Editor's note: This is the first of three stories examining how policy decisions and limited investment into the Virginia Department of Health led Latinos to being the most likely to get infected, hospitalized and die in the first two years of the pandemic. And how a working class immigrant neighborhood in South Richmond didn't give up.

Essential and Overlooked: How decades of inaction failed Virginia's Latinos during COVID

This project was produced as part of a larger project for USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism's 2021 National Fellowship.

Other stories in this project include:

Richmond Times-Dispatch

The protective gear shielded all but Father Shay Auerbach’s Roman collar and weary eyes as he prayed over the final hours of people who weren’t supposed to die.

Too many were Latinos. Too many were unconscious in hospital beds, shrouded with tubes thinly tethering them to the living. Too many had once filled his Sunday morning mass on Perry Street before coronavirus made huddling close in pews a potentially deadly risk.

And the risk was high. It still is.

Three months after Virginia's first case, Latinos in Richmond were 38 times more likely to be infected than white residents and 17 times more likely to be hospitalized, according to a Richmond Times-Dispatch analysis of COVID cases and hospitalizations.

What the numbers didn't capture were the essential workers left behind to survive while officials failed to protect them — the families who lingered outside of socially distanced memorial services at Sacred Heart Catholic Church to avoid mourning alone.

The data didn't publicly track how many came home to Southwood, where inescapable waves of sickness consumed the working-class immigrant neighborhood in South Richmond. Auerbach estimates it's more than dozens.

Some, he said, have yet to let themselves feel the devastation of the last 730 days.

"One has to deny so many feelings, what is happening, all the problems that exist," Auerbach said. "Because often, if we were to admit just how big those problems are, we wouldn't be able to survive."

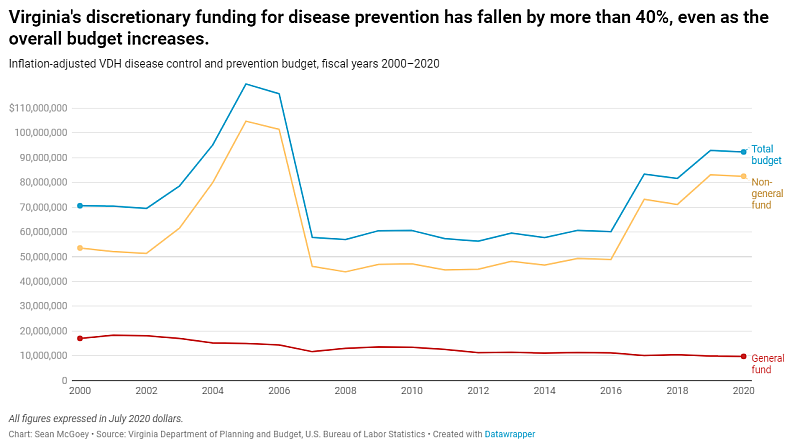

The magnitude was avoidable. In a five-month investigation, the Times-Dispatch found state leaders allowed the health department to wither and shrink for more than 20 years. Their disinvestment created a severely undermanned and underfunded public health system, incapable of fulfilling its core promise to protect the health of all Virginians.

For decades, Virginia Department of Health documents, state-commissioned reports and outside assessments increasingly warned how choking the agency's budget to the brink of collapse could prove deadly in future crises. Working class Latino immigrants, whose severe lack of insurance often left them with nowhere else to turn, would be among those paying a steep price.

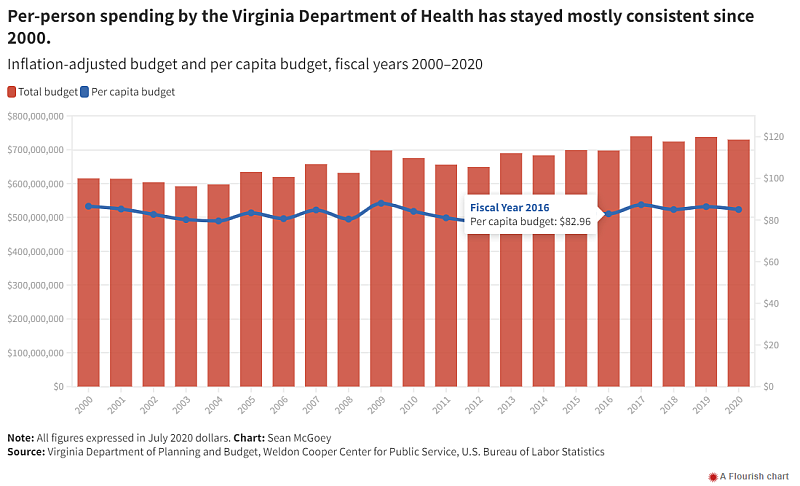

Increasing public health spending has been tied to a decline in preventable deaths and improved health in areas with little access to quality care. But in COVID's first year, Virginia was spending less on public health per person — roughly $85 — than it was in 2000, when adjusting for inflation.

VDH's inflation-adjusted general fund, which the agency has the most discretion to spend dropped by more than 25% per capita in the same timeframe.

The result was a growing reliance on unreliable federal money with strict spending guidelines. That dependence on federal dollars for close to half of its budget prevented VDH from shifting quickly to help the hundreds of thousands of essential workers in low-wage jobs who were forced to choose between quarantining or being able to pay rent.

Money is only one part of the problem.

Records prophesied the consequences of not prioritizing immigrants in prevention efforts and creating statewide language access policies. They showed how in 2009, Black and Latino children were the most likely to be hospitalized and die from H1N1, but existing language barriers and a lack of trust delayed VDH's success in reaching them.

The department’s failures to meet the needs of Virginia’s most vulnerable residents — despite its best intentions — were widely known and discussed throughout VDH and in conversations with members of Virginia’s legislative body, said Dr. Norman Oliver, the state’s former health commissioner.

“If you had asked any of us in 2018, ‘Hypothetical question, Commissioner Oliver, if we have a pandemic, who’s going to be hit the hardest?’ You know what my answer would have been?” he said. “The African American and Latino communities. Guaranteed. … and we know that that’s going to be true for the next disaster as well. Why not prepare now?”

In more than 65 interviews with VDH, immigrant-led organizations, legislators and Southwood residents, people feared a repeat of past mistakes would be inevitable if state and federal lawmakers kept dismissing the root causes behind COVID's human toll.

For now, the job of reversing the aftermath of long-term neglect continues to fall on community organizations and VDH's skeletal 3,100-person workforce — a team severely burnt out and weakened in its fight against a virus that has killed nearly 19,000 Virginians.

“It hits me right in the heart that the support for social determinants of health that’s needed in communities wasn’t enough before and it wasn’t enough during,” said Amy Popovich, nurse manager for Richmond and Henrico’s health districts who joined VDH in 2009. “I was a part of that. We were a part of that.”

Amy Popovich, nurse manager for the Richmond and Henrico health districts, prepares rapid test kits to go out to community partners at the Richmond City Health District in Richmond, Va. on January 11, 2022. EVA RUSSO/TIMES-DISPATCH Eva Russo

In 2000, a report from the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission — the General Assembly’s watchdog — wrote how VDH’s funding and staffing shortages sabotaged local efforts to perform primary functions. That includes immunizations, testing children for lead poisoning, providing services to people with HIV and reducing suicide rates.

Then in 2004, JLARC found a lack of interpreters on staff within VDH meant non-English speaking tuberculosis patients didn't receive proper medical care, which led to needing a more intensive treatment with a $25,000 price tag.

That same year, in Prince George County's rural Latino community, Alex Guzmán — a teenager at the time and a fair housing advocate from Puerto Rico — recalled seeing people living with severe liver disease in dilapidated trailers. Their best source for public health information was the local Catholic church.

After the economy collapsed four years later, the proposed budget made millions of dollars in cuts to VDH that left more than 100 positions unfilled, eliminated at least 17 positions including ones for cancer research, and closed two rural OB/GYN centers. Another $1.5 million cut in 2012 slashed funding for public health nurses, outreach workers and disease prevention health specialists who conducted screenings for newly arrived refugees.

The need for Spanish-speaking staff and Spanish translations of vital documents across VDH was again found in the agency's 2016 language needs assessment and again in 2019 when Bon Secours surveyed Richmond-area Spanish speakers about the causes of poor health in their community. Almost 60% said "language barriers."

VDH later faced a civil rights lawsuit in 2021 for lacking language options on its vaccine registration portal and for using Google Translate to relay COVID information, which once prompted a website translation to falsely tell Spanish readers "the vaccine is not necessary" instead of "not required."

The agency still doesn't track how many of its employees are bilingual or certified translators outside of job postings that specifically ask for another language to be spoken.

And two years into the pandemic, public health conversations in the 2022 General Assembly session have mostly centered on mask mandates and repealing workplace protections, not addressing the lack of paid leave and access to health insurance that accelerated COVID's wrath on Latino neighborhoods like Southwood.

Daniel Sangjib Min/times-dispatch

The 1,287-unit apartment complex sits about five miles south from where Virginia’s legislative body convenes every winter and a five-minute drive from George Wythe High School, whose controversial construction plans have largely left out the Southwood families zoned for it.

In her six years as a community health worker with VDH in Richmond, Shanteny Jackson rarely saw politicians step foot in the neighborhood so often facing the results of their decisions — even as Latinos became one of the fastest-growing populations in Virginia over a decade ago.

When Richmond City Health District opened its Southwood clinic in 2018 as part of its eight resource centers stationed across town, the number of Latinos statewide was more than 800,000.

The proximity opened Jackson up to meeting Doña Rosa Lopez, a beloved community grandmother who stands at less than five feet tall and looks out for the neighborhood kids from a wooden chair on her makeshift porch.

If Rosa tiled her head just enough, she could spot Jackson leaving the clinic and hear her shouting “Rosita! Rosita!” before their routine check-in — when Rosa shares los chismes, the gossip, of the block.

Doña Rosa laughs as she looks at a picture on Shanteny Jackson’s phone on Wednesday, November 17, 2021 at Southwood Apartments in Richmond, Virginia. SHABAN ATHUMAN/TIMES-DISPATCH

For 15 years, she’s watched people build Southwood into a place of persistence and survival. She witnessed the surrounding streets sprout into a series of Latino markets, taquerias and Dominican hair salons. She noticed when Jackson showed up one day and kept coming back, and when the health care system worked against uninsured, non-English speakers like her.

And she knew how if it weren't for Bon Secours Care-a-Van, a mobile free clinic where nearly every worker speaks fluent Spanish, Rosa wouldn’t have known her body wasn’t producing insulin.

The diabetes has worsened to the point that standing even for short periods of time shoots stabbing pain up her leg. She's unable to work but doesn't qualify for disability leave. More than 70% of Virginia's total health budget is dedicated to Medicaid, which Rosa can't apply to because she's not a citizen.

A 1996 federal law strengthened legislation to prohibit even permanent residents from accessing welfare programs aimed at helping low-income families. States have the authority to change the qualifications for Medicaid to include all children regardless of immigration status.

Only six states plus Washington D.C. have, prompting organizations like Sacred Heart Center and churches like Auerbach's, community clinics like CrossOver or the Care-a-Van and Richmond's Office of Immigrant and Refugees to fill the needs that state agencies couldn't.

But that’s become overbearing, Jackson said. Like VDH, these organizations and advocates don’t have the capacity or staff to do everything. The Trump Administration's anti-immigrant rhetoric didn't help. Its public charge rule, which threatened to deny visas or disrupt an individual's immigrant process if they sought public benefits like food stamps, only added another layer of fear to any interaction with government workers.

This included the U.S. Census Bureau.

In Southwood, eight in 10 residents are Hispanic, with more than a quarter living in poverty, per census estimates. That's likely an undercount. Residents there responded to the 2020 census at a lower rate — 41% — than almost anywhere else in Richmond, per the "Hard-to-Count" Census map.

A 2019 study published in the American Public Health Association's peer-reviewed journal found the data could affect funding for responding to public health threats and work to eliminate disparities — efforts that community health workers like Jackson have helped do for more than 50 years.

But most within VDH and across the U.S. have been volunteers, adding on the duties to their existing jobs or working part-time without benefits, said Jackson. She fought for legislation to create a statewide certification process for community health workers in 2018, which she said could have allowed for more to be officially recognized and fairly compensated. A General Assembly health committee tabled the bill.

The following year in September, VDH urged the governor to inject money in the budget for eight full-time community health workers in four health districts out of 35 total. Without dedicated staff, VDH officials wrote “there will continue to be pitfalls in access to primary care, chronic disease control and unnecessary hospitalizations.”

The agency also requested funding to build the Office of Health Equity’s infrastructure by hiring more people, citing that its small size made the office unable to “adequately reach and fully engage all corners” of the state.

While approved, they hadn't gone into effect when Virginia's first coronavirus case arrived six months later, leaving the health department with little-to-no full-time community health workers and an inability to address language needs in a pandemic that depended on accurate information.

On her regular walks to see Doña Rosa, Jackson sometimes let herself sink into the grief of what could have been if the level of outreach and community trust VDH needed was in place before 2020.

"We could've saved more lives."

Shanteny Jackson chats with Doña Rosa on Wednesday, November 17, 2021 at Southwood Apartments in Richmond, Virginia. SHABAN ATHUMAN/TIMES-DISPATCH

VDH spent years pleading in budget requests to restore funding lost in the financial crisis as the rise in uninsured patients meant more people seeking care. The agency never fully recovered.

“There’s only so much you can do with limited resources," said Dr. Melissa Viray, director of Richmond and Henrico's health districts. "If you’re looking to impact public health but you’re not putting money into the infrastructure, you can’t expect public health to be able to do more than the minimum.”

And when health districts are struggling to simply operate, Viray said, being able to focus on data and outreach can seem like a luxury they can't afford.

The data that existed in VDH’s health equity reports showed while overall health and access to care for all Virginians was improving, Latinos continued to lag behind.

The Virginia Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance system, which has provided health data to all 35 health districts since 2002, repeatedly noted that Latino respondents were the least likely to be insured, more than half didn't have a health care provider and the majority were hourly-wage workers.

These same factors were tied to being at higher risk of contracting COVID in 2020 and H1N1, or "swine flu," in 2009.

Sen. Tim Kaine, D-Virginia, who was governor during H1N1 and the former mayor of Richmond, acknowledged the role a lack of data played over a decade ago and the disconnect among local, state and federal officials in analyzing the data that existed to identify which communities were hit hardest.

"I don't think I fully understood how inadequate our data collection was in the public health space," Kaine said. "There was also the serious problem of the data existed ... but an awful lot of the local data didn't get analyzed by state officials and a lot of the state data wasn't getting analyzed by federal officials."

Sen. Tim Kaine talks with students of George Wythe High School informally after their government class meeting in Richmond, Va., on Wednesday, Feb. 23, 2022. Daniel Sangjib Min/TIMES-DISPATCH

That would once again be an issue in 2020.

Merlin Chowkwanyun, a public health historian at Columbia University, said the repetition of past errors stresses the two competing tensions in public health: health departments are the engineers to these problems but politicians are the ones who decide who gets more or less resources to best address them.

"If you don't want a problem to appear or to be acknowledged, the best way to do it is to not measure it," he said. "If you don't measure the problem, the problem isn't there."

More than 10 years post-H1N1, Latinos aren't guaranteed to be included in data. Oftentimes, race and ethnicity are recorded separately if at all, and the numbers rarely take into account the overlap of poverty, education level or immigration status in health outcomes.

Having few options meant uninsured and undocumented pregnant Latinos accounted for most of Richmond City Health District's prenatal care patients back in 2009, when Dr. Danny Avula joined the health department as its deputy director.

Until the last three or four years, however, Avula said the health district's focus was mostly on Black-white disparities because "that's where they've been the most stark."

But for Oscar Contreras, the needs were present in the 1990s when his mother flatlined in a Virginia hospital bed, pregnant with twins and in labor. The doctors didn't speak Spanish, which made communicating her pain useless. Then when they rushed her to surgery for an emergency C-section, no one could tell her husband that she was going to live.

Contreras, a Spanish radio host from Guatemala who has dedicated his life to connecting Latinos to resources, said his parents wouldn't have known what hospital to go to if it weren't for Marilyn Dunphy, a VDH worker in Culpeper County who spoke Spanish and guided them through the health system.

To this day, the trauma Hispanic patients in Virginia experience in delivery when they're not English speakers remains one of the most common issues listeners approach Contreras about.

Within the first year of the pandemic, they would become the group most likely to be hospitalized with COVID while pregnant.

Reporting for Essential and Overlooked was supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism 2021 National Fellowship and the Dennis Hunt Fund for Health Journalism.

Staff writers John Ramsey and Sean McGoey contributed to this report.

[This article was originally published by Richmond Times-Dispatch.]