Coronavirus Files: State policies and social forces influenced death rates

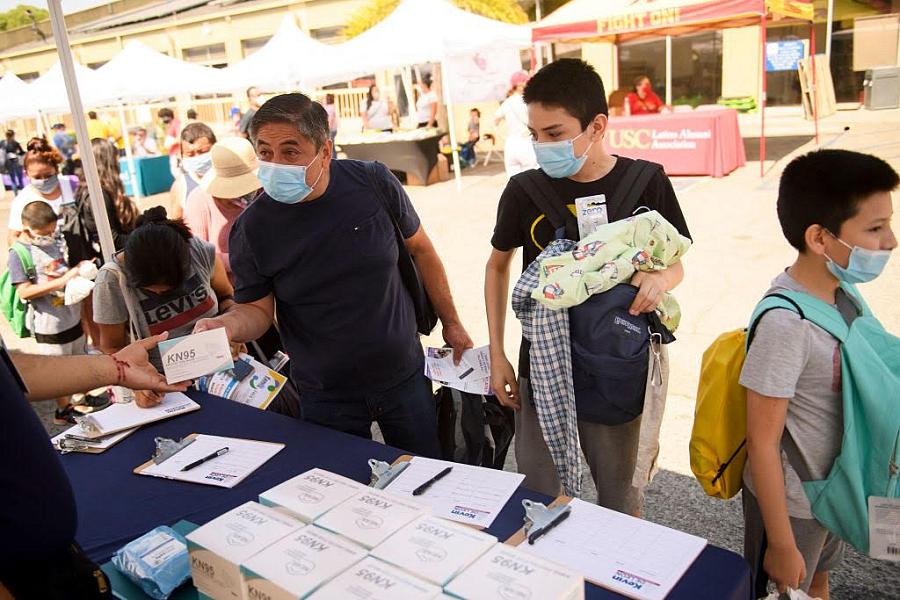

Families receive masks and other resources at a Los Angeles back-to-school event in 2021

Photo by Patrick T. Fallon/AFP via Getty Images

Pandemic lessons may improve long-term health equity

Hard-won achievements against the COVID pandemic and mpox outbreak may help public health officials combat inequities going forward, write Margo Snipe and Kenya Hunter at Capital B.

The pair describe how partnerships with community organizations narrowed the racial gap in vaccination rates in Boston, San Francisco, and Atlanta.

For example, the Boston team deployed health ad campaigns in up to 11 languages, including Spanish and Haitian Creole.

They also ensured that workers at COVID vaccine sites looked like members of the Black communities they wanted to reach.

Officials hope to continue and expand these efforts to counter other health issues, such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease, among underserved populations.

“We’re not just thinking about vaccination, but also thinking about ongoing access to testing, access to influenza vaccination, and really providing comprehensive services,” said Dr. Bisola Ojikutu, executive director of Boston’s health commission.

“Instead of pulling back, we have continued to move forward.”

COVID death rates varied by state

Hawaii saw 147 deaths from COVID per 100,000 people during the pandemic, the lowest rate in the U.S.

Contrast that with Arizona’s 581 deaths per 100,000, the highest rate in the nation.

A new paper in The Lancet delves into the social and political factors that might underlie the nearly fourfold difference across states, using data covering 2020 through mid-2022.

“Death rates in the hardest-hit U.S. states resembled those of countries with no health care infrastructure whatever,” writes Melissa Healy at the Los Angeles Times

The authors found that a lower poverty rate and higher levels of education were linked to lower infection and death rates.

Larger populations of Black or Hispanic individuals were tied to higher death rates.

Vaccine mandates for state employees, mask use and high vaccine uptake were also associated with better COVID outcomes.

High levels of trust of other people, which led to willingness to protect others, was also linked to lower death rates.

“How we feel about one another matters,” said study author and political scientist Thomas J. Bollyke. “The solidarity between people — the feeling that others will also do the right thing, that you’re not being taken advantage of — is a big driver in your willingness to adopt protective behaviors.”

That kind of trust has been declining in the U.S. since the late 20th century, Bollyke added.

In addition, trust in the government has dropped among Black Americans and Republicans during Biden’s tenure, according to a 2022 Pew Research Center report.

A high proportion of Trump voters was also linked to a higher death rate.

“The COVID-19 pandemic clearly exacerbated fundamental social and economic inequities, but science-based interventions and policy changes provided clear impact on mortality rates at the state level,” said ABC News contributor Dr. John Brownstein.

Will we get a spring boost?

The FDA is mulling an additional round of bivalent boosters, possibly for people older than 65 and immunocompromised individuals, reports Rob Stein at NPR.

“Those doses are going to be expiring and will be thrown out,” said Dr. Peter Hotez of the Texas Children’s Hospital for Vaccine Development. “It makes sense to have those shots in arms instead of being tossed.”

A spring booster could address waning immunity in those who got their fall boosters but remain at risk for severe disease or death.

It’s likely that protection from the bivalent vaccine wanes within months, as occurred with the original-formula shot, and that an additional vaccination would boost protection, writes Dr. Leana S. Wen at The Washington Post.

“The benefit might be negligible for healthy young people,” writes Wen. But she argues that a booster would be an appropriate option for immunocompromised people and older individuals who want to maximize their protection.

Last week, the World Health Organization issued its new guidelines on vaccination.

The WHO suggested that an additional booster should be available after six or 12 months for older adults, younger adults with conditions such as diabetes, adults and children who are immunocompromised, pregnant people, and frontline health workers.

It said that healthy adults, up to age 50–60, can stop after their first booster.

And the WHO no longer specifically recommends COVID vaccination for children and teens.

The WHO noted that countries should base their individual approaches on their own disease burden and health spending, and that these guidelines only apply to the current COVID situation.

In the U.S., the CDC still recommends that everyone ages six months and older get up to date with COVID vaccines, which includes the bivalent booster for nearly everyone.

The difference between CDC and WHO advice could further confuse the public, microbiologist Stanley Perlman told Bloomberg’s Karen Leigh and Tanaz Meghjani.

COVID’s effect on the brain grows clearer

There may be two categories of long COVID’s effects on the brain, reports Judy George at MedPage Today.

Researchers found that people who were sick enough to require hospitalization during their initial bout with COVID were most likely to suffer problems with attention, working memory and processing speed.

In contrast, those whose initial infection was milder tended toward brain fog, headaches, dizziness, and loss of smell and taste.

The different groups may require different treatments, said Dr. Ziyad Al-Aly of the Washington University in St. Louis, who wasn’t involved in the research.

Researchers have also strengthened the neurologic link between long COVID and myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME), commonly known as chronic fatigue syndrome, another condition that can occur post-infection.

In a small brain imaging study, scientists found similarities between long COVID and ME patients, in that both showed an enlarged brainstem, reports Carly Casella at Science Alert.

The brainstem controls brain function as well as respiration, heart function, and digestion.

Its increased size could reflect the presence of a virus, inflammation and swelling, or degeneration of the nerves, according to the study authors.

COVID exposure in pregnant people has also been linked to neurodevelopmental disorders, such as intellectual disabilities or movement disorders, in the boys they deliver (but not girls), reports Nina Cosdon at Contagion Live.

From the Center for Health Journalism

National Fellowship Applications Now Open

The 2023 Fellowship will provide $2,000 to $10,000 reporting grants, five months of mentoring from a veteran journalist, and a week of intensive training at USC Anenberg in Los Angeles from July 16–20.

Click here for more information and application form, due May 5.

What we’re reading

- “Women were already unequal in the world of global health. The pandemic made it worse,” by Melody Schreiber, NPR’s Goats and Soda

- “COVID’s education crisis: A lost generation?” by Tracy Smith, CBS News

- “‘Being truthful is essential’: scientist who stumbled upon Wuhan COVID data speaks out,” by Michael Safi and Eli Block, The Guardian

- “Trans health care, already under attack, faces new obstacle with end of COVID public health emergency,” by Theresa Gaffney, STAT

- “AstraZeneca’s COVID vaccine may have posed a higher heart risk for young women, study shows,” by Apoorva Mandavilli, The New York Times

- “A new flu is spilling over from cows to people in the U.S. How worried should we be?” by Michaeleen Doucleff, NPR Morning Edition

- “Cases of a drug-resistant fungus tripled during the COVID pandemic,” by Philip Kiefer, Scientific American

Events & Resources

- April 24, 2023, 8–9 a.m. PT: The Scientist hosts a live symposium, “What Could Cause the Next Pandemic?”

- There are still several COVID trackers that are posting data, and the COVID-19 Data Dispatch has a list.

- Access pandemic-related reports from the National Academies on their COVID-19 landing page.