A catastrophic flood on California’s Central Coast has plunged already marginalized Indigenous farmworkers into crisis

This project was originally published in Inside Climate News with support from our 2023 Health Equity Impact Fund

The disastrous Pajaro flood made the home Emilio Vasquez rents with his family unlivable. He's still waiting to hear when he can move back in.

Liza Gross

PAJARO, Calif.— It was half past midnight on March 11 when a cacophony of sirens and shouting jolted Emilio Vasquez and his family from a sound sleep. “Get out of your houses immediately!” a voice barked in Spanish through a bullhorn. “The water is coming!”

Vasquez and his wife, undocumented Indigenous Mexican immigrants who speak Mixteco, understood just enough Spanish to bolt out of bed, grab their two young children and race to their car. They headed south out of town, wondering why water was threatening their rental in Pajaro, an impoverished, unincorporated farmworker community, about 95 miles south of San Francisco, that helps power Monterey County’s $4 billion agriculture industry.

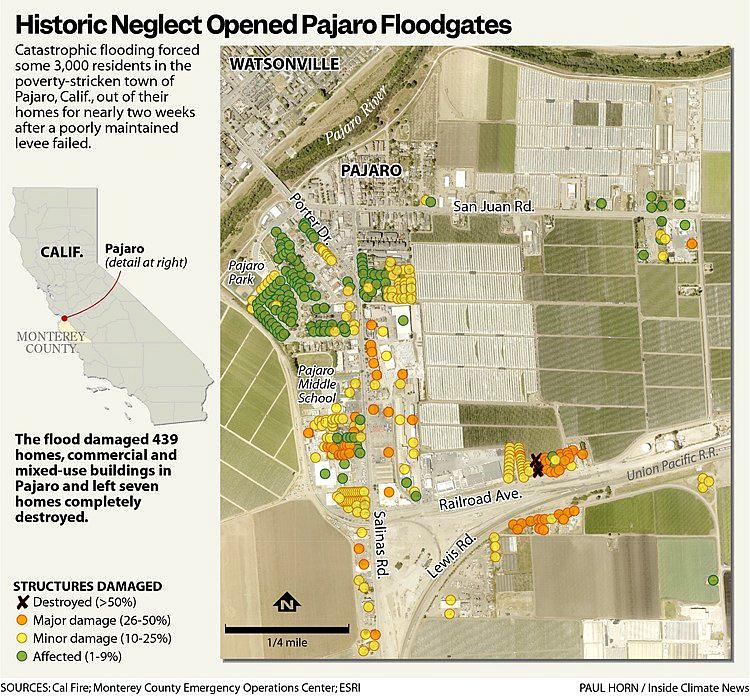

Vasquez, who asked not to use his real name for fear of retaliation, did not learn until the next morning that the storm-swollen Pajaro River—which forms the border between Monterey and Santa Cruz County to the north—had demolished a section of the levee on its long-neglected southern side. The levee’s deficiency was clear soon after it was built in 1949. It failed twice in the fifties, prompting Congress to authorize millions to fix it, then again several times in the 1990s, when a catastrophic flood killed two.

The poorly maintained levee proved no match for a waterway transformed by winter’s relentless succession of monsoon-like atmospheric rivers. The breach sent a tidal wave of mud and water through Pajaro, stranding cars, damaging hundreds of homes and small businesses and forcing the town’s 3,000-some residents to evacuate, just as it had nearly to the day, in 1995.

Paul Horn / Inside Climate News

The March floods inundated more than 8,700 acres of cropland worth $264 million, according to the Monterey County Agricultural Commissioner’s Office, bringing total damages from winter storms to $600 million.

How many farmworkers’ jobs were washed away with the crops is unknown.

Workers were already struggling to feed their families, as farmers had fallowed fields during California’s multi-year extreme drought. Now, a warming planet was making farm work, already among the nation’s most dangerous occupations, even more hazardous.

Climate change is increasing the risk and extent of wildfires, the frequency and severity of heat waves, the intensity of atmospheric rivers and the likelihood of devastating floods.

That places workers like Vasquez, who get paid based on how many fruit or vegetable boxes they pick, in greater danger as they move through fields as fast as they can, even when nearby wildfires release clouds of toxic smoke or soaring temperatures increase their risk of heat stroke or death.

Vasquez, clean-shaven with a slight but muscular build and straight black hair, stands with remarkably erect posture for someone who’s spent years bent over picking berries. Now, that grueling work is the least of his concerns.

Vasquez and other Indigenous farmworkers are finding themselves at the mercy of cascading climate disasters, bouncing from one hellscape to another like characters in a dystopian climate novel. But the catastrophic flood has made the devastating toll these disasters take on their lives and livelihoods all too real, with no relief in sight.

Migrants dispossessed by decades-old free-trade agreements in the mountains of Mexico risked their lives to eke out a better living picking strawberries for dollars a day only to become dispossessed by climate change. They played no role in global economic policy or the climate crisis yet are reeling from the repercussions of both. Robbed of the means to make a living at home, they now struggle to survive life-threatening floods, heatwaves and wildfires without a safety net in one of the richest countries in the world. The federal government, which relies on the cheap labor of unauthorized workers to keep food prices low, has done almost nothing to help them, leaving a state saddled with a budget deficit and under-resourced local governments and nonprofits scrambling to do what they can.

Workers pick strawberries in a field unaffected by flooding near Aromas, southeast of Pajaro, on the north side of the Pajaro River.

Liza Gross

About three-quarters of California’s roughly 800,000 farmworkers, including most Indigenous farmworkers like Vasquez, are undocumented. They lack access to healthcare, unemployment, loans and other resources that help authorized workers get through a disaster. Most live in daily fear of deportation, making them more likely to accept subpar wages, working and housing conditions rather than risk getting fired or deported. Many speak little English or Spanish, limiting their ability to understand emergency warnings or access recovery aid.

And fear of La Migra, the immigration police, can lead to paranoia and isolation during an emergency when language barriers make it difficult to know what’s happening, an early study of Indigenous farmworkers found.

Although farmworkers were deemed essential at the start of the coronavirus pandemic, their immigration status severely limits their resilience during a crisis.

“What we are seeing with Indigenous language speakers with this disaster is that they are being disproportionately negatively affected,” said Nancy Faulstich, executive director of the nonprofit Regeneración Pajaro Valley Climate Action.

“The community hasn’t had the time or resources to advocate for itself,” she said. Even if they did, she added, most don’t want to attract public attention, worried they would face repercussions for being undocumented.

Climate change-fueled disasters compound the environmental racism that created infrastructure and resource deserts in communities like Pajaro, said Michael Méndez, assistant professor of urban planning and policy at the University of California, Irvine.

“It shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone when an extreme storm event, a heatwave, a wildfire or drought hits, that these communities with crumbling infrastructure and historic disinvestment are hardest hit,” Méndez said.

Migrating Out of Necessity, Not Choice

About 170,000 Indigenous migrants live in California, according to the Mixteco Indigena Community Organizing Project, with nearly half living on the Central Coast, from Oxnard near Los Angeles to Watsonville south of San Francisco. Ninety-two percent of Pajaro’s residents are Mexican and about a third speak little or no English, according to U.S. Census data. But the agency has scant data on those who speak primarily Indigenous languages in Pajaro or anywhere else.

Vazquez was in his mid-twenties when he left his Mixtec community in San Martín Peras in 2017, the same year then-President Trump ramped up efforts to detain and deport undocumented immigrants. The discrimination heaped on Vasquez and his village peers for their bronze-colored skin and small stature followed Mixtec migrants across the border. Yet for Vasquez, a deeply private man who refuses to have his picture taken to protect his family, those shared traits serve a determination to blend in among Indigenous Mexican expats and escape U.S. immigration authorities’ notice.

President Biden has taken steps to expedite legal pathways for migrants. But the unremitting fear of detention, deportation and family separation has taken a psychological toll on many undocumented workers, whose distrust of institutions prevents them from seeking help. That fear is compounded by an often traumatic border crossing, persistent language barriers and, now, climate change.

Vasquez, whose wary hypervigilance seems to have etched permanent worry lines across his young brow, did not want to talk about his immigration status or journey across the border. A gentle but serious man, he allows only the occasional smile, as if to acknowledge the absurdity of having so little control over his fate. All he would say, shifting in his chair, dark eyes downcast, was he came straight to Watsonville, following two brothers who live in the area.

Vasquez and his wife, who let her husband do most of the talking, left their hometown because there were no jobs. “There is no money to buy food, shoes, clothes, basically everything that we need,” he said through a Mixtec interpreter in a community center in Watsonville, as his nine-year-old son and chipper two-year-old daughter played in an enclosed courtyard a few feet away.

Schoolwork from one of Emilio Vasquez’s children still hangs on the wall of the home he rents with his family after the devastating Pajaro flood made it unlivable. The family is still waiting to hear when they can move back in.

Liza Gross

Many farmworkers in Pajaro who were displaced by the flood were first displaced in Mexico by free-market policies that upended their way of life.

The 1993 North American Free Trade Agreement drove prices for corn and other crops so low that small farmers couldn’t afford to grow them. Mexico eliminated farm subsidies around the same time. Indigenous communities could no longer depend on subsistence production and cash crops to support themselves.

The poverty rate for Indigenous populations in Mexico is now nearly double that for non-Indigenous people. They are among Mexico’s most marginalized populations, a legacy of Spanish colonial practices that devastated native cultures, societies and economies as well as modern-day discrimination leading to lower education levels, fewer job opportunities and limited access to healthcare and credit.

Migrants hoping to leave the trappings of poverty and discrimination behind when they come to the United States instead find the same forces at work, made even worse by lack of citizenship status and federal carveouts for farmworkers. U.S. law has excluded farmworkers from federal labor protections starting with the 1935 National Labor Relations Act, ostensibly to protect crops from a strike at harvest.

Indigenous Mexicans, now the fastest-growing segment of California farmworkers, are more likely to occupy the bottom tier of the farm labor market, performing more arduous, lower-paying tasks, like picking strawberries. When workers receive higher wages, a study of Indigenous farmworkers found, it’s likely to be because they worked faster, under poorer conditions on a piece-rate basis. Even then, most make only about $85 to $100 a day, which has to support their families during the months-long off season.

Many end up living in historically neglected towns like Pajaro.

There’s nothing natural about the way a natural disaster affects communities like Pajaro, said Méndez. Policy decisions and political choices intentionally withheld vital resources in infrastructure, funding and disaster preparedness from the most marginalized and stigmatized communities, like those with undocumented migrants and farmworkers, he said.

For weeks after the floodwaters receded in Pajaro, towering mounds of fetid, mud-caked debris lined nearly every street. Appliances and furnishings that took years of savings to buy—sofas, mattresses, refrigerators, stoves—lay in ruins alongside children’s bikes, stuffed animals, family photos and other cherished possessions.

Undocumented workers already knew the fear of having their lives destroyed in an instant by La Migra, which they fear could show up at any time after a grueling day in the fields. And though the literal debris has been cleaned up, the disaster has only exacerbated the precariousness of living in the shadows, without a safety net.

Vasquez didn’t know how U.S. immigration policy penalizes undocumented workers when he left his remote village in Oaxaca. He knew nothing of Pajaro’s flood risk or that government plans to protect it had languished for decades when he rushed his family out of the house that scary March night. He had no idea his life would be turned upside down when he joined the throngs of rattled evacuees on the two roads out of town.

Vasquez drove his family about 20 minutes south to stay with his brother in the Salinas Valley. When he woke up the next day, he learned that the whole town of Pajaro was underwater. Standing water, mud, mold and debris had ruined hundreds of buildings, including the house his family rented.

In the rush to escape the advancing water, Vasquez had no time to gather his family’s belongings. “We lost everything,” he said, his voice trailing off.

Essential but Illegal

In February 1998, a series of El Niño storms pushed warm water toward the West Coast, causing intense flooding in Monterey County and forcing the entire town of Pajaro to evacuate. Twenty-three years later, the Pajaro Regional Flood Management Agency was formed by the city of Watsonville, Santa Cruz and Monterey counties and water agencies to reduce flood risk in the region. Before the latest flood disaster, the $400 million project to shore up flood protection for Pajaro and Watsonville was slated to break ground in 2025. Now, officials plan to start construction next summer.

The level of need in Pajaro overwhelmed local governments, which scrambled to help cash-strapped residents. Monterey County ran an emergency shelter at the Santa Cruz County Fairgrounds in Watsonville, which at its peak housed more than 500 people with nowhere else to go. The county closed the shelter in mid-May, and offered a limited number of hotel vouchers through a program slated to end July 30.

Agricultural fields remain waterlogged around Pajaro, California several weeks after the storms that drove the flooding in the region.

Liza Gross

Fields that would normally be full of strawberries in spring were bare after the flooding that devastated Pajaro, California in March, 2023.

Liza Gross

Monterey County spokesperson Nicholas Pasculli said fewer than 30 people are living in hotels now. He’s confident anyone still in need of housing will find it before the program closes. “We’re not walking away from folks,” he said.

The county provides services to all residents regardless of immigration status, Pasculli said. There was “a herculean effort” to let Pajaro residents know about available resources, he said, led by the county’s community-based organization partners.

Yet nonprofits that serve immigrants are not equipped for disaster aid, said Méndez. They were stretched thin from Covid, he said, and now these under-resourced organizations are being asked to do all this additional work with little funding.

As a result, many, including Vasquez, never heard about the shelter or hotel program.

“We just got out of the house and we’re just roaming around,” Vasquez said matter of factly, hands folded on his jeans. “We haven’t done anything when it comes to researching for resources because we don’t speak very good Spanish. The language barrier is big and we really don’t know where to ask for help.”

When federal officials declared farm laborers “essential workers” near the start of the pandemic, they extended only limited health and safety benefits to undocumented workers. As a result, agricultural workers had the second-highest Covid-19 death rate in California, with noncitizen immigrants at highest risk.

These workers still cannot access federal unemployment insurance and disaster assistance, among other benefits critical to economic stability.

More than 2,000 Monterey County residents registered for disaster relief from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA, which has approved close to $4 million in aid so far, Pasculli said. The agency provides only county-level data, so it’s unclear how much went to Pajaro residents.

Unauthorized immigrants are eligible for FEMA only if a child or other household member is a citizen. A friend told Vasquez, whose daughter was born in the States, that he could apply for aid at Pajaro Park, where FEMA had set up a recovery center. He went to the park to see if he could get help to pay for a hotel room in early May. Someone entered his information on a computer and assured him he’d hear back in two days. “We never got a call,” he said, clearly frustrated, but without a hint of anger in his voice.

He’s struggling to make ends meet in Monterey County, where the cost of living is 37 percent higher than the national average. “We live in one of the most expensive counties in the country,” said Eloy Ortiz, special projects manager for Regeneración Pajaro Valley Climate Action. “And agricultural workers are among the lowest paid for the hardest work.”

Farmworker wages average $35,200 in Monterey County, based on Bureau of Labor Statistics data. But these surveys likely miss many undocumented workers, who are often paid less and, like many farmworkers, vulnerable to wage theft. Vasquez said he and his wife each make only about $21,000 a year picking strawberries—when there’s full-time work during the season.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom promised to mobilize funds for undocumented workers in March, after touring Pajaro. Finally, in June, the state Department of Social Services announced it would distribute $95 million for people who can’t access federal relief. So far, $6.2 million has been allocated to Monterey County and $5.1 million to Santa Cruz through the Storm Assistance for Immigrants Project, according to a department spokesperson.

“Frankly, I am very frustrated by hearing all of this supposed good news coming through, when on the ground, I’m not seeing any of it,” said Ann López, executive director of the nonprofit Center for Farmworker Families. “We still have farmworkers calling all the time begging for Target gift cards so they can buy food, wondering if they’re going to be able to stay in the hotel.”

Ann López, executive director of the Center for Farmworker Families, speaks about the needs of Pajaro Valley’s farmworkers at the Unitarian Universalist Fellowship of Santa Cruz County in May.

Liza Gross

López said some 1,500 families need at least $25 million to get back on their feet. The region’s small farmers, she said, need another $5 million to stay in business and get their crews back to work.

Floodwaters ruined nearly 2,000 acres of strawberries, Monterey County’s top crop worth more than $968 million, and a major source of farmworker jobs.

The January storms destroyed seven acres of strawberries on Javier Zamora’s 200-acre organic farm, JSM Organics, a few miles south of Pajaro. The creek that runs along his fields rose four feet in early January, leaving his strawberries underwater for a month. Zamora, who is as passionate about sustainable farming as he is about his workers, estimates he lost $150,000.

It pained Zamora that he had no work for his farm hands for a month and a half. Zamora’s customers advanced him $87,000, which helped. “But as far as government money?” he said. “Zero yet.”

Javier Zamora, owner of JSM Organics, south of Pajaro, lost $150,000 worth of strawberries during January storms. Floodwaters quickly inundated seven acres of strawberries, he said.

Liza Gross

Vasquez and his wife couldn’t find work in the strawberry fields until mid-May. Even then, the young couple worked far fewer hours than normal.

But no one is tracking the flood’s impact on farmworker jobs.

The unemployment rate for the county was 6.3 percent in May compared to 4.7 percent last May, according to a recent California Employment Development Department analysis. But the rates are likely much higher for farmworkers, since the figures are derived partly from unemployment insurance claims—which unauthorized workers cannot file.

California just passed a budget earmarking $20 million to Monterey County to support people affected by the flood, regardless of immigration status. Yet distributing these funds is likely to take months of screening and possibly longer to reach Indigenous-speaking workers. By that time, workers may have left to find jobs elsewhere, advocates say.

“This is climate displacement and who’s being displaced in California are farmworkers,” said Faulstich. “People don’t have work and then they don’t have money to spend in the businesses, so small businesses are suffering.”

These climate change-induced shocks throw everything off, she said. “And we’re just so not prepared.”

Risking All for a Better Life

Elena Mendoza, a shy, soft-spoken mother of seven from a Mixtec village in southern Mexico, lives far enough north of the Pajaro River in Watsonville to have escaped flood damage. But like hundreds of other farmworkers in the region, she struggled to find work and pay her rent after the storms laid waste to thousands of acres of agricultural fields in the region.

Mendoza, who asked not to use her real name because she is undocumented, missed months of work, she said through a Mixtec interpreter. She’s worried if she falls too far behind on rent, she’ll lose the home she shares with her husband and children.

Many Indigenous farmworkers spent just a few years in primary school. Mendoza made it to sixth grade, yet it’s been overwhelming for her to figure out what aid she’s eligible for. The county and state offer resources in Mixteco on their websites, but neither Mendoza nor Vasquez knew that. A friend told Mendoza that local nonprofits distributed food and basic supplies each month to help families affected by the floods, which has been a big help.

But if Mendoza can’t pay the rent, she will have a very hard time finding a new place to live.

There is an urgent need for affordable farmworker housing in the Pajaro and Salinas valleys. Nearly 90 percent of the region’s 91,000 farmworkers live in exceptionally crowded conditions, with a quarter sleeping in a room with three or more people, a U.C. Merced Labor Center report found.

Though many farmers in the region reported facing a labor shortage in a 2018 study, most did not connect their trouble finding workers with the housing crisis. But the lack of safe, affordable housing is so acute, the county recently found more than 60 families, many Indigenous, paying up to $2,500 a month to live in converted greenhouses south of Pajaro that lacked ventilation, operable windows, heat, smoke detectors, proper plumbing, bathrooms or kitchens.

The county shut the rogue operation down. But such living conditions are common in the Pajaro Valley, farmworker advocates say.

Mendoza, a slight 35-year-old with a broad face and almond-shaped eyes that radiate warmth and optimism, didn’t know what to expect when she left her rural, mountainous Oaxacan village some 20 years ago in search of a better life.

She is from a different region of Oaxaca than the Vasquezes. But like most Indigenous Mexicans, she faced similar challenges. Her parents grew beans, squash and corn following ancient milpa companion planting practices designed to boost pollinator diversity, soil health and reap other ecological benefits. But her parents, like most people in her little town, grew just enough for their family. They had no money to buy other foods or basic necessities in a region where nearly 1 in 4 people live in extreme poverty.

Mendoza, clad in a gray sweatshirt emblazoned with the word California, was just a teenager when she left home, hoping she could find work in the States to help support her struggling parents. She didn’t know if she’d ever see her parents again. She just knew she had to try to help them, she said, nervously pulling her sweatshirt hood over her long, dark hair.

Mendoza and her brother caught a bus near their home in San Martín Peras and traveled three days to the desert town of Altar, a last stop for migrants hoping to reach the States. Her brother found a “coyote,” a guide who said he could smuggle them across the border, for $2,000 each, about $3,300 in today’s dollars. The coyote told them to buy as much food and water as they could carry.

They then walked for three nights, when temperatures dipped near freezing, and had no protection from the cold or the seemingly endless rain. They rested during the days, to escape notice. That’s when she saw the snakes. And realized, to her horror, that the hair and bones sticking out of the dusty dirt were someone’s remains.

Hundreds of people die each year trying to cross the border, desperate to find work. The vast majority are from Mexico.

Mendoza and her brother made it across somewhere in Arizona. She doesn’t know where. On the last day, the Border Patrol apprehended and deported them. They went back to Altar to try again. But her brother stayed behind, hobbled by badly blistered feet. Mendoza, scared but determined, found another coyote.

When she got to the border, the coyote directed her to a waiting van. It had dark windows and no seats, to cram in as many people as possible. Mendoza squeezed into the mass of bodies, hoping for the best.

This time, she made it.

Mendoza landed at a cousin’s in Oxnard, a major strawberry-growing region with a thriving Indigenous Mexican community, north of Los Angeles.

She looked for work in the strawberry fields but everyone told her she was too young. So she decided to try her luck in Salinas, which she heard also grew strawberries. She went to a field and asked the supervisor for a job. He told her to go to school. Desperate for money to pay for food and rent, she shadowed him all day, begging for work. Finally, he relented.

Now, 20 years later, she’s nearly as desperate for work.

Mendoza never tried to return to her village, unwilling to endure another border crossing. She now lives with the heartache of not seeing her mother before she died, four years ago.

Mendoza did not want to talk about her fear of La Migra, she said, her hand over her lips as if trying to trap the words. But she thinks the people who risk their lives to walk through the desert, hoping to find work to help their families back home, should be granted permission to work here. And she thinks that maybe when farmworkers can’t find work, the taxes she sees taken out of her paycheck could go to some sort of fund to help them get by.

Still Waiting for Relief

Vasquez and his family have not been able to return to their home since the flood made it uninhabitable. The family stayed with Vasquez’s brother in the Salinas Valley for a few days, then drove back north to stay with another brother, who lives in a one-bedroom apartment in Watsonville. Vasquez and his wife sleep in the living room, while their kids crowd into the bedroom with his brother.

Vasquez’s family can stay as long as they need to, as far as his brother is concerned. But the apartment manager forbids overnight visitors. “We can’t even allow our kids to cry,” Vasquez said. “If they cry, then we will have to find a way to distract them. Otherwise they’ll find out, and we’re afraid that they will kick us out.”

The disastrous Pajaro flood made the home Emilio Vasquez rents with his family unlivable. He’s still waiting to hear when he can move back in.

Liza Gross

So he and his family have been bouncing back and forth between his brothers’ homes for months, as he waits for his landlady, Evelia Martinez, to fix their one-bedroom.

Martinez, a mother of five, including a niece she calls her own, applied for FEMA aid to fix the Vasquezes’ house. But she discovered rental properties aren’t eligible. She finally got a loan, but reconstructing the walls and floors and replacing all the trashed furniture and appliances will take time.

Martinez, who volunteers at her nine-year-old son’s school, lost her own home in a rural area of Watsonville, after the storms knocked down power lines. Martinez, her husband and three of their kids are crowded into her sister’s house in downtown Watsonville.

A petite woman with curly brown hair, Martinez said she’s usually a positive person with a can-do attitude. “But when Pajaro flooded, it kind of just crushed me,” she said.

Dealing with her own displacement, the loss of the small income she got from her rental, and seeing the Vasquezes, “a great family,” left without a place to live was more than she could bear.

She relays as much information to Vasquez as she can in Spanish, unsure how much he understands. She felt terrible when he asked her if they could stay in a tool shed next to the house until the repairs were done and she had to tell them no. She just couldn’t let them live with their kids in a shack with no heat, windows or plumbing. Instead, Vasquez has been using it to store the few things he salvaged from cabinets above the water damage.

But as the months without his own place drag on, the stress of hiding from his brother’s landlord and La Migra weighs heavily on his mind. If he could, Vasquez said, he would ask political leaders to get him the help and support his family needs. And permits so he can work here legally. He thinks it’s only fair for all the hard work he and his wife do.

Meanwhile, farmworker advocates worry that another disaster could be around the corner, now that El Niño is officially here. The weather system heats up the Pacific Ocean, potentially bringing heavy rains.

The levee reconstruction won’t be finished for nine years, said Ortiz of Regeneración Pajaro Valley. “What’s the plan, if this happens again next year, or even two or three years from now?”

The agricultural industry depends on people from Pajaro and other marginalized towns to keep food prices low, Ortiz said. People have already left the region to find work or housing. “Without a safety net for people,” he said, “what’s going to happen if all the farmworkers move?”