This story was produced as part of a project for the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism, a program of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism.

This story was produced as part of a project for the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism, a program of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism.

![[Don Sambandaraksa via Flickr.]](https://centerforhealthjournalism.org/sites/default/files/styles/teaser_list_thumbnail_large/public/title_images/unnamed_210.jpg?itok=0OrddEpx)

Exposure to domestic abuse can change how children view relationships, with effects that last a lifetime.

![[Photo by Norbert Eder via Flickr.]](https://centerforhealthjournalism.org/sites/default/files/styles/teaser_list_thumbnail_large/public/title_images/unnamed_119.jpg?itok=Yo3MfvoO)

How one young child learned to cope with some early traumatic experiences and tell his story in a new way, through child-parent therapy.

Last week, the House narrowly passed the American Health Care Act. We've asked journalists, nonprofit leaders, and health care practitioners to share what they’re hearing from people in their cities and states.

"It’s around 10 p.m. when I call a crisis worker for victims of domestic violence in remote Northern California," writes reporter Emily Cureton. "I’m panicking, 150 miles away in Oregon. I’m really afraid someone is going to get hurt tonight."

In rural California, the state says the solutions to domestic violence require a cultural shift, that entire communities must take responsibility for ending violence against women. Now, new programs on the ancestral lands of the Yurok Tribe are trying to do that.

Domestic violence breeds shame and fear, which often keeps the abused from seeking help. Shame and fear also feed family and social dysfunction, and violence can become a normal part of life, a curse that gets passed down from generation to generation.

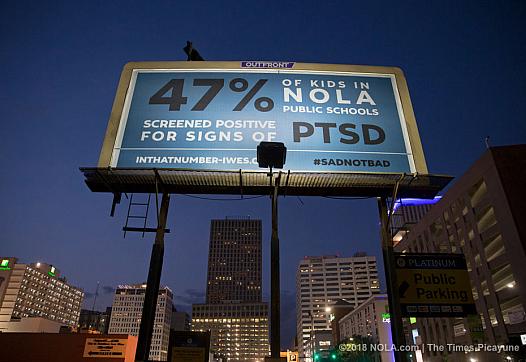

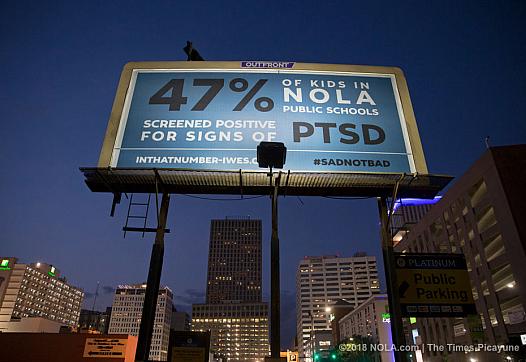

Tracking domestic violence is difficult; more so in rural areas. But in California’s Del Norte County, these calls come into law enforcement agencies at a rate two-and-a-half times that of anywhere else in the state.

Even though people in California's Del Norte County have been reporting domestic violence at a staggering rate, most abuse is suffered in secrecy. That can make it easy to overlook the fact that Native American communities are disproportionately affected.

For some residents of Del Norte County in Northern California, domestic violence is a daily occurrence. The story of Tara Williams shows just how difficult it can be to find a way out.