The costly toll of dead-end drug arrests

This story was produced as part of a larger project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism's 2021 National Fellowship.

Other stories include:

Kim Foxx’s ex-trainer caught up in ‘unending cycle’ of drug arrests; ‘It breaks my heart’ by Frank Main, Jared Rutecki and Casey Toner

Oregon’s the first state to ticket narcotics users, but reform has yet to live up to what was promised by Frank Main, Jared Rutecki and Casey Toner

Dead-End Drug Arrests: How We Reported This Story by Jared Rutecki and Casey Toner

New Illinois law gives cops choice not to jail people for small amounts of drugs — a follow-up to our ‘Costly toll of dead-end drug arrests’ investigation by Frank Main, Jared Rutecki and Casey Toner

Raymond Galloway, a line cook at a Chicago soul food restaurant, wasn’t able to work regularly for about six months because of legal troubles stemming from two arrests for possession of small amounts of heroin this year — both of which were quickly thrown out.

Pat Nabong / Sun-Times

Raymond Galloway, a 48-year-old line cook at a Chicago soul food restaurant, got arrested on the West Side twice this year carrying small amounts of heroin.

Both times, the courts quickly tossed out his charges. Cook County’s judicial system, under an unwritten policy that even Cook County’s top prosecutor calls a failure, routinely dismisses minor drug possession cases — but usually not until after those arrested spend a few weeks in jail, often with life-changing consequences.

Galloway is among tens of thousands of Chicagoans — mostly Black men — who have been jailed in the past two decades on drug charges everyone knew from the beginning were never going to stick, an investigation by the Chicago Sun-Times and the Better Government Association has found.

The police knew. The prosecutors knew. The judges knew.

Yet no one has put a stop to it.

Along with their freedom and their dignity, Galloway and others have lost jobs and homes and relationships. They’ve had to pay thousands of dollars to get their cars out of the city’s impound lot. And they often struggle to pay bills while fighting their addictions.

“I can’t pay the phone bill,” Galloway said. “I’m two months behind on my rent. Child support, I got kids to take care of. I can’t do anything.”

In addition to the human toll, this constant churn of dead-end arrests costs taxpayers tens of millions of dollars every year.

“What a waste of time and resources to drag people into court on a drug charge and dismiss it,” said Ben Ruddell, director of criminal justice policy for the American Civil Liberties Union of Illinois.

“What’s the point?”

Most cases under a gram dismissed

The BGA and the Sun-Times analyzed 280,000 drug possession cases using nearly two decades of court data compiled by The Circuit, a collaborative of news organizations including the BGA and Injustice Watch. The examination disregarded arrests involving marijuana, which has been decriminalized in Illinois.

About half of the drug possession cases in Chicago between 2000 and 2018 — about 140,000 — were dropped at their earliest stages.

And that dismissal rate has soared in the most recent years.

Juan C. Johnson has struggled with heroin addiction since working as a trainer whose clients included State’s Attorney Kim Foxx. Ashlee Rezin / Sun-Times

For instance, an examination of all 10,480 cases from 2018 in which drug possession was the most serious charge found that a whopping 72% were tossed out.

These dead-end arrests are the result of a longstanding, commonly understood rule among prosecutors not to pursue criminal charges against anyone caught with user-level amounts — around a gram, according to interviews with judges, prosecutors and defense attorneys as well as an examination of hundreds of case files.

Under Illinois law, all drug possession cases involving less than 15 grams — as little as a single pill of Xanax or a grain of heroin — are lumped together under the same felony offense, making it impossible to isolate statistics for specific quantities.

To examine the lowest-level cases, the BGA and Sun-Times reviewed a random sample of 400 arrest reports from 2018 to determine the exact weight of the drugs listed.

About 95% of the cases involving less than a gram, about the weight of a paperclip, were dropped.

To give a sense of how much a gram of heroin weighs, it’s about the same as this paperclip. Brian Ernst / Sun-Times

‘A colossal waste’

It’s difficult to find anyone involved in this catch-and-release system who’s willing to defend it or end it.

Cops say they’re obligated to enforce the law.

But even Cook County’s top prosecutor — State’s Attorney Kim Foxx — acknowledges the futility of the endless cycle of arrest and release, which she says has been the norm at least as far back as when as when she first began prosecuting such cases in 2008.

She said young prosecutors almost felt as though they were being subjected to “hazing” when they brought drug possession cases to court.

“My colleagues were, like, ‘You’re never going to get a finding of probable cause on anything less than a half a gram,’ ” Foxx said.

After she was elected state’s attorney in 2016, she told her prosecutors to release low-level drug users within days. Previously, she said, that often took weeks.

When people are arrested, they have a bail hearing. Then, the case goes to a preliminary hearing.

“My directive was: If we knew these cases were going to be dismissed at the preliminary hearing stage, we would try to dismiss them [earlier] at the bond hearing,” she said.

“Just transporting the people to the courthouse, the sheriff and all, it was a colossal waste to me on a case that was just getting thrown out.”

But the steady flow of drug users into courtrooms continues.

The Chicago police have begun a diversion program to allow some people caught with small amounts of drugs to go into treatment instead of the courts, but the program — which began in 2016 — benefits only a small fraction who meet the stringent entry requirements.

Over the past three years, Illinois lawmakers have unsuccessfully proposed downgrading possession of small amounts of drugs from a felony to a misdemeanor. But the idea follows a national trend of states reducing drug-possession penalties.

In the boldest such reform, Oregon voters recently approved a measure that decriminalizes possession of small amounts of drugs.

Raymond Galloway says that, even though his two drug possession arrests were soon thrown out, he was unable to work regularly for more than six months, resulting in more than $6,000 in lost wages. Pat Nabong / Sun-Times

‘It was dust, man’

Galloway said he first snorted heroin a few years ago while he was partying with friends. He’d done cocaine before and was curious about heroin.

“I was, like, ‘Damn, this got me feeling good,’ ” Galloway said.

Then, he got arrested for heroin possession — twice.

First, he got caught with 0.2 of a gram of heroin in April.

“It was dust, man,” Galloway said. “I was, like, ‘Y’all taking me to jail for this?’ ”

He had to stay in a halfway house until that case was dropped.

In June, he was arrested for possession of two grams of heroin and ordered to live in another halfway house. That case was tossed out, too. The judge let him return to his Uptown apartment but ordered him not to leave except to get his daily methadone treatment to keep from going into a withdrawal.

“The withdrawal from heroin would kill me,” Galloway said.

Because of his arrests, Galloway was unable to work regularly for more than six months, which he said cost him more than $6,000 in lost wages.

In late September, a judge lifted Galloway’s stay-at-home order.

He returned to work at a soul food restaurant, where he prepares yams, collard greens and other comfort food.

His boss said his absence had “really messed things up.”

Galloway is now free on bail while he awaits trial for his 2020 drug-selling case.

His legal woes are an exception in the majority of drug cases: For seven of 10 people charged only for drug possession, it was their first and only charge since 2000, records show.

The BGA has filed suit against the Chicago Police Department on grounds it failed to turn over body-camera footage of Galloway’s arrests within the time required by law. But the BGA was able to obtain another video of Chicago police drug arrests through the Illinois Freedom of Information Act.

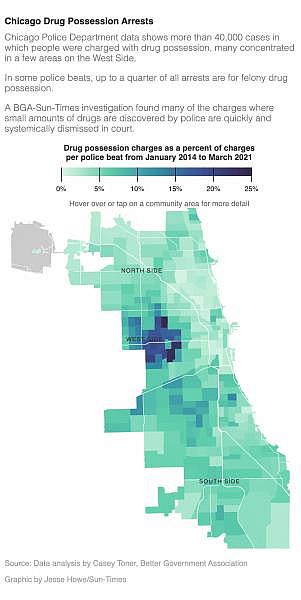

West Side drug arrests

Source: Data analysis of Chicago arrest data by Casey Toner, Better Government Association Graphic by Jesse Howe/Sun-Times

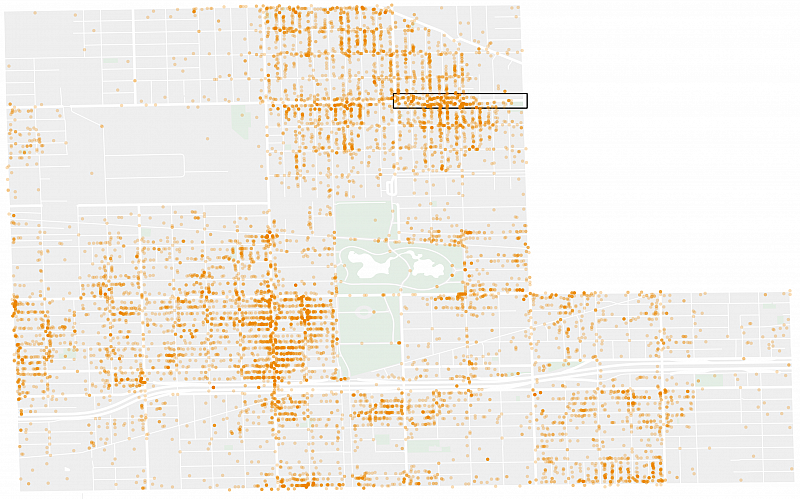

All of Raymond Galloway’s arrests occurred in the West Side’s 11th police district, which is about five miles from downtown Chicago.

The 11th district has twice the drug arrests of any other police district in the city.

In a half-mile radius of the 3400 block of West Chicago Avenue in West Humboldt Park — where Galloway was arrested in April — officers have arrested more than 500 people for drug possession since 2014.

In just four police districts on the West Side — the 10th, 11th, 15th and 25th — there have been more than 23,000 drug possession arrests since 2014.

In the remaining 18 police districts, there were only 17,000 drug possession arrests over the same period.

The blocks surrounding Garfield Park are hotspots for drug sales and violence in Chicago. Garfield Park is in the center of the 11th police district.

The Eisenhower Expy. runs from the suburbs, through the West Side just south of Garfield Park and into downtown Chicago. Sometimes, it’s called the Heroin Highway.

Every day, people pull off the highway to buy drugs in open-air markets on side streets, alleys and vacant lots on the West Side. And every day, some get arrested for having small amounts of heroin, cocaine or illicit pills.

Movie palaces, fur stores

Madison Street and Pulaski Road about 50 years ago. Sun-Times file

Decades ago, movie palaces and fur stores anchored a glittering hub of commerce along Madison Street just west of Garfield Park. And about a mile away, Sears once operated a massive distribution center. There were plenty of jobs.

In the late 1960s, riots triggered by the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. burned out sections of the West Side that were never rebuilt. White people fled, and their money went with them.

Sears closed its Homan Square facility in 1987, moving its headquarters to the Sears Tower. Today, the West Side’s population is poor and predominantly Black. Life expectancy in West Garfield Park is 68 years — 15 years less than in mostly white Edison Park on the Northwest Side, according to census data. Jobs are scarce. So are grocery stores.

This is the “constellation of forces” that produces open-air drug markets like the ones on the West Side, according to Dr. Anthony Iton, a national expert on the effects of poverty and racism on public health.

“Let me take away your education, let me take away maybe one or both of your parents, let me take away your bank account, your transportation, let me just sort of constrain your choices so dramatically but in a way that you actually see opportunity, but you can’t get to it,” he said.

Dr. Anthony Iton. Provided

“That causes enormous stress, and the more stress you have, the more you’re likely to seek ways of short-term alleviation of that stress,” said Iton, senior vice president of health communities with the California Endowment.

‘Good dope sells itself’

Michael Pitts, 36, a Four Corner Hustlers gang member serving a 12-year federal drug sentence, said a West Side heroin operation staffed by four or more people can bring in up to $10,000 a day.

“Good dope sells itself,” Pitts said by email.

And there’s no shortage of sellers. Pitts, who sold heroin in West Garfield Park, said somebody is always “ready to hustle or ‘jug,’ as we call it, once a spot is gettin’ money.”

In a typical open-air market on the West Side, everyone has a job: Some people are lookouts, someone works “security” and holds a gun, and someone else supplies heroin, cocaine or pills to the sellers on the street.

Other parts of the city — even those with similar economic problems — don’t have the same levels of street dealing as West Garfield Park, Humboldt Park, Austin and North Lawndale, all on the West Side.

South Side gangs used to deal drugs outside the Robert Taylor Homes and other public housing complexes. But the high rises were torn down, and times have changed. Much of the street dealing on the South Side is gone, said Roberto Aspholm, author of “Views from the Streets: The Transformation of Gangs and Violence on Chicago’s South Side” (Columbia University Press, 2020).

Alicia Hume saw her drug possession case dropped because of a new Oregon law — the first in the nation — making possession of small amounts of drugs the equivalent of a minor traffic infraction. Joe Kline / Sun-Times

“Why would I stand on the street corner and expose myself to police and my opposition and the elements if I can just work off of a phone?” Aspholm said. “That’s the transition of the South Side.”

On the West Side, people of all walks of life drive or walk up to the outdoor drug markets. The Eisenhower Expressway and the Blue Line and Green Line trains provide easy access.

In West Garfield Park, people who use heroin — many of them middle-aged and worn-out — trudge along Pulaski Road, crossing empty lots and approaching huddles of men who “sling dope” in the side streets and alleys.

This corridor of the West Side is not only a heroin marketplace, it’s also extremely violent. On just one block in West Garfield Park, five people were arrested on drug charges over the past year, five people were shot, and seven were charged with carrying guns.

Last year, the 11th police district, which includes West Garfield Park, had more killings than many cities. In 2020, for instance, there were 82 killings in the entire city of Minneapolis, compared with 99 in the 11th district.

The Cook County branch court at Kedzie and Harrison avenues, where most of the West Side’s drug possession cases are heard. Pat Nabong / Sun-Times

‘Officer, it’s not you. It’s just a low amount’

The low-level drug possession cases from the West Side are handled in Cook County’s felony branch court next to the 11th district police station. Most of the cases get thrown out. Defendants are often seen leaving the courthouse with smiles on their faces, some pumping their fists in victory and some skipping out of the door.

“People shuffle up, the case is dismissed, and they sprint out,” said one judge, who asked not to be named. “That’s what I would do. Before someone changes their mind.”

Judges and prosecutors say they’re reluctant to clog courtrooms and jails with people caught carrying a thimble-full of heroin or cocaine.

Nick Roti, a former chief of the organized crime bureau of the Chicago Police Department, remembers being a street cop and judges explaining why his drug cases were being dismissed: “They’d say, ‘Officer, it’s not you. It’s just a low amount. Don’t worry.’ ”

Often, officers show up in court only to watch their cases disappear before they’re even called to explain the arrest. Lots of preliminary hearings for drug possession are wrapped up in less than a minute. The defendant’s name is called, he or she walks up, and the case is dismissed.

Retired Illinois Appellate Judge Gino DiVito. AP

‘It would have taxed our abilities’

Prosecutors decide whether to charge someone with felonies like murders and rapes. But drug charges have always been excluded from that felony review process, in part because prosecutors would have to look at thousands of cases a year. So police officers typically decide whether to charge people with drug possession.

Gino DiVito, a retired Illinois appellate judge who helped create felony review in 1972 when he was a prosecutor, said the decision was left to the cops because there was a mountain of drug possession cases every year.

“It would have taxed our abilities,” DiVito said.

Another reason: They’re the simplest felony cases. Unlike murder cases, drug possession arrests often hinge on the word of the officer. They typically don’t require a confession or witness testimony.

Some defense attorneys say that gives cops too much latitude to stop and search people for drugs.

In their reports, officers often cite “suspicious behavior” in a known drug area as the reason for stopping someone, according to a review of hundreds of arrest reports.

That can mean two people talking outside an Uptown L stop. Or, in Raymond Galloway’s case, chatting with a woman on the street and walking away when he sees a cop.

Arrest reports contain head-scratchers like this one: An officer stopped a woman in Austin in 2015 after she walked through a vegetable garden in the winter. The officer wrote the woman’s actions were “nonamenable to gardening” because snow was on the ground. She was arrested for possession of 0.3 of a gram of heroin. Her case was tossed out.

The steep cost of drug arrests

Kathie Kane-Willis, policy director for the Chicago Urban League. Twitter

It’s expensive to lock someone up — even briefly — for having small amounts of drugs.

Kathie Kane-Willis, the Chicago Urban League’s research and policy director, once calculated the cost of jailing people whose drug charges were tossed out. In 2008, while she was an instructor at Roosevelt University, Kane-Willis studied 10 weeks of drug arrests at one Cook County branch court.

More than half of the possession cases for drug amounts under 15 grams were dismissed. About 75% of those cases involved half a gram or less of a controlled substance. During the study, about 100 defendants’ cases were dismissed, costing Cook County about $350,000. That included court costs and the cost of jailing those people, the study found.

The BGA and Sun-Times found more than $100 million was spent on briefly housing people in the Cook County Jail on low-level drug possession charges between 2013 and 2018. That figure includes the jail’s payroll and other basic incarceration costs but not medical care.

It’s a small fraction of the jail’s total budget over that period, but Kane-Willis said the money would be better spent helping drug users with their health and housing problems.

“I’ve spent two weeks in jail, kicking dope rather than going to my methadone treatment appointment,” said Kane-Willis, a former heroin user. “Is that a better system?”

Image

Nick Roti. Sun-Times file

Nick Roti. Sun-Times file

‘A chronic disease’

The Chicago Police Department didn’t respond to requests for comment about officers making low-level drug arrests. But Roti, the former police supervisor, said some low-level drug arrests serve a purpose.

Roti said gang members who run West Side drug markets entrust hand-to-hand sales to “buffers,” people who aren’t in a gang but sell small amounts of heroin to pay for their addiction.

When buffers are arrested for drug possession, they can give up information that helps build cases against violent gang members on some of the most dangerous streets in the city, he said.

Roti said the number of buffers who get arrested by narcotics officers is fairly small. A lot more people who use drugs get arrested as a result of patrol officers responding to complaints from aldermen and residents about drug activity, he said.

Roti said weaker drug laws — like one being contemplated in Illinois that would make possession of three grams of heroin or less a misdemeanor — would benefit drug dealers and make it harder for officers to tackle citizen complaints about drug dealing.

The Chicago police get tens of thousands of such complaints every year.

“How do you answer those calls for service?” Roti said. “Write a couple of tickets and drive away? More people come up, they sell more drugs. People don’t want to live like that.

A man caught with a small baggie of heroin is taken into custody by Chicago police officers in the 3600 block of West Flournoy Avenue in 2018. He was offered the chance of going into drug treatment instead of jail. Frank Main / Sun-Times

“No person with a substance-abuse disorder walks around with three grams of opioids in their pocket.”

Three grams of heroin is equivalent to 30 “dime bags” sold on the street, Roti said.

Still, like others in law enforcement, Roti said drug addiction is ultimately a health problem.

“They say, ‘The war on drugs’ — they love to throw that around — they make it sound like it’s a war against addicts,” he said. “I’ve never seen a war on drug addicts. I think people need to look at this more like a chronic disease.”

Keeping people out of jail for drugs

Roti spearheaded a Chicago Police Department program that connects arrested people to treatment. The program is for people arrested with less than one gram of cocaine or heroin. They aren’t charged with a crime if they agree to meet with a counselor. But they’re barred if they’ve been charged with selling drugs or have convictions for violent crimes or gun possession.

Participants are in their late 40s, on average, and are typically unemployed, according to the University of Chicago Crime Lab, which is monitoring the program. Since the program started in 2016, police have referred more than 800 people to drug treatment. Some weren’t arrested but walked in to a police station for help.

In a sample of about 50 people in the program, 31% stayed in treatment longer than three months. The program — the largest of its kind in the country — operates in half of the city’s police districts and is expected to expand to all of them.

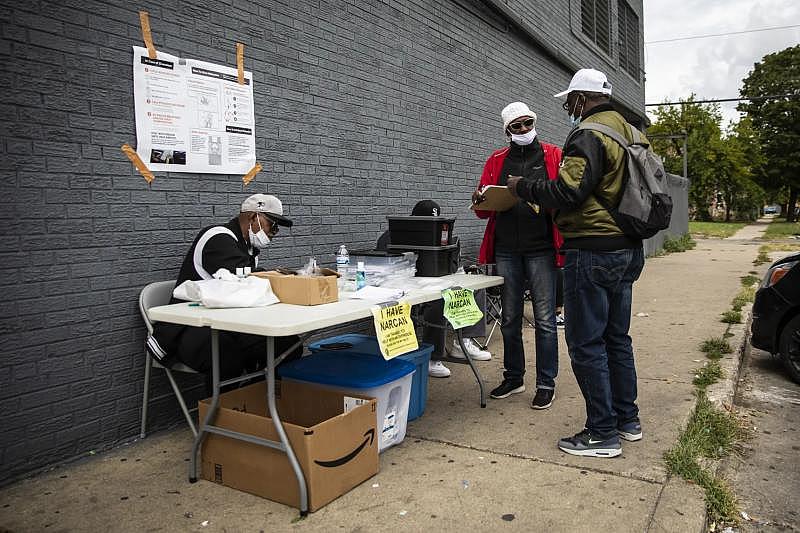

Gail Richardson (center, in red), an outreach worker for the West Side Heroin/Opioid Task Force, provides a man with overdose-reversal drugs including Narcan nasal spray and injectable naloxone along with a syringe. The outreach workers had set up a table near Roosevelt Road and South Albany Avenue on the West Side. Ashlee Rezin / Sun-Times

Addiction experts say keeping people who use drugs out of jail can save their lives. That’s because their tolerance for heroin diminishes in jail. They can risk overdosing if they return to their old habits when they’re out.

Since 2017, Cook County Jail detainees have been asked whether they use drugs, and they get treatment to minimize withdrawals, said Matthew Walberg, a spokesman for Cook County Sheriff Tom Dart. Methadone, Suboxone and Vivitrol have been given to detainees to treat opioid addictions, he said.

Detainees also are handed doses of the overdose-reversal drug naloxone when they exit the jail in case they relapse, Walberg said. More than 18,000 kits containing two doses have been distributed, he said.

“We’ve had some people who were given the naloxone within 40 minutes of leaving,” he said.

A card table on a sidewalk

In addition to the diversion programs, community outreach groups are going straight to the heroin markets on the West Side to offer help.

Elizabeth Elamri, who lives on the Southwest Side, showed up at a West Side Heroin/Opioid Task Force street outreach event to get overdose-reversal drugs. Ashlee Rezin / Sun-Times

Thresholds and the West Side Heroin/Opioid Task Force send outreach workers to meet people on sidewalks and street corners. They provide naloxone, clean needles and syringes. They can arrange for them to get methadone treatment if they want to kick their drug habits. They also help people apply for government IDs.

On a chilly morning in late September, Elizabeth Elamri and her friend Rafi walked up to outreach workers sitting at a card table on a sidewalk near Roosevelt Road and Albany Avenue. They walked away with overdose-reversal supplies. Then, they went down the street and scored some heroin.

Elamri, 56, said she’s had two friends die of overdoses. Rafi said his wife once revived him with naloxone.

“They’re saving lives here,” he said of the outreach workers.

Gail Richardson, who said she used to take heroin and was convicted of dealing drugs, is one of those workers.

“I have sat here and cried,” said Richardson, who works for the West Side Heroin/Opioid Task Force.

Rochelle Wade, with the drug addiction recovery agency Thresholds, shows a man how to use naloxone to reverse a heroin overdose. Ashlee Rezin / Sun-Times

“That once was me,” she said of a man who walked up for help. “When you get up in the morning, heroin is your breakfast and coffee.”

Tim Devitt, Thresholds’ vice president of clinical operations, said even more street outreach is needed. A change in the way drug treatment is defined by the state could help thousands of people, Devitt said. The state will pay for drug treatment that’s performed in a building, but the streets are where most of the need is, he said.

“It’s important to expand that definition to include support and services that happen outside four walls that can include outreach,” Devitt said.

People who use drugs need help with housing, jobs and forming relationships with other people, according to Devitt, who’s excited about the passage of the state’s Housing is Recovery law, which will provide rental subsidies to people at risk of dying of overdoses.

‘No great revolution’

Ben Ruddell, director of criminal justice policy for the American Civil Liberties Union of Illinois. Provided

Ruddell, the civil rights lawyer, is pushing for Illinois to pass a law to reduce low-level narcotics possession offenses from felonies to misdemeanors. Low-level narcotics possession is a felony in Illinois and 26 other states.

“This is no great revolution,” Ruddell said.

He noted that, in 2014, then-Mayor Rahm Emanuel and police Supt. Garry McCarthy told legislators they supported making possession of less than one gram of a controlled substance a misdemeanor.

Ruddell is an architect of a recent bill that would go even further, making possession of under three grams of heroin or methamphetamine and under five grams of cocaine a misdemeanor.

The bill stalled in the spring session of the Illinois Senate after winning House approval. Police associations opposed the measure. The leader of the Illinois Sheriffs’ Association said the bill wrongly reduced the penalties for what he considered to be large amounts of drugs.

And downstate lawmakers said the bill would make drug problems worse in their communities.

In Chicago, the mayor’s office and police department didn’t make any public statements about the legislation. The Cook County sheriff’s office didn’t take a position.

But the bill got support from the Cook County state’s attorney’s office and the Lake County and Champaign County sheriffs.

“People dealing with addiction need their safety net of support strengthened, not taken from them through incarceration,” Lake County Sheriff John Idleburg said in a letter to the Illinois House Judiciary Criminal Committee chairman. “Unfortunately, this is exactly what stiff criminal penalties associated with lower-level drug possession offenses do for people stuck in a destructive cycle of addiction and drug use.”

Lynn Boswell, a recovery coach with Thresholds, gets a hug from Elizabeth Elamri. Ashlee Rezin / Sun-Times

The bill isn’t dead, but it’s on a back burner, according to sources in the General Assembly.

Ruddell said the legislation would be a big step toward changing the way Chicago and other cities deal with people who use drugs.

“They’re still locking people up, and it’s still primarily Black people from low-income neighborhoods that we’re doing this to and sending them to prisons or jails,” Ruddell said. “Those are people whose employment and housing are being set back because of felony records. We need to focus on connecting people with access to services in their communities.

“Treating low-level drug possession as a felony isn’t working. It’s not reducing the use of drugs, the availability of drugs or the deadly overdoses.”

If you don’t see a survey form above and are interested in filling it out, please click here.

Frank Main is a reporter for the Chicago Sun-Times. Casey Toner and Jared Rutecki are reporters for the Better Government Association. This story uses data from The Circuit, an Injustice Watch and BGA courts data project, in partnership with civic tech consulting firm DataMade. The University of Southern California’s Annenberg Center for Health Journalism provided support for the project through a 2021 National Fellowship.

[This article was originally published by Chicago Sun-Times and Better Government Association.]