurance companies and the government should work together," he said. "The solutions we find should be economically viable."

Others pushed back against other health care changes signed into law by Newsom. State Sen. John Moorlach, R-Costa Mesa, said he is against burdening Californians with the individual mandate or tax penalty for being uninsured.

"Families need health care, but because they cannot fit it into their budget, they are paying the tax penalty instead," he said. "The individual mandate is regressive and has a much greater impact on a poor person's budget than a wealthier person's budget."

Moorlach, who served on the board of Cal-Optima (Orange County's Medi-Cal administrator) for four years, says the solution may lie in strengthening health care access through Medi-Cal. Moorlach also praised the Coalition of Orange County Community Health Clinics for its work in bringing health care to low-income and underserved families, including the uninsured.

"We have a model that is already working," he said, adding that the focus should be on improving health care access to those who are already on Medi-Cal.

Follow the USC Center for Health Journalism Collaborative series "Uncovered California" here.