COVID-19's toll on more than 1,000 Mississippi's chicken plant employees

This article by Alissa Zhu was produced as a project for the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism, a program of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2020 National Fellowship.

Her other stories include:

Promotoras' a lifeline for the undocumented, sick and scared through COVID

How racism, rural living and COVID-19 created deadly conditions for a chicken plant worker

Clarion Ledger

In mid-April, an employee at one of the chicken processing plants in Mississippi’s poultry capital of Scott County noticed two coworkers showed up sick, one complaining about a headache and shortness of breath.

At that point — about one month after Mississippi announced its first confirmed case of COVID-19 and outbreaks at meatpacking plants across the country began to make headlines — his company had not yet taken precautions against the pandemic, said the worker, who asked not to be named out of fear of losing his job.

He began to feel sick himself and tested positive for COVID-19 a few days later. He had to take more than three weeks of unpaid leave as he battled the virus alone at home. His temperature got so high he said he felt like he “could have exploded.” He didn’t eat for 10 days. He could barely breathe.

“I was so afraid to die alone,” he said in Spanish. “My only wish was to see my family (in Mexico), to forgive me for not being able to see them …. I was sad about dying alone without anybody noticing.”

The worker is among more than 1,200 Mississippi chicken plant employees who contracted COVID-19 since the onset of the pandemic, according to data obtained from the Mississippi State Department of Health. At least eight workers died from complications due to the virus, according to the health department.

While the state’s top health official says there’s little evidence of significant spread at chicken processing facilities, some employees and workers' rights advocates disagree.

Advocates say poultry companies prioritized profit over people and didn’t implement protective measures against the coronavirus until the pandemic began to take a dire toll on workers, who are overwhelmingly Black or Latino, and work in grueling conditions for little pay.

Chicken companies said their top priority is the health and safety of their workers and that they have implemented safety measures that meet or exceed guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

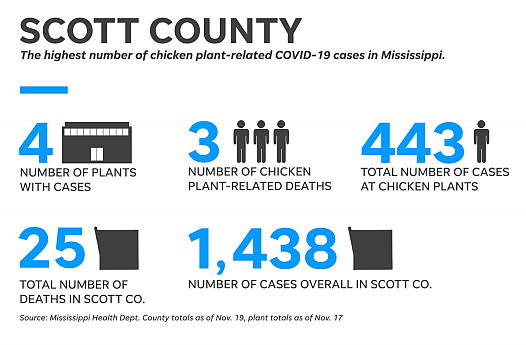

In Scott County — where poultry powerhouses Koch Foods, Peco Foods and Tyson operate processing facilities — the health department recorded 438 COVID-19 cases among chicken plant workers through Nov. 17. That’s equivalent to three poultry plant worker cases for every ten COVID-19 cases in the entire county.

“We’ve seen all across the U.S. these factories are super dangerous,” said Jessica Manrriquez, deputy director of the Immigrant Alliance for Justice and Equity of Mississippi. “Not in terms of just the normal work they have to do. During the pandemic, these places are breeding grounds for folks getting sick with the virus.”

How much transmission happened in plants?

State Health Officer Dr. Thomas Dobbs has said there’s little evidence to show that significant transmission happened in the facilities while people were at work. He said it’s more likely that sick employees were exposed to COVID-19 at home or while carpooling to work.

“When we had these outbreaks we actually sent nurses into each chicken plant to investigate and understand what was going on,” Dobbs said. “And what we would learn pretty commonly (is) that it would be four people who were roommates in a house, but on a (factory) floor they were separated by great distances.”

However, Julia Solorzano, attorney with the Southern Poverty Law Center, said it’s “outrageous” to think that workers are contracting the virus at home and not at work. At chicken processing plants, social distancing is difficult, if not impossible to maintain. Plus, attendance policies and a lack of sick leave incentivized employees to go to work even while ill, she said.

“They’re blaming the victims of this pandemic for living in conditions that their low wages are forcing them to live in,” Solorzano said.

Dobbs visited the Peco Foods plant in Bay Springs when Jasper County and six other counties were seeing unusually high per capita numbers of coronavirus cases in May, recalled Bay Springs Alderman Bob Cook.

The hotspots appeared to be tied to high rates of transmission among poultry plant workers, Dobbs said at the time. To address the spread of COVID-19 in those counties, the state provided personal protective equipment to workers and implemented masking requirements at businesses and public events. This was long before Gov. Tate Reeves temporarily ordered a statewide mask mandate in August.

Cook said the combination of community restrictions and enhanced safety precautions at the plant — albeit implemented after urging by local leaders — “saved some lives” and flattened the number of cases.

But not before there were deadly consequences. In one case, two members of the same family worked at the chicken plant in Bay Springs and contracted COVID-19. Another member of their household also ended up getting sick and dying from the coronavirus, he said.

“After that was brought to light, the poultry plant started taking things much more seriously,” Cook said. “(It was) affecting not only employees, but some employees’ family members.”

Health department numbers and interviews with workers and community organizers show that what Cook saw in Bay Springs mirrored other poultry plants across Mississippi.

While the rest of the state has seen the biggest spike of COVID-19 cases in December, the most significant surge of cases among chicken plant workers came in April and May.

Groups of women began sewing masks to donate to chicken plant workers because companies weren’t providing personal protective equipment, several weeks into the pandemic. Companies eventually mandated workers to wear masks, started checking temperatures at the door and installed plastic barriers at break room tables and along the assembly line.

Data provided by the state health department shows that in April, at the height of the outbreaks at poultry plants, there were 558 COVID-19 cases in a month. The numbers later tapered. The health department only reported 12 cases in October in chicken processing plants.

Out of the nine companies that had COVID-19 cases at their Mississippi plants, four responded to requests for comment: Koch Foods, Peco Foods, Tyson and Sanderson Farms. Only Sanderson Farms agreed to an interview.

All four companies said they now require workers to wear masks and check the temperatures of anyone entering the plant. They have also relaxed their attendance policies, installed dividers to separate workers, stepped up sanitization procedures, educated employees about social distancing and hygiene, and some have started paying employees sick leave.

Attorney Roger Doolittle, counsel for United Food and Commercial Workers Local 1529, a union which represents a few thousand chicken plant workers in the state, said like a lot of industries in Mississippi, poultry companies have changed policies and implemented measures during the pandemic, but were late to start.

“I think a lot of them were late to the game because it costs money to take preemptive measures,” Doolittle said.

“Cheto” Reyes, 61, a Koch Foods employee said he got sick at work in March, before any protective measures, such as mask requirements and temperature checks, were implemented. Reyes asked to be identified by a nickname because he fears losing his job.

“I remember still feeling so weak I couldn’t even walk straight. I felt like I couldn’t breathe,” he said in an interview conducted in Spanish. Reyes spent three weeks quarantined in his bedroom, but that didn’t stop his wife, grandson and grandson’s wife from getting sick too.

He returned to work after two weeks. Reyes said he wasn’t penalized for missing work, but he didn’t receive any sick pay either.

Reyes said after he became ill, others at the plant got sick as well. Two of his co-workers died from COVID-19 complications. He said those deaths likely pushed the company to begin requiring masks at work and to install clear plastic sheets to separate workers standing side by-side.

However, workers are still standing about two-feet apart and face-to-face with no barrier between, Reyes said. The company distributes masks to workers on some days, but not every day, he said.

A statement from Koch Foods said the company encouraged employees to bring masks from home at the beginning of the pandemic when they were in short supply. The company began supplying masks to the facility by March 24 and was able to procure enough to supply all employees by the third week of April.

Koch Foods also started checking temperatures of employees on April 1, following federal guidance on the permissibility of employers to take the temperatures of workers, according to the company’s statement. Thermometers were in short supply and were not provided to all locations at the time.

Response times to the pandemic varied from company to company. Representatives from Tyson and Sanderson Farms both said they began preparing to face COVID-19 as early as January, when the threat of the coronavirus had not yet reached global pandemic proportions. Peco Foods did not provide a timeline of their response.

Black, Latino essential workers treated as ‘disposable stock,’ expert says

Black and Latino residents have been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic across the country and it’s no different for those who work inside Mississippi’s chicken plants. About 63% of the poultry plant-related cases have been among Black employees and 21% among Latino workers, according to data from the department of health. In comparison, 38% of Mississippi’s overall population is Black and 4% is Latino, according to Census data.

Black and Central American immigrant workers face unique challenges when it comes to health and healthcare due to their race, socioeconomic status, place of residence, and in some cases, their language skills and legal status.

“What COVID-19 has done… is really bring to the forefront those structural inequities that have existed for decades,” said Dr. Sergio Aguilar-Gaxiola of the University of California Davis Center for Reducing Disparities.

“Meatpacking workers, farm workers, service workers have been seen as disposable stock,” Aguilar-Gaxiola said. “(The perception is) they are less than… They are here just to do the job we want them to do. If they get infected, who cares?”

It’s no coincidence that poultry plant workers represent some of the most vulnerable groups in the community, said Angela Stuesse, a professor of anthropology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill and author of Scratching Out A Living: Latinos, Race, and Work in the Deep South.

The poultry industry seeks out workers who are easily exploitable, Stuesse said.

“The industry is strategically locat(ed) in places where there’s generational poverty and a lack of access to education as means for moving to a better job,” she said.

For several decades chicken plants were mostly staffed by Black women until the demand for chicken increased and workers began organizing for more rights, Stuesse said. In the 1990s, companies began to recruit immigrant workers from Central America.

Today, Black workers make up about 68% of the workforce in the poultry industry in Mississippi, according to data compiled by the Economic Policy Institute. However, Stuesse said, it’s hard to get an accurate count of the number of foreign-born workers. It is estimated at 8.4% by the same dataset but that likely “significantly undercounts” undocumented workers, she said.

“When our Black and brown communities do well, we all do well,” said Jamila Taylor, director of health reform and senior fellow at the Century Foundation. “Especially in the backdrop of this racial reckoning, I would hope we are moving to a place where we are operating as a unit.”

State health officials have said that by the time they looked at how the COVID-19 pandemic was impacting communities of color, Black residents were contracting the coronavirus at much higher rates than expected.

“We were astounded, we actually had to go back and double check we didn’t make a mistake,” Dobbs said during a virtual town hall hosted by Tougaloo College, a historically black, liberal arts college in Jackson.

The health department has reached out to hard-hit communities and partner organizations to distribute protective equipment, host testing events and provide information, Victor Sutton, director of preventive services and health equity, said in an email.

“Government agencies have not historically been transparent or helpful to the communities, and it is key and important that we as the Mississippi State Department of Health continue to work to build trust within these communities,” Sutton wrote. “It is important to build partnerships with leadership in these communities and to work together to identify and address their needs.”

What are companies doing?

With the poultry industry in particular, Dobbs said the state health department has met with company leaders, inspected facilities and in some cases, set up testing sites nearby.

“They have taken additional steps as far as mandating masks, having plastic barriers between, having hand hygiene, putting barriers between them in the break rooms and that sort of thing,” Dobbs said “They’re dedicated, from my observation, to try to prevent transmission within those plants.”

He said many of the companies have been proactive in trying to prevent transmission at the plants, and some companies have been more responsive than others.

Dobbs appeared to be referring to Sanderson Farms, which is the largest chicken company in the state with about 7,000 Mississippi employees and has fewer COVID-19 cases than one of its smaller competitors.

Mike Cockrell, CFO of Sanderson Farms, said his company has prioritized worker safety from the very start.

Cockrell said the company began preparing for COVID-19 in January, when most reported cases were still in China, by speaking to medical and public health professionals about formulating a response plan. In March, they sent memos out to employees, first about travel restrictions, then about how to mitigate the spread of the virus. By early April, despite a global mad scramble for masks, they had secured personal protective equipment for workers.

Twice a day members of a pandemic response team meet to review what’s working or not, Cockrell said. Workers can call a hotline to speak to a nurse if they have concerns.

“Communication is what has allowed us to operate our plants, for the most part, as normal,” he said.

Cockrell said he would feel safe working at one of Sanderson Farms’ plants.

“I think I'm safer going to one of our processing plants than I am going to a big box store today because I know what we’re doing,” he said.

‘It makes me scared to death.’

Even though company policy requires workers to wear masks, not everyone follows the rules all the time, Debra Thomas, an employee at Koch Foods said in September.

She sees her coworkers take their masks off in the breakroom and the bathroom, Thomas said, and that worries her. Two other women at work became so ill from coronavirus that they had to be hospitalized, she said.

“People I know are dying from it. I see the lady working with me getting it. It for real, it ain’t no joke,” she said.

Thomas said she doesn’t use the bathroom at work anymore and she never lingers in the breakroom. She uses the restroom right before work, and goes across the street to a store if she needs to take another bathroom break. The mask stays on tight during her entire shift.

She doesn’t take any risks when she comes home to her children either.

After every workday she has a routine. Before entering her house she sprays herself down with Lysol. She leaves her shoes outside and hops into the bathroom for a shower. Her work clothes go into a plastic bag that she transfers to the wash as soon as possible.

Thomas said she follows her own set of stringent safety rules because she can’t count on her workplace to enforce all safety measures.

“It makes me scared to death,” she said. “You’re trying to work, but you can’t focus. You’re focusing on whether you’re going to catch it or not. But you need the money at the same time …. I got bills, I got responsibilities. I can’t get nowhere without the money.”

Alissa Zhu formerly reported for The Clarion-Ledger in Mississippi. Maria Clark reports from New Orleans for The American South.

This article was produced as a project for the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism, a program of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2020 National Fellowship.

[This story was originally published by the Clarion Ledger.]